Young people have a different perspective on the hardships of winter. During the legendary winter of 1949, Charlie Wright was sixteen years old and staying at his uncle’s farm northeast of Scottsbluff.

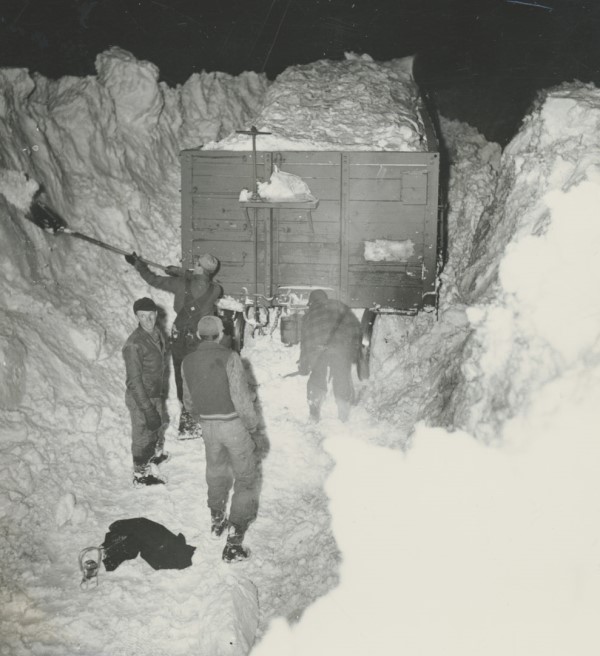

A locomotive pushes a snowplow near Kilgore (Cherry County), Nebraska, in January 1949. History Nebraska RG1259-0-15

By Charles E. Wright, Scottsbluff, Nebraska

Editor’s note: Young people have a different perspective on the hardships of winter. During the legendary winter of 1949, Charlie Wright was sixteen years old and staying at his uncle’s farm northeast of Scottsbluff. Wright went on to become a Scottsbluff attorney and was a longtime History Nebraska member. We’ve illustrated his story with some photos from our collection.

This is the way it was on Sunday, January 1, 1949. I was a sixteen-year-old junior who lived in Scottsbluff with my parents and a younger sister and brother. A spring-fed stream called Winter Creek ran for about one-half mile through the farm of my uncle, Martin L. Gable (who also served a term on the Game and Parks Commission). His farm was located seven miles northeast of Scottsbluff. Each morning during the holiday season I would run an assortment of thirty-six muskrat traps with my good friend (and trapping partner) Dick Mead. A prime muskrat pelt would bring two and a half to three dollars from the local hide and fur dealer, and we usually came up with two or three prime pelts each morning. With traps costing fifty cents and gasoline costing twenty cents a gallon, our profit margin was good. Out at dawn, it took about thirty minutes to run, move and reset the traps, and another hour or so to skin the muskrats and stretch their pelt over a shingle to dry. Muskrat fat had a peculiar odor, and I needed to scrub-up if we ran the traps on a school day. No one really wanted to sit next to me in class and my girl friend made me feel unwanted.

This Sunday morning Dick and I ran the traps on Winter Creek and decided to reset them in some new runs that we found on a small side creek. Dick (who had not been rejected by his girl) drove back to Scottsbluff while I phoned my parents and told them that Uncle Mart would drive me in to school Monday morning.

My two younger cousins, Marty and Johnny Gable, were good companions, and we planned to hunt rabbits with our .22s in the nearby hills that afternoon. Staying out at the farm was great fun. Aunt Doris would always let us make fudge or molasses taffy if we were hungry—which was all the time.

The morning radio report came out over Denver station KOA. First, Happy Jack Turner would sing “Good morning, good morning, a new day is dawning. A happy, good morning to you!” The weather report followed, predicting a clear day with possibly a little snow. Little did they know what was in store for all of us—they had filled up on that Colorado kool-aid and it had not worn off by Sunday morning.

Aunt Doris taught school in Lyman (a small town about thirty miles west of Scottsbluff which was famous for its Silver Glide Ballroom where the band played each dance tune three times in a row). Uncle Mart would drive her up to Lyman on Sunday afternoons, then return to referee the boys until she returned the following Friday. There was leftover mincemeat pie from Christmas and a half-eaten batch of liebkuchen to hold us until supper.

About two o’clock in the afternoon the wind came up out of the north, and it was spitting snow. By two-thirty it was snowing so hard that you could not see the power pole about twenty feet south of the house. The cousins were playing poker and paid little attention to the storm. About three PM Uncle Mart and Aunt Doris returned. They were unable to make it to Lyman and lacked confidence in our ability to ride out the storm, particularly if we lost the electric power that was necessary to operate the oil furnace. This was okay with us because Uncle Mart could teach us some more poker games—and perhaps give us a little pinch of the Copenhagen snuff that he slipped in between his lip and gum. It continued to snow, and the wind gusted up to one hundred miles per hour throughout the night and the following two days.

