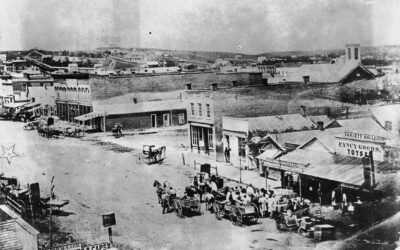

Half of a soddy, brought down by cattle after breaching the owner’s protective fencing during a blizzard many years ago.

By David Murphy, senior project architect

December 23, 2016

There are numerous reasons why the Nebraska State Historical Society is interested in recording standing sod houses, beyond the fact they are historical artifacts rapidly disappearing from the landscape. In addition to adding to the state’s archive of the historic built environment, specific questions about sod house tradition and construction are still to be answered. There is value even in recording rapidly advancing ruins, such as the one illustrated here.

In the case of this ca. 1900 sod house in central Nebraska, NSHS staff had already recorded important historical-cultural information about it with the county historical society director in 1984, including photographs and a measured floor plan. Senior project architect David Murphy and architectural historian Diane Laffin returned this December at the request of a local sod house enthusiast specifically to record sod brick dimensions and the way bricks were laid in the walls.

This set of data had newly emerged as important following work on another Society project, a collaboration with the Custer County Historical Society and others.

The re-visit also gave us more information regarding the real and potential longevity of sod buildings, and the factors that affect longevity. Earlier this year the Historic Preservation team received a request for preservation assistance regarding a sod house in rural Blaine County. One of the owners’ main questions: how long can we expect the sod house to last should we make the investment? Such a question had not been asked before, so we turned to our field work to provide some answers.

Blaine County sod house, 1984.

Same house, 2016. Cattle have rubbed through half the width of the walls or knocked them down.

Assuming the walls were competently laid in the first place, the potential longevity of a sod house is presently indeterminate; in other words, we know from the best-preserved examples that they will last for at least 120 years; but we are still counting! If key factors affecting longevity are managed, we have no reason to believe they will not last for two centuries with ordinary maintenance, perhaps longer.

There seems to be four key factors involved, given in the order of greatest negative impact first: Our subject house shows clearly how quickly livestock can destroy a soddy by rubbing against the walls. Comparing the 1984 view, when the yard was still fenced, to the 2016 view, after the fence had been breached, one can see it has taken thirty years or less for cattle to rub their way through half the width of these walls, or to have knocked them down altogether, leaving little structure left to support the roof. We know this damage was due to cattle from the smooth surfaces of the walls up to the height of a cow.

The second most detrimental impact on a sod house, like any other building, entails the loss of a weather-tight roof. The breach of the roof here no doubt helped contribute to the collapse of half the wall on the left. Once water can get to the top of a sod wall, and soak into it, the wall is doomed to failure as the material factors that hold it together begin to erode.

Standing water at the base of the walls was not an issue with this house, as its site drains away on all sides. But a lack of proper site drainage will increase and sustain moisture in the bottom of the walls, and allow freeze-thaw cycles to undermine the base by reducing wall thickness.

The relatively slight effect of long-term surface erosion is strikingly visible in the 1984 view. Eighty-five years of weathering, on a wall that had never been stuccoed, shows how well sod bricks will hold up to the natural elements. In spite of this, slow erosion does occur over long periods of time. Protective coverings of exterior walls, very commonly used in history, are ultimately an essential long-term preservation treatment.

So, to keep a soddy standing, fence the cattle out, keep a good roof on it, make sure water drains away from the building, and protect the exterior surfaces from the elements.

A precarious situation, with half of the wall worn away.