This article appears in the Winter 2023 issue of Nebraska History Magazine, a quarterly publication of History Nebraska. Family-plus members receive four issues per year. The print layout (PDF) of this article, with additional photos, is posted here.

By Leo Adam Biga

Theaters across the nation claim alums who have gone on to Broadway and Hollywood careers. The Pasadena Playhouse, Steppenwolf, Goodman, Alliance, and Guthrie theaters come to mind. Few if any American theaters, though, own the lineage the Omaha Community Playhouse (OCP) has enjoyed with a single thespian family, the Fondas.

They are not only the Playhouse’s First Family of Stage but one of America’s preeminent acting families. The dramatic arts line of Henry Fonda, Jane Fonda, and Peter Fonda extended to three generations with Peter’s daughter, Bridget Fonda, a one-time fellow A-lister now retired from the industry, and Jane’s son Troy Garrity, a veteran film-television actor still active on screen.

The last Fonda to perform at the Playhouse was distant cousin Matt Fonda, who appeared in a 1977 production of Cabaret. Even though a Fonda hasn’t acted there since then, Fondas have returned for nostalgia-fueled visits, tributes, and fundraisers.

This year, OCP’s 100th anniversary season kicks off in September, and special events commemorating its centennial are planned throughout the 2024-2025 season.

The Fonda legacy is bound up in the story of the Playhouse, which Henry often referred to as “the little theatre,” not in a condescending but affectionate way that encapsulated his relationship with the place. The phrase also reflects that the Playhouse was formed in the wake of the national Little Theatre movement that saw towns, large and small, across America launch nonprofit community theaters dedicated to artistic experimentation and liberation from commercial theater concerns. From the start OCP was more commercial-minded than many of its peer little theaters and has remained so to this day, though it also owns a long history of staging avant garde or experimental works in its more intimate studio space, which has been home, appropriately, to the Fonda-McGuire Series.

Henry (1905-1982) was the patriarch of both a powerhouse acting family and, in a real sense, of that beloved “little theatre” where the magic first happened for him. The Playhouse not only represented the origin story of his lifelong vocation, but it also embodied for him what pure theater is all about. As a purist himself he believed in staging stories for the sheer love of it ahead of any monetary considerations.

A robust membership base has supported the nonprofit since its 1924 founding. In classic community theater fashion, it operated as an “amateur” house for decades, with only the director paid. Volunteers filled the gap. Over time it outgrew that model and began employing a full professional staff on both the artistic and business side of things. Where before only select actors and crew members were paid, all are now compensated.

Henry Fonda being interviewed by KOIL radio report Bob Cunningham at the Omaha Municipal Airport circa 1938. When Cunningham asked what the Omaha Community Playhouse had done for him, Fonda joked about his early years as a struggling artist, saying, “They made a bum out of me.” RG4006-4-6

Building Blocks

Henry got his start there during the height of the Jazz Age in 1925. His first performance came at the Mary Cooper Dance Studio near 40th and Farnam, one of a series of temporary performance spaces the Playhouse occupied in its earliest years. It was 1928 when the Playhouse opened its first permanent home, built on Sarah Joslyn’s cow pasture at 40th and Davenport.

Henry was encouraged to get involved by his mother Herberta, a volunteer, and by the mother of another native Nebraska acting legend, Marlon Brando. The year the Playhouse formed, Marlon was born to Dorothy “Dodie” Brando, a founding member. Dodie starred in OCP’s first play, The Enchanted Cottage, in 1925. Henry’s sister Jayne co-starred in the show. The Brandos and Fondas knew each other socially and as the theater’s inaugural 1925-26 season neared, Dodie, along with Henry’s sisters and aunts, cajoled the strikingly handsome but shy Henry to try his hand at stagecraft.

“I was too shy to say don’t do this to me,” he told the BBC’s Michael Parkinson in a 1975 interview. “I didn’t think about doing it, somebody else thought about it, and I got pushed. It never occurred to me to be an actor. I did not grow up going to movies thinking I wanted to be a movie actor. I was out of college. I studied journalism … I thought I was going to be a writer. My grandfather sort of encouraged that.”

