Ten percent of Nebraskans are Latino, part of a statewide community that is more than a century old. At first it was specifically a Mexican and Mexican-American community. The Spring 2019 issue of Nebraska History tells the story of the early decades.

“By 1930, Nebraska’s Mexican population reached 6,321 people out of a total state population of more than 1.25 million people,” writes historian Bryan Winston. “…They faced limited employment protections, segregation, and discrimination. Employers’ desire for cheap, seasonal labor limited Mexican opportunities for social mobility and relegated Mexicans to specific residences. Then, social workers, local government officials, and intellectuals, while advocating for Americanization classes, used rhetoric about cleanliness and crime to denigrate the social capabilities of ethnic Mexicans. The Great Depression exacerbated economic obstacles for the Mexicans of Nebraska, forcing many to return to Mexico, but did not spell the end of the community.”

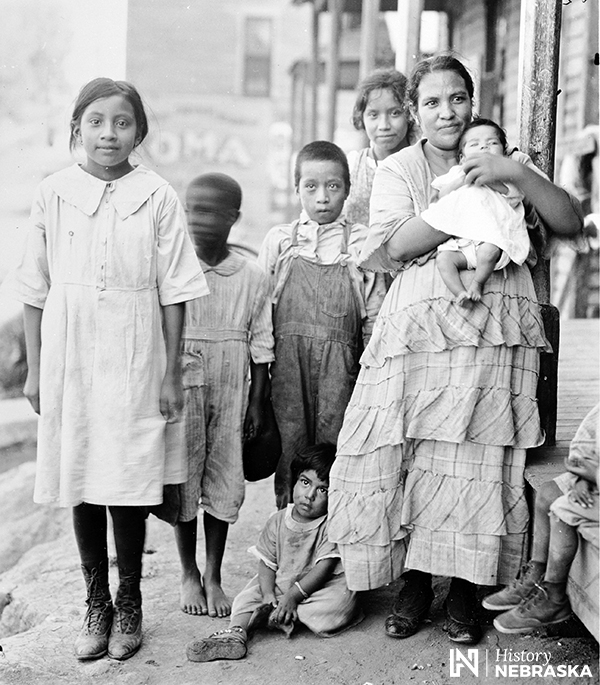

(Above photo: A Mexican woman and her six children, Omaha, August 15, 1922. HN RG3882-PH21-163)

People came seeking work, and like most people they lived near their jobs: the meatpacking district of South Omaha, the neighborhood around the railroad yards of Havelock outside Lincoln, or the farms of Scotts Bluff County.

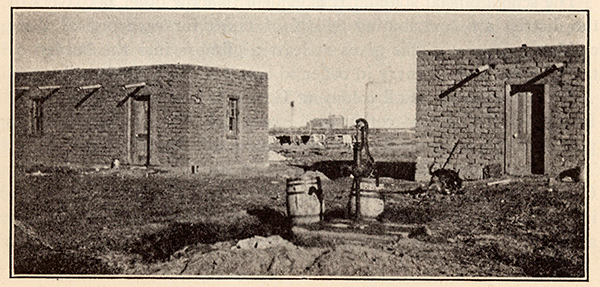

“Railroad workers made boxcars into homes. South Omaha residents often lived as boarders when they “wintered” in the “Magic City” and accepted seasonal employment at the many meatpacking plants. Ethnic Mexicans in Scottsbluff built adobe homes from Nebraskan soil and leftover hay from livestock railroad yards. Bob Huerta recalled how his father, who migrated from Mexico through Texas and Kansas, began building an adobe home in Scottsbluff in 1934. The elder Huerta used soil from his sister-in-law’s yard, straw from railroad livestock reserve cars, and white rock from the nearby sugar factory. He then completed their home, which still stood in 1996, by tearing down the company town shack and repurposing it as a roof for the adobe home.”

Photo: Adobe houses in Scottsbluff, Nebraska. From Sara A. Brown and Robie O. Sargent, Children Working in the Beet Fields of the North Platte Valley of Nebraska (1924).

Under difficult circumstances, how did ethnic Mexicans get by? Winston focuses on community formation, the way individuals and families formed groups and institutions that reached across the state.

“Ethnic Mexicans responded to discrimination and marginalization by creating community organizations and patriotic societies and celebrating their cultural heritage to form social and cultural ties. Ethnic Mexicans promoted cultural bonds through monthly dances, religious practice, and sharing food. At the same time, ethnic Mexicans wrote the Kansas City Mexican consulate to protest wage theft and to seek aid.”

