To prove the strength of their controversial new building design, Behlen Manufacturing hung sixteen new International Harvester Model M tractors from the roof ridge member in June 1950. Photo courtesy of Behlen Manufacturing.

By Kylie Kinley, Assistant Editor

(Originally published August 6, 2016)

Today, a business promotion might involve a video or a hashtag. In the 1940-50s, Behlen Manufacturing suspended tractors from the ceiling and tested their buildings with an atomic bomb. Behlen Manufacturing, whose world headquarters is in Columbus, Neb., celebrated its 80th anniversary in June. The company’s huge contributions to the agriculture industry, the Columbus community, and science in general are noteworthy, but founder Walt Behlen’s sense of showmanship coupled with his mechanical genius created one of Nebraska’s better stories.

Walter Behlen grew up the second oldest of nine children on a farm ten miles north of Columbus and occupied his time raising skunks, experimenting with explosives, salvaging and rebuilding motorcycles, and creating a contraption he and his brothers called “The Crow Canon.” Behlen also saw how small and large mechanical improvements could save a farmer time and money. His father, Fred Behlen, sold the farm in the mid-1920s, and the family moved to town. Behlen had fallen ill from the Spanish influenza at age thirteen and nearly died, so he did not enroll in high school until 1925, when he was nineteen. He worked throughout high school, even holding down a full-time night job with the American Railway Express Company during his junior and senior years. He graduated at the age of twenty-three.

The family garage at the corner of 15th St. and 40th Avenue in Columbus where Walt and his family began manufacturing. RG1595-2-10

Behlen continued working at American Railway Express Company after he graduated, and he spent all his spare time working on numerous projects and inventions in his family’s garage. His ingenuity for creating equipment was remarkable – he made a “heat-treat furnace out of an old cream separator drive and other odds and ends.”[1] After a failed venture into manufacturing corn-husking hooks (mechanization made them obsolete), Behlen, and his father and brothers, who joined him in business, were successful making steel boot toe covers and metal clamps for fastening egg crates.

Behlen’s devotion to his work spilled over into his love life. When he started dating his future wife, Ruby Cumming, he sent one of his sisters to make the forty-mile trip to Fremont to pick Cumming up so he could spend another hour in his shop. Behlen later said, “Ruby soon broke me of that.”[2] He and Cumming married on April 13, 1940, when Behlen was 35. Their children later credited Ruby with Walt’s success. “Dad couldn’t have done what he did if she didn’t take care of things. She understood the business. She was never left behind,” daughter Mary Ann (Behlen) Hruska said after Ruby’s death in 2008.[3] Ruby was also responsible for all of the company’s bookkeeping in the years right after they married, and she performed these duties for free.[4]

First front of factory of the Behlen Factory, which was built in 1946 in Columbus. Photo taken in the 1950s. NSHS RG1595-2-11

Around 1943, Behlen created an invention that launched the business out of his family’s garage. He knew one of the biggest challenges for farmers was grain storage. Corn was often left in the fields to dry, putting it at the mercy of the elements. Too-wet corn stored in wooden corn cribs often grew mold or spoiled. Behlen’s solution was to create mesh wire tubes ten inches in diameter and four feet in length, and install the tubes in a corn crib. Dry air was forced through the tubes when the crib was filled. A 300-pound portable unit held ventilator tubes, a burner that used kerosene or fuel oil, and a cylindrical tractor- or motor-driven fan.[5] During the first test on June 23, 1945, the moisture content in the 700-bushel crib was reduced by ten percent.[6]

As a result of this invention, the Behlen Company’s sales reached record numbers. By August, Behlen advertised that his company would use one thousand tons of steel in 1945. In Columbus, corn ventilators stacked up in piles that nearly closed traffic on certain streets.[7] The corn dehydrators sold so well that the machines were back-ordered by September 1946 and the Behlen work force increased to more than a hundred workers who made the machines on a three-shift, twenty-four-hour-a-day rotation.

