A small Lincoln community experienced a polio epidemic, but it was unclear what exactly caused the unusual outbreak. The mystery remained until a later study revealed a cringe-worthy discovery.

By Breanna Fanta, Editorial Assistant

It’s 1952: people are falling ill, some are becoming paralyzed and the community is facing an epidemic. This was Huskerville during the 1950s national polio outbreak. It was a mystery as to what caused the community’s sudden and unusual outbreak, until a study completed four years later revealed a cringe-worthy discovery.

Huskerville was a Lincoln neighborhood home to veterans, students and their families. Since the neighborhood was comprised of rows of closely spaced houses, it was assumed that the polio disease was spreading solely from person-to-person.

Families were fearful, but they had no other choice than to accept the circumstances. At the time, the public had relatively low expectations for the government to intervene in such health matters. A local pediatrician instructed the community to “live normally” and said that a majority of residents already contracted polio as it was “a common disease.”

Newspapers consistently made updates on local and state-wide polio statistics, and Huskerville proved a large contributor to Lancaster County’s number of polio cases. By the end of 1952, two Huskerville children died and 18 residents were paralyzed after contracting paralytic-polio.

In May of 1954, the University of Nebraska began testing Huskerville polio cases. They believed the residents were carriers of the disease and that by taking blood samples, they could better examine the nature of the disease spread.

That September, a new theory came to light. A mother shared with the Lincoln Sunday Journal and Star that she wasn’t concerned about contracting polio in Huskerville because she lived on a block where it wasn’t heavily contracted. This confused researchers.

A new test was then performed using a serum involving polio blood samples and in-lab cancer cells. If the virus grew on the cancer cells, it indicated that the person never had polio, but if the virus didn’t multiply, the person had contracted it.

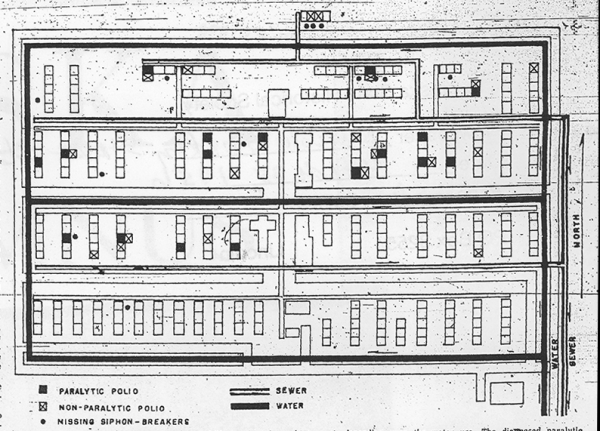

After a two year study, a sketch of Huskerville was released representing which households had diagnosis of polio and which households experienced paralytic-polio. The diagram had one telling detail though: it also indicated which houses received toilet repairs that year.

(Lincoln Sunday Journal and Star 3/25/1956)

Prior to Huskerville’s outbreak, a number of homes had improper toilet repairs. It was discovered that in some homes, a particular valve was missing that resulted in a back-siphonage of toilet bowl water into the water supply. Researchers concluded that this was the cause of the polio spread on particular blocks, but not on others. There were 13 houses missing the valve, 12 of which were on rows where high rates of polio were recorded. It was also found that while certain blocks didn’t experience high rates of polio, those residents had polio antibodies.

Following this discovery, the City Water Department regularly checked the community’s water supply.

Huskerville’s population had been declining for years and some of the temporary wartime housing was abandoned. By 1956 the neighborhood went from 3,000 residents to 900, and only 285 of the previous 800 housing units remained.

While Huskerville wasn’t the only area impacted by polio, the discovery of the outbreak’s cause makes this story unusual.

(Historical Society Collection: rg2158ph000002000020)

– Posted April 2, 2021. Marty Miller contributed research to this article.

Related:

“What happened when a million Nebraskans drank Polio Punch” [Link]

Sources:

Alliance Times, July 18, 1952

Hastings Daily Tribune, July 19, 1952

Kearney Daily Hub, July 19, 1952

Sunday Journal and Star, May 2, 1954

Sunday Journal and Star, September 26, 1954

Lincoln Journal and Star, March 25, 1956

Lincoln Sunday Star, March 25, 1956

Omaha World-Herald , March 25, 1956

Categories:

Polio, Huskerville, Lincoln