Henry, an Omaha Central High School graduate who never participated in any school dramatic productions, left the University of Minnesota journalism program long before finishing his degree. The twenty-year-old was back living at home, stuck for what to do with his life, when fate intervened in the form of a play in urgent need of a young man.

Greg Foley was set to direct the Philip Berry play You and I, and when Foley struggled finding someone to play the juvenile lead, Dodie Brando volunteered to recruit the young Fonda.

“It wasn’t that she thought I had talent, I was just the right age. That’s how it happened,” Fonda told Parkinson. “I don’t remember the experience of playing that part. What I remember are physical things like being on stage before the curtain goes up and hearing the buzz of the audience behind the curtain. And then when the stage manager gives the cue for the house lights to go down, that buzz starts to get quiet. For the rest of the year I didn’t act.”

He painted scenery, built sets, rigged lights, and ushered. To his surprise, he’d found a home in this milieu of make-believe, drawn to the teamwork and camaraderie of making words and ideas live on stage. The bug bit him hard. Not that he wanted to be an actor, necessarily, but being part of a collective effort that held an audience spellbound enthralled him. “I practically lived at the Playhouse. I had so much fun.”

When offered the lead in the next season’s opening production, Merton of the Movies, Fonda accepted it against the wishes of his taciturn, no-nonsense father, W. Brace Fonda, who owned a downtown printing press. His father thought his son was jeopardizing his day job as a file clerk by rehearsing for the play at night. The two argued and then didn’t speak to each other despite living under the same roof.

In one of the great art-imitating-life interludes on record, Fonda fell in love with acting during rehearsals of this comedy playing a store clerk who fantasizes about being a movie actor. On opening night his family came but by pre-design didn’t congratulate him backstage after the show but instead went home to await his return. Henry arrived home to find his stone-silent father ensconced in his favorite chair, reading a newspaper, with no greeting or mention of the play.

Describing the scene to Parkinson, Fonda said, “He doesn’t speak to me so I pass him and I join my sisters and mother, and they just went on with extravagant praise for like 10 minutes. And then my sister started to say something that sounded like it was going to be less than, ‘At one point, I thought if only …’ and she only got about that far and Dad said, ‘Oh, shut up, he was perfect.’”

Though the practical father seemingly frowned on the son pursuing something as frivolous as acting, his unexpected and unsolicited praise for his son’s stage debut still made Henry tear up when recalling the memory on the Dick Cavett Show fifty years later.

The Playhouse became very much a Fonda family enterprise. Henry’s sisters Harriet and Jayne appeared in early productions. Jayne’s stage debut had come in the Playhouse’s inaugural show, The Enchanted Cottage. Harriet won praise as a princess in The Romantic Age in early 1926. All three Fonda siblings were in He Who Gets Slapped in OCP’s second full season. A cousin, Douw Fonda, appeared in Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle in 1928, shortly before Henry left his post as Playhouse assistant director for a professional acting career.

Even Henry’s remote father got into the act by appearing in the play Seventeen. More in character for the business-minded senior Fonda, he served as secretary of the Playhouse Building Association, which raised funds for the first Playhouse, and as a trustee during the Depression years.

Considering where Henry Fonda grew up and the family he came from, it’s safe to say he would likely have never even tried acting if not for his mother’s and sisters’ involvement at the Playhouse and the Brando association. It is worth noting, too, that Henry’s stage start came only six years after witnessing the 1919 Red Summer mob lynching of Will Brown outside a besieged Omaha courthouse. The event left a deep imprint on him and figured into some of the work he did. He was fourteen when he and his father watched the horror unfold from the second story window of his father’s print shop. In the 1975 interview with Michael Parkinson he emotionally recounted the profound impact that event had on him.

“My father never talked about it. He never preached about it. We both just were observers … It was the most horrendous sight I’d ever seen … My hands were wet and there were tears in my eyes. All I could think of was that young Black man dangling at the end of a rope.”

Not by coincidence Fonda went on to star in the classic social justice movies The Grapes of Wrath, The Ox-Bow Incident, and Twelve Angry Men. He capped his stage career with a tour de force one-man show as progressive attorney and civil rights champion Clarence Darrow.