Later that year, Behlen invented a self-framed corrugated steel mesh panel farm gate that became a best seller. One day Behlen looked a pile of finished gates and decided to use the method to create better corn cribs.[8] Also in 1946, Behlen Manufacturing took out a government loan of $140,000 and built a new plant in Columbus. The company paid off the loan in one year and starting selling its newest piece of equipment: a bolt-on auxiliary gear drive that increased a tractor’s maximum road speed from four miles per hour to fourteen. It was first widely used on the International Harvester Farmall 20 tractor.

One design that took the place of the belt pulley on the International Harvester Company Model M malfunctioned and cracked tractors in half. The company immediately recalled the parts and fixed the problem. Behlen’s scrutiny of failures was as swift as his attention to promoting his successes. Model Ms were Behlen’s chosen tractor for one of the company’s biggest publicity stunts. In 1949, Behlen invented what became the company’s most famous product, the Behlen stressed-skin monocoque building. After many experiments, the Behlens found the corrugation that would provide the most tensile strength was a 7.5-inch-deep, multiple-stepped series of bends that in profile looked like half of a honey-comb. They created the panels from a long coiled strip using a cutoff die, then fed the panels through a cold-rolling machine that created the desired corrugations. The Behlens made their own cold-rolling machine because Walt felt the ones on the market were too expensive.

But when the Behlens told outsiders that they had built a 16×20 foot building with no frame and no material heavier than 16-gauge sheet metal, no one believed it would stand. Walt wrote later that the “biggest problem with our stressed-skin building method at the outset was the inability to get structural engineers to consider it seriously.”[9] On June 22, 1950, Behlen Manufacturing opened a new 50-by-200-foot stressed-skin monocoque addition to their plant. To better prove the building’s strength, Behlen hung sixteen new International Harvester Model M tractors from the roof ridge member. The building didn’t budge.

Walt Behlen works with a tractor that has the Behlen power steering unit installed. NSHS RG1595-03-02

But hanging 64,000 pounds of tractors wasn’t a good enough test for Behlen. He kept searching for a bigger way to display the building’s strength. In the meantime, the company also started manufacturing more affordable mesh-wire welders, set a record for the largest cargo of steel ever to come to Nebraska in August 1950, and took on a U.S. Navy contract that was a financial disaster.

“For many months we produced hundreds of the crates [of welded wire anti-aircraft ammunition containers] per day – at an average net loss of approximately $1,000 each day,” Behlen wrote. “It was rather difficult for my father and my brothers and me to come to work in the morning each day with the full knowledge that when the day had ended, we would have lost another thousand dollars.”[10]

The company followed up on 1951’s failures with three new products and increased revenue due to the popularity of the Behlen frameless buildings. In 1952, Behlen created a straight-disk harrow, made a line of dryers for shelled corn and other grains, and manufactured a power-steering system for tractors: “The first Behlen power-steering units comprised a simple package that the farmer could easily install himself in the field. It included a hydraulic pump powered by the tractor engine, a hydraulic gear motor coupled into the steering wheel shaft, and the necessary hoses and fittings – all for $180.”[11] Historian William McDaniel also claims that working a tractor without power steering for a day “took the same amount of energy as that required to shovel three thousand bushels of shelled corn into a bin or pitch eighty tons of hay onto a wagon” and writes that Newsweek described the new invention as “one-finger tractor steering.”[12]

