This is the second of a three-part series. The entire article appears in the Fall 2023 issue of Nebraska History Magazine. You can receive four issues a year of Nebraska History Magazine with a Household-Plus membership. Learn more here.

By William Kelly

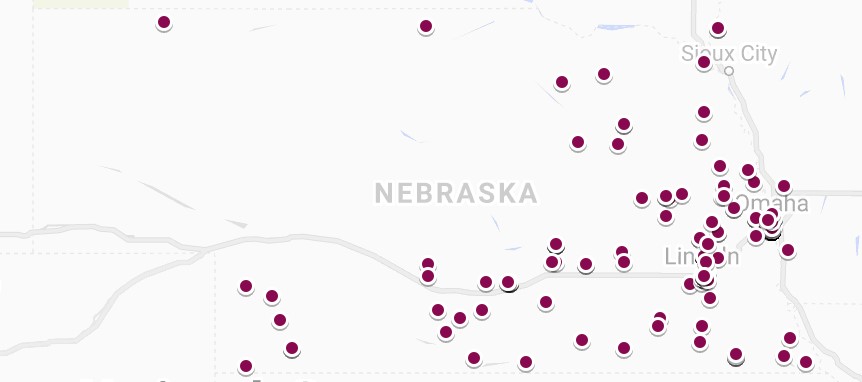

Locations in Nebraska where Displaced Persons settled after World War II. A zoomable version by the author is here: https://www.google.com/maps/d/edit?mid=1d8-X5d_kRrloTKv5fZRwRAeXHSotdY3C&usp=sharing

Displaced Persons: Where Did They Settle?

A South Omaha Case Study

Besides Jakob Drozdow, who were the other displaced persons who came to Nebraska? Where did the individuals who were, quite literally, in the same boat as Mr. Drozdow settle after the war; displaced to where? What work experience did they bring with them? Did they come with families or by themselves? Did they know someone in the United States before arriving? Or was this next chapter in their lives going to be completely new?

