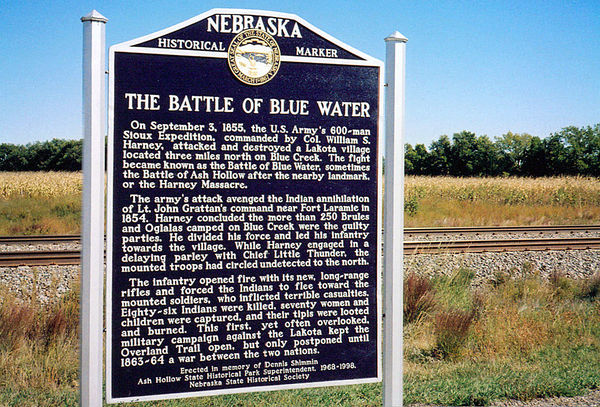

Marker Text

On September 3, 1855, the U.S. Army’s 600-man Sioux Expedition, commanded by Col. William S. Harney, attacked and destroyed a Lakota village located three miles north on Blue Creek. The fight became known as the Battle of Blue Water, sometimes the Battle of Ash Hollow after the nearby landmark, or the Harney Massacre. The army’s attack avenged the Indian annihilation of Lt. John Grattan’s command near Fort Laramie in 1854. Harney concluded the more than 250 Brules and Oglalas camped on Blue Creek were the guilty parties. He divided his force and led his infantry towards the village. While Harney engaged in a delaying parley with Chief Little Thunder, the mounted troops had circled undetected to the north. The infantry opened fire with its new, long-range rifles and forced the Indians to flee toward the mounted soldiers, who inflicted terrible casualties. Eighty-six Indians were killed, seventy women and children were captured, and their tipis were looted and burned. This first, yet often overlooked, military campaign against the Lakota kept the Overland Trail open, but only postponed until 1863-64 a war between the two nations.

Location

19568-19570 Nebraska 92 Scenic, Lewellen, Garden County, Nebraska

Further Information

The Battle of Blue Water, also called the Harney Massacre and sometimes erroneously referred to as the Battle of Ash Hollow, was an engagement in the First Sioux War. The conflict, which occurred on September 3, 1855, resulted in the deaths of 86 Sioux and 12 US soldiers. The raid was a retaliatory strike after the so-called Grattan Massacre near Fort Laramie the year before.

Background The Platte River Road passed through the domains of several Indian tribes. The largest of these was the Great Sioux Nation. During the first stage of westward migration in the 1840s, the Indians acted peacefully towards the white migrants. In the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, the government agreed to recognize tribal authority and give aid to the Indians in return for the guaranteed safe passage of migrants. The peace between the whites and the Indians didn’t last long. Pioneers liked to hunt buffalo but, unlike their Native counterparts, tended to overhunt the animals. As buffalo herds decreased, tensions between whites and Indians increased.

The Grattan Massacre The first major engagement between the Sioux and the Army was the result of a missing cow. When a Mormon migrant’s cow wandered into Sioux territory, some young Sioux killed and ate it. The migrant reported it as a theft. Lieutenant John Grattan led 29 men into Sioux territory on August 19, 1854, to arrest the culprit. An argument ensued, which led to the death of Chief Conquering Bear. In response, the Indians killed Grattan and his 29 men. Military men and others urged retaliation. Congress appropriated funds for a military expedition against the Sioux, which was to be led by General William S. Harney. For the next year, however, the Sioux were peaceful with the exception of a few isolated incidents played up by the military and the press. A. Cumming, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, urged the government to punish only those who were responsible for the Grattan affair; however, the military was set on attacking the Sioux at large. Superintendent Thomas Twiss of the Upper Platte Agency announced that all friendly Indians in the area should come to Fort Laramie to avoid battle.

The Battle The band responsible for the battle with Grattan arrived at Blue Water in August of 1855. Now led by Chief Little Thunder, these Indians were not expecting war with the whites and did not set up a defensive camp. Some other Sioux and Cheyenne were also with them. About 250 men, women and children total were in the village.

General Harney, stationed at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas, originally wanted 1200 men for his campaign, but eventually settled with 600. He planned to go all the way to the Black Hills and fight the Indians wherever they were. On September 2, Harney and his men crossed the South Platte and entered Ash Hollow. From there they could see the Sioux village at Blue Water. Early the next morning, Harney and about 500 of his 600 men advanced against the Sioux. A detachment of cavalry went to the rear of the village to stage an ambush. Some Indians carrying a white flag came out of the village seeking peace, but the army advanced. The village began to retreat, so Harney called Little Thunder and told him that his band had to pay for the death of Grattan. Little Thunder responded that he could not control the actions of the young people in his tribe, but they wanted peace. Harney insisted on a fight and let Little Thunder go. After the discussions, the army opened fire and chased the villagers into the cavalry waiting at the other end of the village. About 86 Indians, including women and children, were killed and another 70 were captured. The village itself was destroyed. Only 12 soldiers were killed.

Lieutenant G.K. Warren kept a journal of the battle. After the fighting was over, he was sent to recover injured Indians. He described the scene as such:

The sight on top of the hill was heart-rendering, wounded women and children crying and moaning, horribly mangled by bullets… I found another girl about 12 years old laying with her head down in a ravine, and apparently dead. Observing her breath, I had a man take her in his arms. She was shot through both feet.

Another soldier described “a little child naked, save for a scarf around its waist in which a little puppy was wrapped.”

Aftermath The Grattan Massacre and the Battle of Ash Hollow are collectively called the First Sioux War. After these two engagements, the Sioux and the Army did not fight again for about 10 years as the Civil War dominated the Army’s attention in the 1860s.