It was also crucial that Fonda got started between two world wars and at the height of silent movies. By the time he fell in love with theater, his sights were set on the legitimate stage. Broadway commanded prestige compared to vaudeville and burlesque, which is important to note because actors and other show business people were widely disdained by “good society.” On the other hand, the immense popularity of vaudeville, Broadway, radio, and film gave performers a new degree of respect. Though Henry initially focused on theater rather than film, his experience on stage prepared him for the sound era of cinema that matured just as he went West to pursue a Hollywood career. A child of both the talkies and the footlights, he brought a realism to his dialogue and behavior that came across as genuine, never phony.

In a 1981 Tonight Show appearance Fonda shared with host and fellow Nebraska WASP Johnny Carson the spell acting cast on him.

“I get a real joy out of acting, mostly in the theater. I love to act, just because I’m somebody else. It’s pretending you’re somebody else and I found 55 years ago you could get paid for pretending you’re somebody else.”

On stage, wrapped up in a role and scene, he said, he forgot his natural reserve and self-consciousness.

“I’ve got a mask on and I can get out there and be the guy that the playwright conceived to be – funny or smart, all the things I’m not. It’s therapy.”

As a young man learning the ins and outs of theater, he said, he realized a satisfactory experience on stage was not complete if even for a second he was conscious the players were acting.

“I kept thinking if you can make the audience forget they’re watching a performance …”

Indeed, Fonda was from the same school of acting as contemporaries James Cagney and Spencer Tracey, who famously said acting came down to learning your lines, listening, and telling the truth. In other words, never let them catch you acting.

The unaffected style of acting he perfected became his trademark and the envy of both his contemporaries and of Method Acting adherents. Not one to self-examine how he arrived at his naturalism, he preferred to let it remain a mystery or gift lest he become overly conscious of it and somehow lose it.

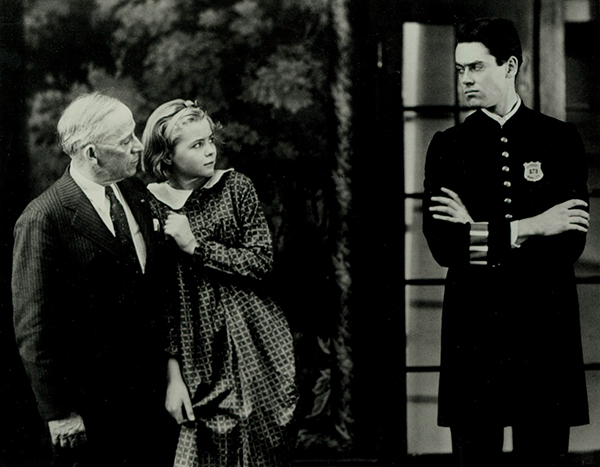

The young Fonda found success in New England with the University Players and fellow stars-to-be James Stewart, Margaret Sullavan, Kent Smith, and Joshua Logan. In 1930, still a few years away from making it to Broadway and Hollywood, a matured Fonda returned to Omaha to appear with the Playhouse’s newest prodigy, thirteen-year-old Dorothy McGuire, in A Kiss for Cinderella, at the behest of Playhouse director Bernie Szold. It was the first and last time Fonda performed on the Davenport Street theater stage.

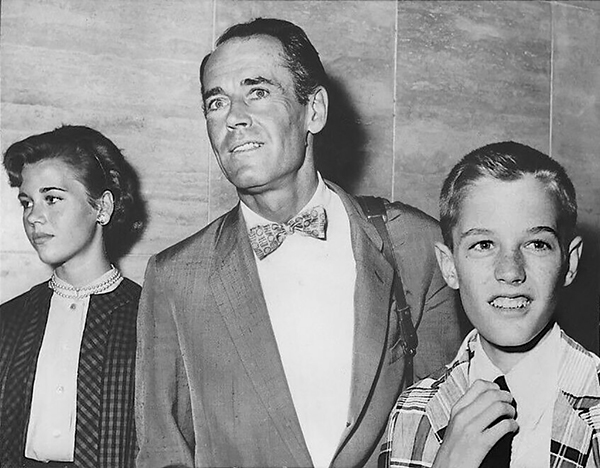

Henry Fonda and Dorothy McGuire in A Kiss for Cinderella (1930). Both went on to become major stars of stage and screen. Courtesy Omaha Community Playhouse

In the mid- to late-1930s, the Playhouse hit its stride under a succession of directors, and Fonda, by then a film star, bought new seats for the theater. He became a star on Broadway in The Farmer Takes a Wife (1934) and instantly became a Hollywood star when he reprised the role in the 1935 film adaptation directed by Victor Fleming. It marked his movie debut.

