Years before the famous Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott of 1955-56, a group of Omahans led a bus boycott of their own. In this case, the target was the Omaha and Council Bluffs Street Railway Company (O&CB), which refused to hire black bus drivers. The story is part of “Mildred Brown and the De Porres Club: Collective Activism in Omaha, Nebraska’s, Near North Side, 1947-1960” by Amy Helene Forss.

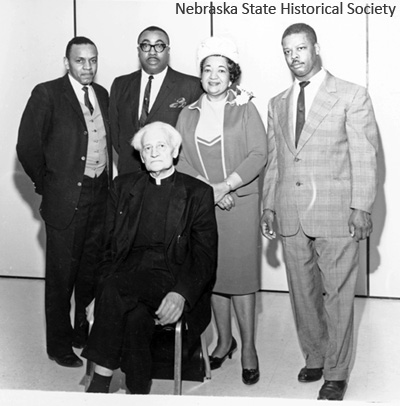

Mildred Brown (1905-1989) was the co-founder and publisher of the Omaha Star newspaper, which serves Omaha’s black community. In the 1940s and ’50s, Brown used her newspaper to challenge discrimination. She was also involved with a local group called the De Porres Club, organized by the Rev. John Markoe, S.J., a Catholic priest with a passion for civil rights. The bus boycott was but one of many initiatives led by the De Porres Club in those years.

When challenged, O&CB used stereotypical rhetoric, saying “No white woman would be safe on a street car if there was a black [man] driving.”

“The club printed and distributed pamphlets, and the Star provided irate readers with the home addresses and phone numbers of the company’s officials,” Forss writes, describing the strategy that Brown devised nearly four years before the famous Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott:

As a De Porres Club Street Railway committee member, Brown instructed her readers, “Don’t ride Omaha’s buses or streetcars. If you must ride, protest by using 18 pennies.” De Porres Club leaflets repeated her words; the club’s FBI file still contains a copy of the flyer. The club advised local merchants to stockpile pennies to aid the protestors.

As the boycott — or what ministerial activists in Philadelphia later dubbed “selective patronage”— stretched into its second year, Brown asked her subscribers to donate money to the cause. “It is obvious that we are gauged for a long campaign. A campaign of which can be won only through much hard work, planning, and finance of which must come from the Near North Side Citizenry.” In a grassroots tactic used later in Montgomery, De Porres Club participants organized carpools to keep black Omahans off the buses. Realizing the importance of communication during the boycott, Brown kept readers updated by printing the club’s daily activities.

While the Omaha protesters didn’t face the level of violence experienced by their Southern counterparts, challenging the system had its costs. Brown risked bankruptcy by angering white-owned businesses whose advertising dollars she needed, Fr. Markoe was ostracized by many of his fellow priests, and De Porres Club members found themselves labeled communists by local officials and investigated by the FBI. But the boycott was a success. After more than two years, O&CB dropped its discriminatory policy and began hiring black drivers. Many other Omaha businesses still refused to hire African Americans, but the victory was another step on a long journey.