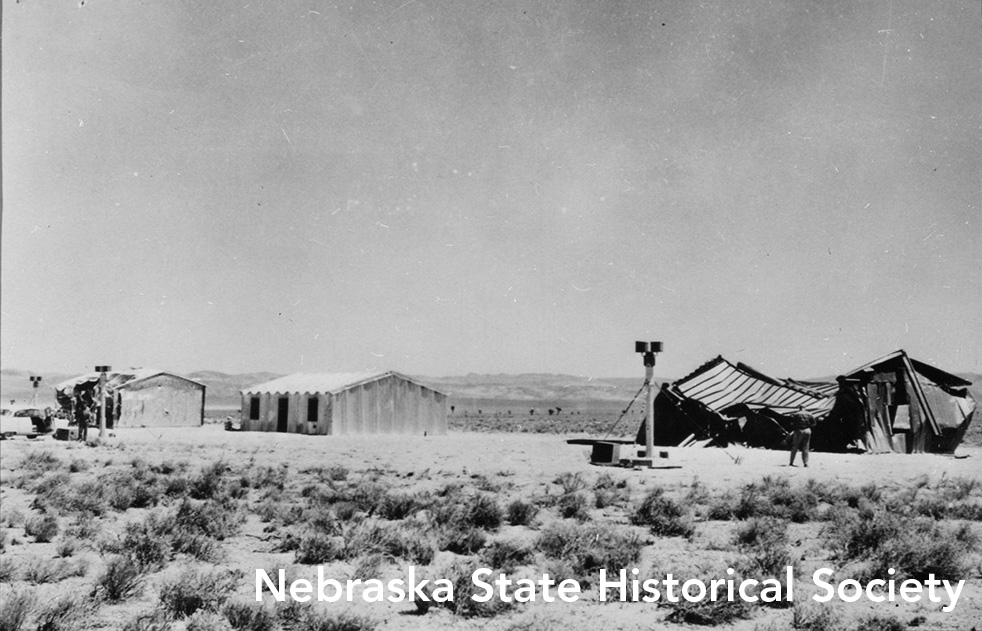

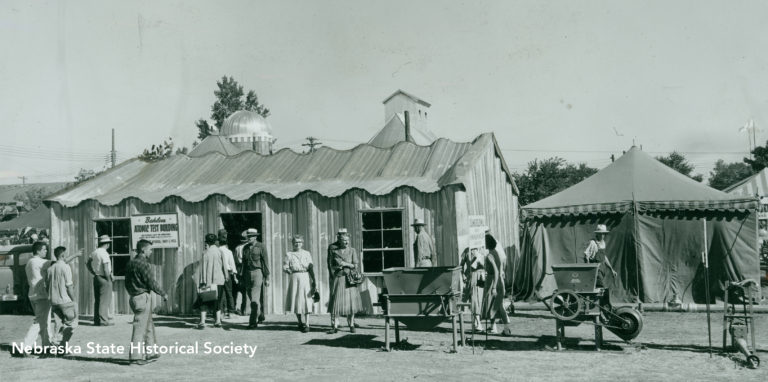

Finally, a Behlen-worthy challenge came along for Walt to test his frameless building. Behlen built two of the buildings at the Yucca Flat Atomic Energy Commission test site in Nevada. On May 5, 1955, an atomic bomb explosion released a thirty-kiloton atomic bomb (equivalent to 30,000 tons of TNT). This bomb was 50 percent more powerful than those dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. One Behlen building was 6,800 feet away from the site of the bomb detonation and the second was 15,000 feet away.

The “after” photo of the Behlen shed from the atomic bomb testing on May 5, 1955. The Behlen shed is the nearly undamaged shed in the middle.

While the atomic bomb crumpled Behlen’s competitors, their buildings stood damaged but still usable. The Behlen buildings were designed to withstand wind loads of 30 pounds per square foot. The pressure wave from the bomb blast at 6,800 feet was 600 pounds per square foot and at 15,000 feet, 250 pounds per square foot.[13] The July 1955 issue of Popular Science Monthly wrote that the building 6,800 feet away “had the front of its roof deeply dented and its sides noticeably poked; window and frames were empty and its wood door had been split into kindling. But, the building still stood firm and ready to provide shelter.”[14] The caption of the photos read, “Weird New Shed Stood Up Best.” Behlen’s flair for over-the-top publicity displays continued in October 1959 when he demonstrated the strength of a 200-foot-long Dubl-Planl roof with a live load of 289 employees.