“…By 1919, Mexicans established Omaha branches of Asociación Mexicana Amado Nervo, Comité Patriótico Mexicano, (Mexican cultural and patriotic societies, respectively), and Comité Cátolico Central (a local Catholic organization), as well as Local 602 of the American Federation of Labor.22 This was part of a larger national trend of Mexicans creating organizations that served their communities with cultural celebrations, social services, and workplace protection.”

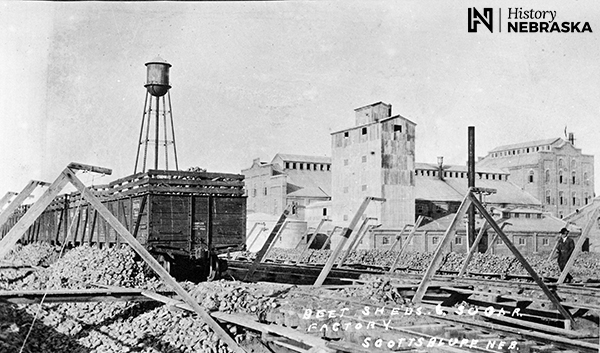

Photo: The Great Western Sugar Company opened a sugar beet refinery Scottsbluff in 1910. The sugar beet industry employed many migrant workers, including Mexicans and Germans from Russia. HN RG2670-PH0-2

This cultural community extended into rural areas.

“Some city-dwelling Mexicans built ties with the agricultural communities that popped up in the spring and summer along railroad tracks and the Platte River, from Grand Island in central Nebraska to Lyman in western Nebraska, practically on the Nebraska-Wyoming border. Some Nebraska Mexican agricultural communities were permanent, with a history as long, if not longer, than that of the Mexican community in Omaha. Ethnic Mexicans settled in the town of Scottsbluff as the thriving sugar beet industry of western Nebraska ensured agricultural employment. Mexican heads of household contracted out acres at a time to work during the harvests. The whole family, even young children, headed into the fields to ensure a productive beet yield for the region’s farm owners.”

Photo: Mexican beet workers visiting the Colorado & Southern and Burlington “Big Beet Special” at Loveland, Colorado, to learn “new methods which would assist in increasing their bonus check,” circa 1926. HN RG1431-2106

In the summer, many families from the Omaha community headed west to work in the sugar beet fields, returning to Omaha in the winter. Pay was low and many families lived in poverty, especially during the Great Depression.

“Lara Campbell, a WPA worker, described ethnic Mexican homes in Scottsbluff as ‘miserable tar-papered shacks, or at best, tiny unplastered wooden buildings—one room divided by a rough partition or a sheet.’ She implored others to ask, ‘would we do better than they under their handicaps and hardships?’” Not all public officials were so understanding. It was common to use the effects of poverty as evidence that Mexicans and other immigrants were unfit for citizenship.

Despite the hardships and prejudice, Winston concludes, “Mexican persistence and creation during the 1920s and 1930s laid the foundation for future generations of ethnic Mexicans and Latinas/os to gain access to economic and political capital in Nebraska.”

Brian Winston is a PhD candidate in US History at Saint Louis University. His article, “Mexican Community Formation in Nebraska: 1910-1950,” appears in the Spring 2019 issue of Nebraska History.

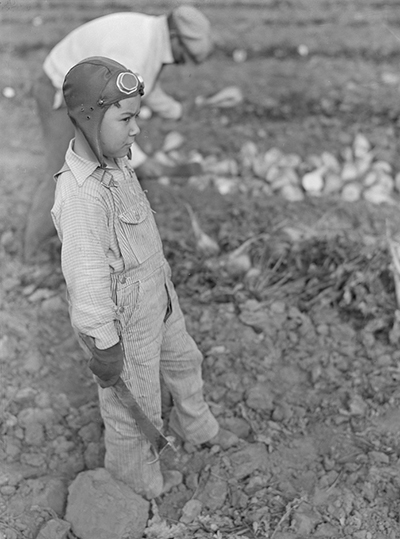

Below: “Mexican boy who works in the sugar beet fields, Lincoln County, Nebraska.” Photo by John Vachon for the US Farm Security Administration, October 1938. Library of Congress