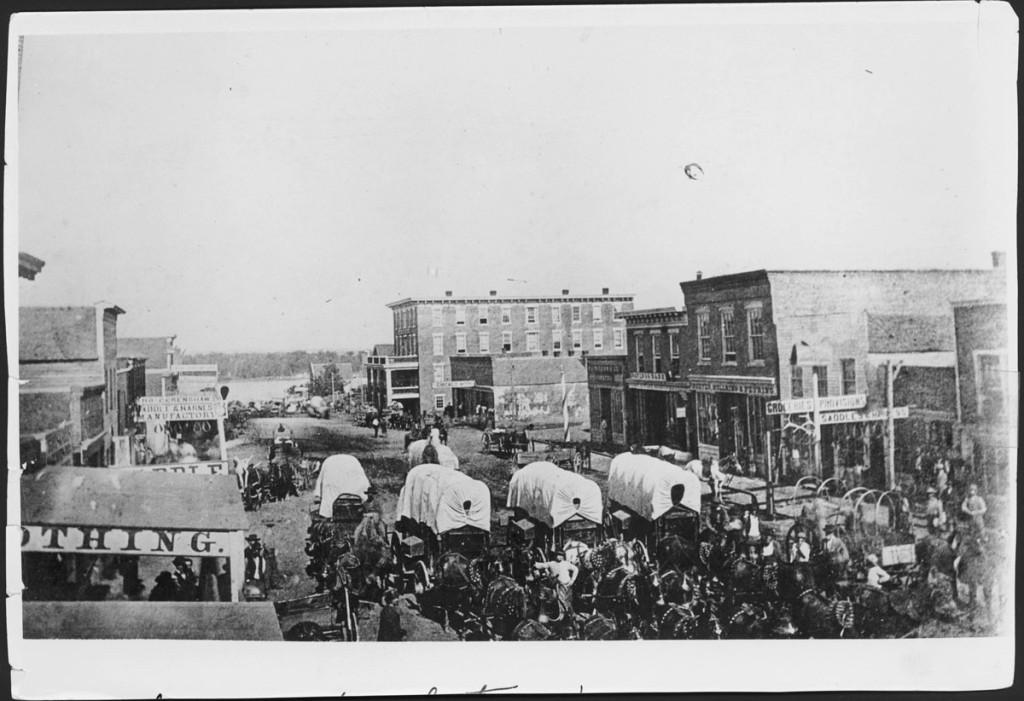

During the 1860s, Nebraska City was a major depot for freighting across the plains by both individuals and large companies. NSHS RG2294-37

During the 1860s, Nebraska City was a major depot for freighting across the plains by both individuals and large companies. NSHS RG2294-37

In 1860 James Iler of Otoe County decided to take two wagonloads of goods to Denver. Freighting to the gold mining camps in present Colorado was then a mainstay of Nebraska Territory’s economy. Iler’s wife, Sarah, and his four small children accompanied him as his wagons proceeded along the recently opened Nebraska City to Fort Kearny cutoff, a direct route from the Missouri River to the main Platte Valley trail. Near the present city of York in York County, one of his daughters fell from the wagon and was run over by the right front wheel. Iler snatched her from the ground before the rear wheel could strike her, but after some twitching, the child appeared to be dead. Iler, however, “laid her upon the ground and began pressing her breast and breathing into her nostrils, with the remark to my wife, ‘I can’t give her up,’ and after about five minutes earnest effort, she caught her breath and continued to breathe.” The family remained in camp for about two weeks while the little girl recovered. This bright outcome was soon replaced by tragedy affecting the entire family. As the Ilers were returning home, on August 9 they and four other men with wagons encountered a group of Cheyenne Indians about 150 miles east of Denver. Two of the Cheyenne offered to sell Iler a mule, which he paid for and then turned to take it away. As he reported in a September 11 letter to the Nebraska City People’s Press, one Indian slapped the mule causing it to run away. To avoid trouble, Iler said he would return the mule provided he got his money back. At that point, said Iler, several Cheyenne grew threatening and one struck at him with a club, which Iler parried. After Iler felled the Indian with a blow, others fired arrows at him. Iler then returned to his wagon after deciding to let the Indians keep both the money and the mule. “But that did not appease their thirst for blood. They came on us by the hundred, and as many as thirty or forty came close behind my wagon all shooting at once. The arrows riddled my wagon cover. By this time I had one double-barreled shot-gun loaded and turned it upon them, which caused them to leave quickly—even so quick I could not catch sight to shoot from the jolting wagon. They did not return quite so close afterwards, but from the distance would drive their arrows and rifle balls at my wagons. They shot my dog, wounded my ox, wounded me in the middle finger of my left hand, tipped me across the eyes, and set my cap a little to one side of my head with arrows, and upwards of thirty more passed not to exceed ten inches from me.” In the melee Sarah Iler was struck by an arrow that passed through her right lung, diaphragm, and liver. After Iler pointed his shotgun at them again, the Indians finally left. Finding that his wife was alive, “I availed myself of the best judgment and all the magnetic energies I was in possession of. I nursed her for upwards of twelve hours in such position as to allow the blood a chance to escape. When I thought the internal hemorrhage had ceased, I gently suspended her upon her back and constantly applied wet bandages and cold water injections.” In concluding his September 11 letter, Iler sounded an optimistic note: “I will leave the reader to his own imaginings as to our situation. Four hundred miles from the border settlements—in the midst of the Indian country—with a train of four wagons, which were our only shelter from the inclemencies of the camp life—my wife wounded almost unto death—myself only able to use but one hand and all attention to be rendered within the small space of a narrow wagon box; four little children to see to & c. &c. Well, we have passed through it all, and I feel now as though I will have strength enough to vote at the ensuing election just as usual. James Iler.” The sad final outcome was reported in the November 1, 1860, edition of the People’s Press: “You will please announce the death of Mrs. Sarah Iler, who was recently wounded by the Indians. Though her wound healed, and confident hope was entertained of her entire recovery, yet in vomiting during the fever already spoken of in your paper, her lung was ruptured at the wound, causing her death. She departed this life on the morning of the 22d inst. [October 22] at 5 o’clock, in full hope of a blissful immortality. As a wife and mother she was of excellent and rare qualities, and as a neighbor well beloved and highly esteemed. Aged 34 years, 10 months, and 10 days.” — James E. Potter, Senior Research Historian Sources: “Early Days in Nebraska,” by James Iler, NSHS Publications 4 (1892): 155-56; Nebraska City People’s Press, Oct. 11 and Nov. 1, 1860.