In this 1959 photo, 289 Behlen employees serve as a live load test of a 200 ft. roof span. RG1595

Another Behlen publicity stunt flaunted the company’s wealth and power on a national level. Behlen brought $1 million worth of silver dollars from the Philadelphia mint to the 1962 World’s Fair in Seattle. There, Behlen corn cribs held the coins for public display in a frameless Behlen building. Behlen took out insurance for the transportation and display, hired guards, and took two trucks to Philadelphia to pick up the coins. Chevrolet Motor Company won the competition to provide the horsepower and provided two red tractors and red station wagons to carry the guards and Behlen company personnel. Cadillac supplied two red convertibles for the thirteen-day trip, and Trailmobile provided the tractor-trailers. Workers placed 180 cubic feet of dollars in four heavy plate steel boxes, which were specially built for the purpose at the Behlen plant. Two boxes were bolted to the floor in each of trailers above the front and rear axles. Behlen’s team loaded two hundred and fifty sacks, each containing one thousand dollars, in each box.

To make sure the public could view the coins, workers cut two holes, each about a foot square, in each tractor trailer and covered the hole with heavy plate glass and then filled the compartment behind it with coins. Then several thousand dollars were placed in a small express company “pony” safe locked with a key and chained to one of the large boxes because Walt wanted to pay expenses along the thirteen day route of the caravan in silver dollars. He bought extra dollars later in Seattle to make up the difference.

Once in Seattle, 4.25 million people passed through the Behlen building during the six months of the fair. Behlen then sold the bags of a thousand silver dollars for $1,500 each, and actually made $15,000 on the project, plus the public exposure for the company. Behlen Manufacuturing is still a successful Nebraska business under local ownership. They’ve made everything from grain bins to sports arenas to the new African Grasslands exhibit at the Henry Doorly Zoo in Omaha. One more well-known division is Behlen Country, which produces livestock handling equipment, 3-point implements, and horse and pet equipment.

The UNL Tractor Restoration Club’s shop in June 2016. On May 5, 1955, this Behlen shed survived an atomic bomb blast from 15,000 feet away with very little damage.

Both atomic bomb test buildings stand today. The building that was 6,800 feet from ground zero was a major exhibit at the Nebraska State Fair in Lincoln in September 1955 and was then was put on display by the Behlen factory. It was recently re-assembled and re-painted for the company’s 80th birthday celebration. Behlen Manufacturing donated the building that was 15,000 feet away to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and it currently houses UNL’s tractor restoration club’s shop. Looking at it, you would never guess this nondescript white corrugated steel building tucked behind the Larsen Tractor Test & Power Museum on UNL’s East Campus survived an atomic bomb blast as a publicity stunt. That’s why the other building by the factory is painted “atomic orange” which is “a brilliant crimson fluorescent paint symbolic of the heat and fury of an atomic blast.”[15] After all, nondescript wasn’t really Walt Behlen’s style.

The Behlen building that survived an atomic bomb test blast from 6,800 feet away on May 5, 1955 now sits in front of the Behlen plant in Columbus, Neb. This shed withstood pressure loads of around 600 pounds per square foot.

Works Cited McDaniel, William H. Walt Behlen’s Universe. Lincoln: Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska, 1972. Print. Griswold, Wesley S. “Atomic Ruins Reveal Survival Secrets.” Popular Science Monthly. July 1955. 49-52. Web. Sanchez, Adrian. “Ruby Behlen remembered as strong woman, loving mother.” Columbus Telegraph. 10 Feb. 2008. Web.

Behlen displayed the building that survived an atomic bomb blast from 6,800 feet at the 1955 Nebraska State Fair in Lincoln. RG1783-36-22

[1] McDaniel, 45. [2] Ibid., 41. [3] Sanchez, n.p. [4] McDaniel, 41. [5] McDaniel, 47. [6] Ibid., 49. [7] Ibid., 51. [8] McDaniel 55 [9] McDaniel, 64 [10] Ibid, 71 [11] Ibid., 77 [12] Ibid., 78. [13] McDaniel, 82. [14] Griswold, 50. [15] McDaniel 84-85