Loyal to His Roots

One of the things that distinguished Fonda from all but a handful of fellow Nebraskans to find success in Hollywood was the close relationship he maintained with the state, principally through the Playhouse, but also with the town of his birth, Grand Island (the Fondas moved to Omaha when he was a year old) and its Stuhr Museum of the Prairie Pioneer.

As the old saying goes, he never forgot where he came from. He often came back to his hometown and theatrical home. On three of those occasions he appeared with fellow screen-stage acting legend Dorothy McGuire, who made her debut there less than a decade after he emerged at the Playhouse. In recognition of the actors’ contributions to Playhouse lore, various programs and honors bear their names, including the prestigious Fonda/McGuire Award given to an actor and actress for outstanding performance.

McGuire, born in Omaha in 1916, may be unfamiliar to all but a few stage-cinema buffs today, but she conquered Golden Age Broadway, film, and television. In New York she took over from Martha Scott as Emily Webb in the original production of the Thornton Wilder classic, Our Town, directed by the legendary Jed Harris. Times critic Brooks Atkinson praised her lead performance in the 1941 Broadway play Claudia, which led to her reprising the titular role in the 1943 film adaptation co-starring Robert Young. Early in her film career McGuire worked with Golden Era heavyweight directors such as Edmund Goulding (Claudia), Elia Kazan (A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Gentleman’s Agreement), and Robert Siodmak (The Spiral Staircase), and later went on to work with Mark Robson, Edward Dmytryk, William Wyler, Henry King, Delmer Daves, Delbert Mann, and George Stevens.

Henry and Dorothy never shared the screen together, but in 1955 they teamed for an Omaha Community Playhouse benefit production of The Country Girl. It was the hottest ticket in town. Only that bow didn’t happen at the Playhouse itself, which was too small to accommodate the anticipated crowds. Instead, the show went up at the new Omaha Civic Auditorium Music Hall. The benefit performances raised money for construction of the new Playhouse at 69th and Cass. Built in 1959, the new, larger facility stood near three of Omaha’s most iconic neighborhoods – Dundee, Fairacres, and Aksarben – and was easily accessible to emerging suburbs on the city’s expanding western borders.

Other stars have returned to hometown theaters, but one would be hard-pressed to find another theater so far removed geographically from Broadway and Hollywood that managed to get not one, but two name-above-the-title alums to return for the same show during the height of their careers. The production also co-starred another Omaha actor who went on to a long stage-screen career, James Milhollin, best remembered for playing frazzled authority figures. But what put this teaming over the top was the presence of Jane Fonda, soon to be a star in her own right, joining these veteran performers on stage.

Henry Fonda signs his Ak-Sar-Ben membership papers, 1941. RG3882-2-736

Jane’s Coming Out Party

Jane’s stage debut came in the middle of the Cold War and Beat Generation, when with trepidation she appeared opposite her famous father as a seventeen-year-old ingénue. She was a raw beginner in Country Girl, exposing herself not only to the scrutiny of a hometown audience, but also to that of her father. Added to this pressure was the knowledge that the future of the Playhouse was riding on the production’s success.

A recent graduate of the Emma Willard Academy and a soon-to-be enrollee at Vassar College, Jane wasn’t sure she even wanted to be an actress. She was trying out her acting chops alongside two long established stage and screen stars – one of them her father – whom she idolized but whose emotional guard she could not penetrate. Adding to the potent off-stage dynamics, the play’s plot was set amidst a theater milieu and an emotionally absent actor.

Jane agreed to do the play at the urging of her Aunt Harriet, one of those who prodded Henry to try acting in the first place, and of family friend Joshua Logan, the director who helmed her father’s greatest stage success, Mister Roberts. Logan went on to direct Jane in her Broadway and film debuts, There Was a Little Girl and The Tall Story, respectively.

