“Uncle Sam is rich enough to give us all a farm.” So proclaimed a popular song from the early 1850s. In that era, good old Uncle Sam undoubtedly had deep enough pockets, enough bread in the cupboard, or, overstated kidding aside, enough real property on the balance sheets to be a national sugar daddy. In fact, the record shows that roughly 270 million acres of the public domain (nearly 422,000 square miles, or about 10 percent of U.S. lands) were eventually given away because of the Homestead Act of 1862. So the real issue for aspiring homesteaders was not so much whether they could get a farm; it was whether they had the gumption and the wherewithal to keep it. Homesteading was an uncertain endeavor. Only about 40 percent of all homesteaders “proved up” on their claims and received a final patent from the federal government. Although the percentage was somewhat higher in Nebraska—a little more than 50 percent between 1863 and 1900—government records nevertheless reflect a cold, hard reality.

“Uncle Sam is rich enough to give us all a farm.” So proclaimed a popular song from the early 1850s. In that era, good old Uncle Sam undoubtedly had deep enough pockets, enough bread in the cupboard, or, overstated kidding aside, enough real property on the balance sheets to be a national sugar daddy. In fact, the record shows that roughly 270 million acres of the public domain (nearly 422,000 square miles, or about 10 percent of U.S. lands) were eventually given away because of the Homestead Act of 1862. So the real issue for aspiring homesteaders was not so much whether they could get a farm; it was whether they had the gumption and the wherewithal to keep it. Homesteading was an uncertain endeavor. Only about 40 percent of all homesteaders “proved up” on their claims and received a final patent from the federal government. Although the percentage was somewhat higher in Nebraska—a little more than 50 percent between 1863 and 1900—government records nevertheless reflect a cold, hard reality.

Records of a different kind, folk songs, show other dimensions of that reality, namely the humanity of the situation. Not surprisingly, many homesteading songs tell of the hardships and deprivations of the homesteading experience. Just as tellingly, though, they illustrate the mindsets of homesteaders in other ways, as their focus and purpose shifted from mostly shared commiseration to determined public action by the latter decades of the 1800s. To put it another way, these songs were at first a salve, then a sword for these struggling but determined pioneers.

In Nebraska at least, the greatest flourish of songs responding to the human consequences of the Homestead Act occurred between August and November of 1890. These can be broadly classified as political songs (either campaign or protest or both), and typically dealt with persons and issues important to that year’s election. However, these are not the homesteading songs that are most often collected; the songs which have resonated most through the years are mostly those predating the volatile 1890s and which portray the universal human stories of the uncertainties of the homesteading experience. The ephemeral nature of the political songs illustrates, perhaps, the old maxim that propaganda does not endure as art, although I am not arguing that any homesteading song is fine art.

At this point, I need to define the term “folk song,” and make clear that not all the songs discussed in this article are true folk songs. I also need to explain the criteria I used to put songs into the homesteading category. For a folk song definition, I used one formulated by noted Nebraska folklorist Louise Pound, who wrote in Nebraska Folklore:

My three tests of genuine folk songs . . . have always been: they are handed down in tradition orally or in print, their form not static but continually changing; they are anonymous, their authorship and origin lost to the singers; they have retained their vitality through a fair period of time.

With this definition in mind, I began to look for songs which appear to have originated between 1854 and 1905—in other words, from the year the Kansas-Nebraska Act opened these territories to legal non-Indian settlement, to one year after the Kinkaid Act took effect. I chose the latter date to allow folk song composers ample time to respond to that land legislation. Guided by these parameters, I then looked for songs whose lyrics specifically mentioned the words such as “homestead,” “homesteading,” “soddies,” or “sodbusters,” or songs that mentioned getting land as a “claim” (e.g., “The Little Old Sod Shanty on My Claim” or “Starving to Death on a Government Claim”) and, more generally, ones in which the speaker of the lyrics is primarily engaged in farming as an occupation, even if the song did not specify the land being acquired through the Homestead Act or some other piece of federal land legislation. I found a number of songs which met one or more of these criteria; for the purposes of this article, I found that I could classify them into three categories: anthems, laments, and political songs.