Handwritten on the reverse side: “Snow! Chadron, Neb Feb 1949.” History Nebraska RG3139-0-161

After breakfast the next morning Uncle Mart had to walk about one hundred yards to the cow shed to break ice and feed and milk four cows. On the way back to the house, he had to carry water and grain to the chicken house that was about twenty-five yards east of the home. The cousins and I bundled up, rigged lines out of binder twine to keep us close together, and went with him. It was difficult to see or even breathe while exposed to the direct force of the wind.

The storm continued for about two-and-a-half days, but our power and telephone lines held. The roads were all snowed shut with ten to fifteen-foot drifts, and the schools shut down for two weeks. We had some bacon, a few lamb chops, and some leftover ham from Christmas. There was plenty of flour and sugar, and almost ten pounds of potatoes, but this would get old and boring in a couple of days.

Located about two miles southwest of Lake Minatare, Winter Creek originates near the northeast corner of the farm. Mart’s farmhouse was about one quarter-mile west of it. The creek is full of holes, riffles, and overhanging banks, providing excellent habitat for the rainbow and brown trout that were stocked by the Game Commission. It is full of watercress in the fall, which the ducks loved to eat. The creek flows all year at a temperature of fifty-four degrees. It was surrounded by cornfields at its north end, and we could see large flocks of mallards flying back and forth from the cornfields to the creek. Despite the heavy snow cover, some of the ducks were able to find corn. In some places the wind and snow had created a solid bridge over the running water flowing southwest down the creek. The temperatures hovered around zero after the wind stopped blowing. It was, as they say, “colder than a dead witch’s toe.”

What to do for variety in our diet. Aunt Doris had an idea. The freezer was full of ducks which we had shot in late November and early December. Aunt Doris was a wonderful cook and we all loved roast duck. And so, when we had finished off the ham, bacon and a few lamb shops there was still a good supply of fresh meat. We enjoyed roast duck for just about every noon meal until the county graders were able to plow us out.

As the weather cleared, the ducks continued to fly in and out of Winter Creek. However, there was significant death loss. I don’t know if the birds actually froze to death like the cattle and sheep, or whether they suffocated from the wind-driven snow. A businessman from Scottsbluff named John Cook had built a substantial feedlot at the headwaters of Winter Creek adjoining Uncle Mart’s farm on its northeast corner. The feed lot had no shelter and was enclosed with a four- or five-strand barb wire fence. About one week before Christmas, he brought in fifteen hundred steers from Mexico. They were never “backgrounded” and were not ready for the strong wind and sub-zero temperatures. When the storm subsided there was not a single steer left in the feedlot. They broke out or drifted through the fence and more than seven hundred were never found. However, they all had one thing in common—they were all graveyard dead. Some froze standing up. Others drifted into draws and ditches and piled up like chord wood. It was what one might call “one helluva mess.”

Meanwhile, rescue operations were underway. DC-3 cargo planes with loads of feed, food and fuel would fly over and drop their cargo where needed. If you needed something you would tramp out a letter in the snow. L was for food, F was for fuel, and I think C was for cattle feed. Marty, Johnny and I wanted to spruce up our diet, so we went out and tramped a large L in the snow. Uncle Mart (who could swear with the best of them) had a bad case of glandular infuriation, approaching apocalyptic status. We rubbed out the L before it was spotted by the rescue planes—so we continued to eat the roast duck and potatoes.

While we had overdosed on mallard ducks, they sure tasted good, and the wild mallard is still my favorite meat. It is even better than steak, boiled okra, or even raw oysters. I hope that Mother Nature and sound conservation efforts by Game and Parks, Ducks Unlimited and Delta Waterfowl will continue to preserve a strong and renewable population of this magnificent bird.

A handwritten note on the back of this photo explains the scene: “150 beef cattle caught in natural death trap, none survived. Driven before the wind, the cattle wandered out on the glassy surface of the lake near Ashby. One by one they fell and were unable to rise. Jan. 2-5, 1949.” The photo was taken February 3 by Frank L. Spencer. History Nebraska RG3139-0-117

While the blizzard killed several hundred thousand head of cattle on the central and northern plains, decimated upland game populations, and caused great misery for everyone, three cousins had a great time of it.

There were some other negative and positive aspects of the great blizzard. The cousins each missed two weeks of school-but we didn’t mind at this stage of adolescence. I learned at least seventy-five different poker games—enough to last me through six years of college and two years of active duty in the Navy. This, in turn, helped me “learn when to hold ’em and learn when to fold ’em.” My share of the profits from trapping muskrats ran to about $40.00.

(01/04/2021)

Read more about the winter of 1948-1949 in this special issue of Nebraska History Magazine (PDF).