She won the role in a New York-to-Omaha telephone audition with Playhouse director Kendrick Wilson. She insisted she had no aims to pursue acting as a career. “I have no talent. Besides, directors intimidate me.” In a 1955 San Bernardino Sun article whose reporter caught up with Jane during Country Girl rehearsals, the actress said she sought the role solely for the chance to be on stage with her father. “I always wanted to work with Father.”

Henry was asked how he would feel about his daughter carrying on the family trade. “It wouldn’t bother me. I have never told her this, but the most important thing is to have talent.” Asked if he thought she did, he demurred by saying, “no comment.”

Jane, meanwhile, learned a new appreciation for her father’s craft and method. “I never knew that when you acted you felt the part as he apparently does. When he works, he doesn’t think of anything else. I wish I had that much perseverance.”

Not surprisingly, the star pedigree and hometown buzz sold out all three performances of The Country Girl weeks in advance. Stars of Fonda’s and McGuire’s magnitude rarely came to Omaha, and the public craved seeing three of their own live on stage. And though Jane’s part was small, crowds were naturally eager to see whether the beautiful-but-untested daughter of their favorite leading man would follow in her father’s footsteps or fall flat on her face.

Jane told a writer she resorted to having a crew member slap her backstage to evoke the tears a scene demanded, thus displaying an early instinct for doing whatever it took to make it real.

No film footage of Jane and Henry in Country Girl is known to exist. Even if it did, it’s unlikely it would reveal the real-life tensions between them, even though they were perhaps more potent than the play’s plot line of a strong woman supporting a weak man.

No one could have imagined that the daughter’s career would eventually eclipse the father’s, much less that she would go from modeling to playing debutantes to pop culture sex heroines and prostitutes to fledgling feminists/activists, or that she would elicit the hatred of many Americans for her brazen, naive photo-ops with members of a Vietcong anti-aircraft battery.

Joining the “family business,” Jane and her brother Peter (1940-2019) may have felt obligated to prove their mettle in the city where Henry came of age. Peter made his debut in Omaha in a 1961 production of The Golden Fleecing. His father and sister came to see him in it. Peter appeared in a second Playhouse production that same year, The Pleasure of His Company. He eventually attended the then-University of Omaha (now the University of Nebraska at Omaha).

Peter came to symbolize youthful rebellion through the biker films he made in the ’60s, capped by the wild success of Easy Rider, a film he wrote, produced, and co-starred in. The film’s success gave him the means to make his own indie projects, such as The Hired Hand (1971). One of his final directorial efforts, Wanda Nevada (1979), marked the only time father and son appeared together in a film.

For both siblings, the Playhouse became more than their father’s legacy. Even years after they appeared on its stage, each returned to visit the theater. Peter accepted a lifetime achievement award from the then-Sheldon Film Theatre (now Mary Riepma Ross Media Arts Center) in Lincoln, Nebraska, and was known to show up unannounced at the Playhouse to get his nostalgia fix. Jane spoke about her life and career with filmmaker Alexander Payne before a live audience for a 2012 Film Streams fundraiser at the Holland Performing Arts Center in Omaha, where she made time to tour the Playhouse. In the lobby outside the Hawks MainStage she could not miss the mosaic of photographs featuring Playhouse notables of past and present, her father among them.

Jane has told interviewers that she initially treated acting as “a romp” or passing fancy, but she saw things differently when her family got close to the Strasbergs and she fell under the influence of the Svengali-like Lee Strasberg of Actors Studio fame. Jane Fonda biographer Devin McKinney wrote that conversations and studies with Strasberg gave her “permission to take the romp seriously and a vocabulary to define what her father” refused even to discuss.

Only five years after Country Girl and less than two years after becoming a disciple of The Method, she was on Broadway in There Was a Little Girl. Despite the fact the play was panned and closed after only sixteen performances, she was praised, even earning a Tony nomination as Best Featured Actress. Her second Broadway foray, Invitation to a Match under the direction of Jose Quintero, ran three months and helped establish her as a bonafide stage presence.