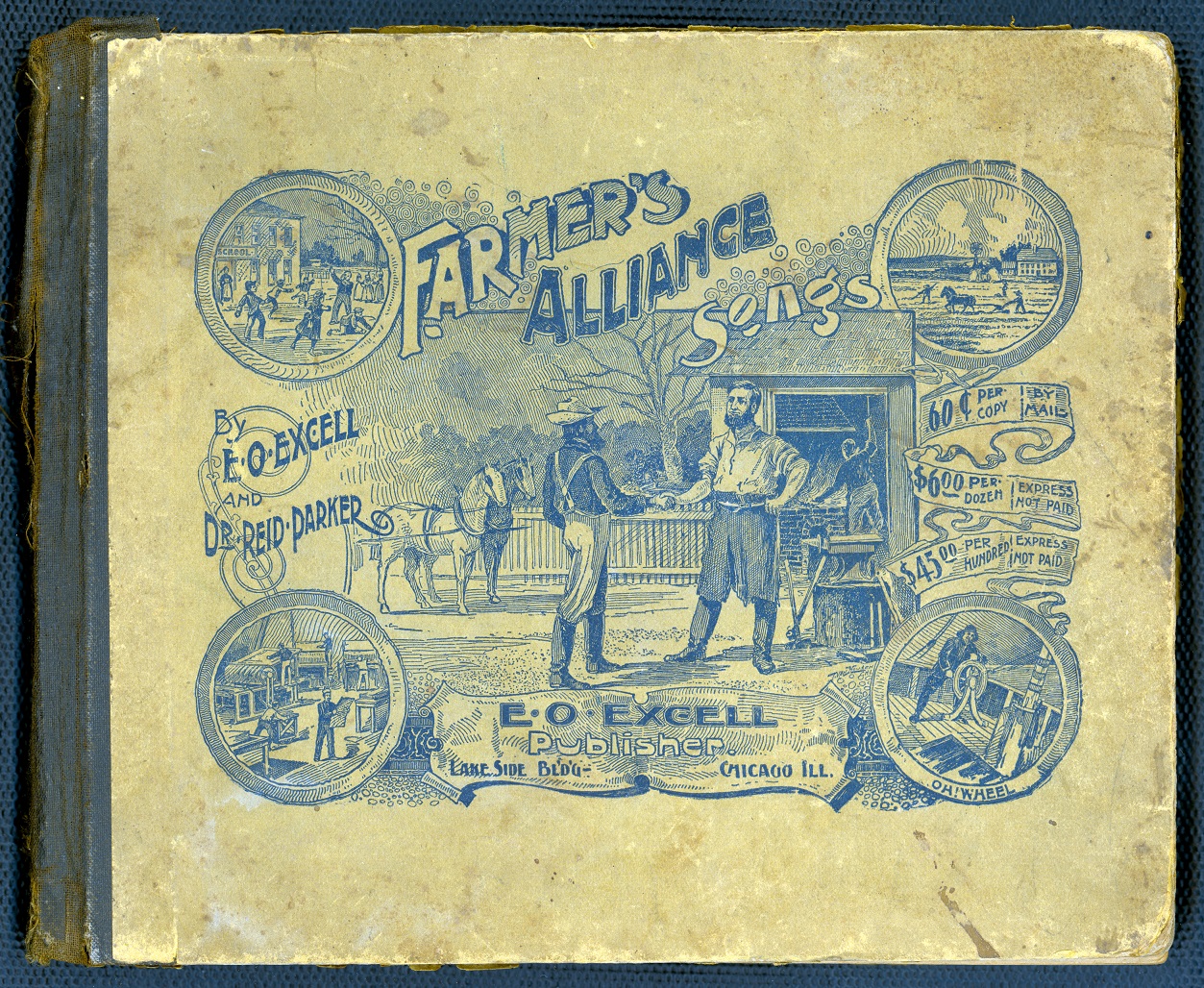

Although none of the political songs composed during the three-month deluge in 1890 is a true folk song—because its authorship is usually known or, more importantly, its vitality is gone—all of these songs drifted into the folk tradition. They drifted this way because all borrowed their melodies from older, well-known songs, which made them recognizable and easy to sing and pass along. For example, Mrs. J. T. (Luna) Kellie’s “Independent Man” was sung to the tune of “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” a popular song during the Civil War. These campaign or protest songs were ephemeral; unlike the songs I refer to as “anthems” or “laments,” only a few of the protest songs are included in the standard-bearing folk song collections.

This is an excerpt of an article that appeared in the Spring 2013 issue of Nebraska History Magazine.