Her next Broadway appearance came in 1963’s production of Eugene O’Neill’s Strange Interlude, again under the direction of Quintero, and playing in a talent-rich cast that featured Betty Field, Geraldine Page, Ben Gazzara, Pat Hingle, Geoffrey Horne, Willam Prince, Franchot Tone, and then-child actor Richard Thomas.

Given the auspicious start of her stage career, no one could have predicted that Strange Interlude would mark Fonda’s last Broadway stage role until her much anticipated and critically lauded comeback in 2009’s 33 Variations. But when offers from Hollywood began flooding in following high profile model and stage work, she abandoned Broadway for a series of films that, though forgettable, established her as a plucky, gorgeous ingénue with box office appeal, topped by the hits Cat Ballou and Barefoot in the Park. This coincided with a European period that saw her work with then-filmmaker husband Roger Vadim and other French directors who pushed her new sex kitten image to new lengths in La Ronde, The Game is Over, Barbarella, and Spirits of the Dead. She returned to the States to remake her image as a serious actress, which she accomplished with They Shoot Horses Don’t They?, Klute, A Doll House, Coming Home, Julia, and The China Syndrome, becoming in the process one of New Hollywood’s major dramatic stars.

Stoic Everyman

Given how much Jane sought approval from her father, playing opposite him in 1955 was nerve-wracking. Though off-screen Henry Fonda was Dad, an impressionable Jane felt the weight of him as the iconic interpreter of Abraham Lincoln (Young Mr. Lincoln), Tom Joad (The Grapes of Wrath), Wyatt Earp (My Darling Clementine) and Gil Carter (The Ox-Bow Incident).

Like many of the characters he portrayed on screen, Henry projected terse stoicism in real life. During those relatively rare times he was at home with his children, he was emotionally distant. Open displays of feelings did not suit him. He didn’t say much and what he did often seemed critical. He famously avoided talking about his craft with his children even after they expressed interest in it and pursued it professionally. Like his sister Jane, Peter publicly shared his own difficulties breaking through his father’s icy reserve to get anything that felt like affection and validation. Fifteen years after his father’s death, Peter seemingly channeled the old man’s persona in Ulee’s Gold, a 1997 film that earned Peter his only Best Actor Oscar nomination. It was a film and performance Henry would have approved.

This reserved, mercurial quality of Henry’s, combined with his piercing eyes, sense of decency, and native intelligence seduced audiences into believing him as everything from cowboys to presidents. As much as he owned the screen, his commanding presence on stage was legendary for the sheer charisma and control he brought to roles.

From 1948 until 1951, he played the Everyman title character Doug Roberts in Mister Roberts, among the most popular plays in Broadway history up to that point. Recently discharged from the U.S. Navy, Henry wore his own uniform in the play. He went on for more than 1,100 performances, never missing a single show. He toured with the production for nearly another full year, bringing his greatest triumph back to where his life on stage began, Omaha, for four performances at the long-since-razed Omaha Theatre.

A true theater aficionado, Fonda enjoyed intersecting with one of America’s oldest stage houses – The Walnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia, where Mister Roberts opened its Broadway tryout. In the late 1960s, Fonda, along with fellow thespians Robert Ryan, Mildred Dunnock, Estelle Parsons and Martha Scott, began a theater company that took its name, Plumstead, from the historic Plumstead Playhouse in Philadelphia. The new Plumstead operated in Long Island before moving to Pasadena.

Following his nostalgic Omaha turn in Country Girl, Henry added to his portrayals of social justice bastions with his screen appearances as Juror #8 in 12 Angry Men, as Robert Leffingwell in Advise and Consent, as the President of the United States in Fail-Safe, and as William Russell, a character patterned after Adlai Stevenson, in The Best Man.

His ability to be bigger than life and yet disappear within his characters is why top directors as diverse as Henry Hathaway, John Ford, Fritz Lang, William Wyler, Henry King, William Wellman, Preston Sturges, Otto Preminger, Sidney Lumet, Alfred Hitchcock, Anthony Mann, Delmer Daves, Don Siegel, and Sergio Leone worked successfully with him. In all the storylines, locations, and soundstages of his Hollywood career, Fonda almost never ventured from the basic decency he first displayed at the Playhouse. The one notable time he went against type, in Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), he created a chilling villain in Frank. As jarring as that performance was, it still came down to Fonda playing make-believe the way he had all those years before In Omaha. Only the medium, the craftsmanship, and stakes had changed.

His later stage triumph as Clarence Darrow served as the capstone for his stage career. He played the role on Broadway and then toured with the show for two years. He turned seventy during its run. Fonda told Michael Parkinson, “I feel lucky at this age. You do start to slow down. Whether you retire or not, there are fewer parts for 70-year-olds. But when a play like Clarence Darrow [1974] is sent to you and it’s exciting as a play and as a man – I fell in love with this man when I read it – you just don’t not do it.”

In answer to Parkinson asking if he contemplated retiring from the stage, given his recently implanted pacemaker, and why he kept coming back for more, Fonda said, “It’s a joy. As long as it remains a joy, why not? I wouldn’t think of not doing it.”

Just as Darrow was the pinnacle of his late Broadway and touring experiences, On Golden Pond provided the Best Actor Oscar he had never won from his Hollywood peers. That project afforded Jane a final opportunity to connect with him both personally and professionally.

Henry Fonda and Dorothy McGuire shared the Omaha Community Playhouse stage for a 1981 tribute program, An Evening with Mr. Fonda, that served as a valedictory for his career. The event was organized by Fonda’s longtime publicist and friend, John Springer. Son Peter and grandson Justin came to honor their father, and Jane paid tribute via film clips.

Henry died the following year, shortly after Jane accepted his only Best Actor Academy Award for On Golden Pond. Jane had optioned the Ernest Thompson play of the same name as a vehicle for herself and her father. To star opposite him she recruited a contemporary of her father’s, the great Katharine Hepburn. The two old stars had never worked together. Jane produced and for the second time ever – and the first and last time on screen – she co-starred opposite her father. In a grace note and nod to her father’s affection for Nebraska, she headlined a premiere of the film at Omaha’s grand Orpheum Theater that raised funds for the family’s favorite cause, the Playhouse.

“There are no words to describe my emotions. To have the premiere of the movie here, for this cause … it’s so right,” she told the Omaha World-Herald.

Henry Fonda’s high points with the Playhouse came at four distinct phases of his life and career. The green-but-game Fonda showed promise in the 1920s, but no one would have predicted what came after – least of all himself. When he returned in ’31 he was a seasoned young pro, secure in his talent and technique and still hungry for more. He was a star in the making, though no one yet knew just how far his skill, ambition, and looks would take him. By the time he returned in ’55 he owned the recognizable name, face, and voice of an iconic leading man on stage and screen. He carried with him, too, the imprint and identity of the iconic characters he played – Abe Lincoln, Frank James, Tom Joad, Wyatt Earp – lending him a certain weight and persona and mythology.

For his final Playhouse appearance in 1982, Fonda was old and frail and yet still projected the nobility and dignity of progressive figures he played, such as Juror 8 in 12 Angry Men, Robert Leffingwell in Advise and Consent, William Russell in The Best Man, and the American President in Fail-Safe. But he also never lost the charms of the earnest romantic interest (Jezebel), hapless socialite (The Lady Eve), stern gunsel (The Tin Star, Warlock), and laconic, unpretentious, down-to-earth regular Joes (The Wrong Man, Spencer’s Mountain, The Cheyenne Social Club) that he also played. In other words, he represented many different facets and faces depending on the roles he undertook, and he acted them so convincingly that audiences couldn’t shake loose of them when they saw him.

Keeping the Legacy Intact

By the time young Henry left Omaha to pursue an acting career back East, the Brandos had left Omaha, and thus Dodie never got the chance to push Marlon and his sister Jocelyn on stage there. It’s possible that Omaha natives Fred and Adele Astaire, Montgomery Clift, and other future legends might have performed there, too, had their families not moved before the Playhouse entered its formative years. Even during its reign as Nebraska’s preeminent theater, many other Nebraska natives who went on to stage stardom, such as Stephanie Kurtzuba and Andrew Rannells, never performed there for one reason or another. In the case of Q. Smith, her performing came at other Omaha theaters before making her way to New York and Broadway. While growing up in Omaha, Kevyn Morrow never performed on the OCP MainStage but the Broadway veteran came back by special arrangement to headline a production of Ragtime.

Omaha native Julie Wilson, the late stage-screen actress turned New York City cabaret legend, did make her acting debut there. So did another Omaha native, Lenka Peterson, a veteran of stage and screen. She won the Fonda/McGuire Award. She went on to be one of the first members of the Actors Studio and was Tony-nominated for Best Featured Actress in a Musical for Quilters. Screen actor Terry Kiser got his start there in the early ’60s alongside Peter Fonda. Noted stage-screen actor Norbert Leo Butz performed with the OCPs touring arm the Nebraska Theatre Caravan.

Nebraska may seem an unlikely birthplace for stage-screen stars, but it’s produced more than its share considering its small population. See a select roster of Nebraska stage-screen legends at the bottom of the story.

Since Henry Fonda’s death in 1982, his wife Shirlee, who accompanied him to Nebraska on several visits, has remained connected to the Playhouse, providing financial support for its youth programs. The Shirlee & Henry Fonda Theatre Academy offers classes and camps devoted to the theater arts. No such formal theater training existed at the Playhouse when Hank, as friends called Henry, learned the ropes as a young man. OCP’s focus on youth has been a key feature of its education programming for decades. While most students do not end up making a career in theater, film or television, some do; therefore, it’s always tempting to wonder who might be the next Henry Fonda or Dorothy McGuire to graduate from the Playhouse onto bigger stages.

Perhaps the best way to measure what Hank meant to the Playhouse is the building it occupies today, the construction of which was made possible in part by the proceeds from The Country Girl performances. He also lent his name and voice to its fundraising campaign, something he did for other Playhouse drives. The humble Fonda resisted efforts to rename the Playhouse after him, believing it would detract from the “let’s-put-on-a-show” community aspect that made it Omaha’s and Nebraska’s theater.

The building has seen renovations and additions in recent decades but some of the guts are original to the structure’s 1959 build.

Despite his and perhaps his widow’s reservations about his name and likeness being given top billing lest they overshadow the Playhouse, it would seem fitting that the theater hold an annual Henry Fonda or Fonda Family Film Festival. After all, new generations of theater creatives and patrons may not know his or Jane’s or Peter’s work. What better time than the Playhouse’s 100th anniversary to inaugurate a celebration of this family’s acting heritage. Truly, the history of that theater is inextricably tied to that family. If Henry were alive today he would undoubtedly say he got the better end of the deal in that pairing. But the Playhouse is certainly fortunate to have its legacy tied with his, Jane’s, and Peter’s. They are an integral part of the story of how this little-theater-that-could has become an institution now a century strong and counting.

<sidebar>

Nebraskans On Stage and Screen

Nebraska’s on-stage and on-screen talents through the years include: Harold Lloyd; Fred and Adele Astaire; Robert Taylor; Ward Bond; Henry Fonda; Dorothy McGuire; Julie Wilson; Colleen Grey; Montgomery Clift; Marlon Brando; Lenka Peterson; Johnny Carson; David Janssen; Philip Abbott; James Coburn; Inga Swenson; Dick Cavett; Sandy Dennis; Terry Kiser; Paul Williams; Swoosie Kurtz; Jo Ann Schmidman; Nick Nolte; Marg Helgenberger; Anne Ramsey; Kevyn Morrow; Lori Petty; Jaimie King; John Beasley; Gabrielle Union; Yolonda Ross; Bryan Goldberg; Merle Dandridge; Stephanie Kurtzuba; John Lloyd Young; Andrew Rannells; Q. Smith; Michael Beasley; Amber Ruffin; Chris Klein; Nicholas D’Agosto; Adam Devine; Nadia Rashawn.

Behind-the-screen, off-stage talents from Nebraska form an equally impressive legacy: Fred Niblo; Ann Ronell; Darryl Zanuck; William Dozier; Lew Hunter; Donald E. Thorin; Joan Micklin Silver; Gail Levin; Mike Hill; Sam Johnson; Alexander Payne; Jon Bokenkamp; Kevin Kennedy; Patrick Coyle; Dan Mirvish; Rachel Shukert; Erich Hover; Charles Hood; Chanelle Elaine; Ray Mercer; Beaufield Berry