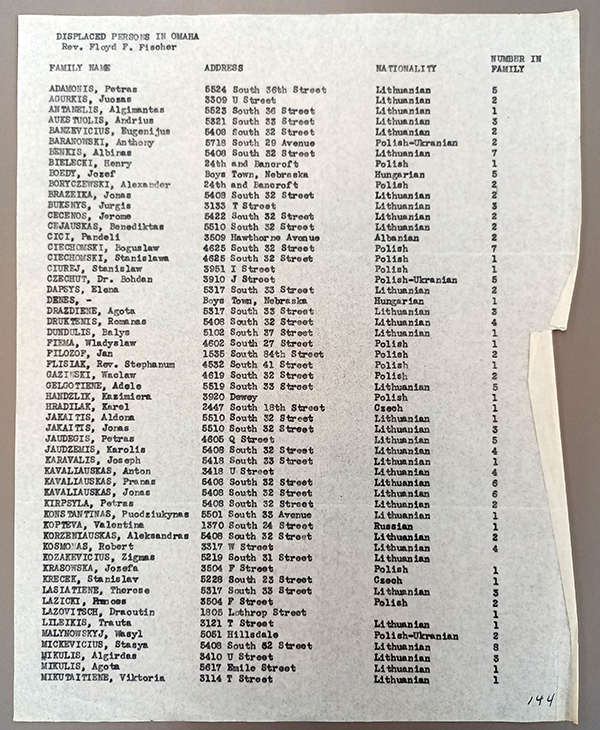

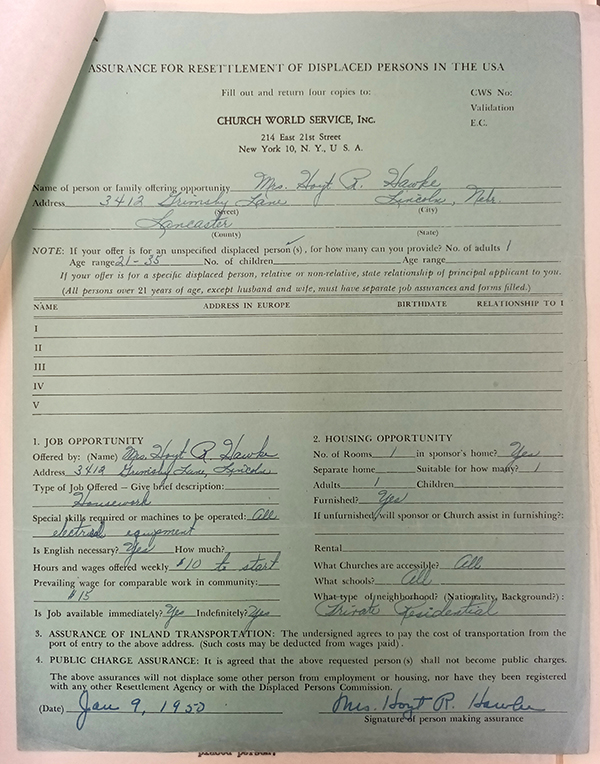

Thousands of displaced persons reached Nebraska. And we can learn quite a bit about many of them due to the registers that the Church World Service and other resettlement organizations kept. For example, ship manifests often recorded the number of displaced person(s) in a family, named at least one person from that family, identified that family’s sponsor,[1] and named the town where the displaced person(s) would live. “Displaced persons” are humanized in these documents, as we see below.

In addition to putting names to numbers, we can also use the data presented on these documents to chart the migration and settlement of displaced persons, their sponsors, and their employers in Nebraska. This sort of digital mapping enables us to ask different sets of questions about the history of displaced persons that we may not have asked before. Mapping this data helps everyone visualize the movement, lives, and history of displaced persons in Nebraska.

Figure 5 shows where displaced persons settled (represented by the blue dots) in the early- to mid-1950s in Omaha.[2] In the Google map above, we see formerly displaced persons—now settled immigrants—residing in a few areas of Omaha. Individuals and families are also scattered around the outer limits of Omaha. A Lithuanian man settled near Boys Town around West Omaha, for example. However, looking at the map, there was a large concentration of displaced person settlement in South Omaha. What does this tell us?

Zoom in on South Omaha. Because we are able to digitally represent them on this map, we can see a concentration of immigrant settlement in the neighborhoods known today as Indian Hills South and Southside Terrace.

Based on the data available to us, it seems that the primary nationality that resettled in this area through the Displaced Persons Program after World War II were Lithuanians. Other nationalities included “Polish-Ukrainians,” Croatians, and Hungarians in this small sample size.[3]

Regardless, this example of a high concentration of displaced persons’ resettlement in South Omaha especially prompts us to recall this area’s longer history of immigrant settlement. Note in Figure 5b the neighborhood directly adjacent to Indian Hills South. Social Settlement was established at the turn of the twentieth century to help immigrant families whose relatives worked in the Omaha Stockyards adjust to life in the United States. The Settlement House operated for nearly the entire twentieth century, serving working class families—immigrant and African Americans—with a focus on recreational, educational, and social opportunities. With such a service available mere blocks away, it is likely that the neighborhood of former displaced persons engaged with the Social Settlement community.

Not all records were created by the same organizations. As a result, different record keepers prioritized different information. In some documents in the History Nebraska archive, we find names and address of sponsors, businesses where displaced persons were employed, birth dates and countries of origins of displaced persons, or the name and location of the refugee camp that they stopped at on their way to the United States. Some documents have all of this information; others have only portions.

Nebraska and the National Campaign for Displaced Persons[4]

The United States was one of the last countries to pass formal legislation allowing the resettlement of Europe’s displaced persons.[5] With the U.S. eager to end its occupation of Germany and begin building a provisional government through the Marshall Plan, the federal government began expediting its efforts to relocate displaced persons.[6] Over two years after the end of hostilities, H.R. 2910, more commonly known as the Stratton Bill, was introduced in April 1947 to resettle America’s “fair share” of refugees.[7] Nebraska’s role in the resettlement of displaced persons began only after lengthy congressional debate and federal organizing largely kickstarted by the Stratton Bill.

The ensuing debate and antisemitic backlash[8] exposed the cruel underpinnings of the United States’ immigration quota system born out of the restrictive policies of the 1920s. A hollowed-out version of the Stratton Bill—now referred to as H.R. 6396— emerged after House Judiciary Committee meetings, senate debates, and congressional inaction between the spring of 1947 and the summer of 1948. This new legislation slashed the number of admissible refugees in half and created arbitrary deadlines intended to restrict the visa eligibility of Jewish displaced persons. While not explicitly anti-Semitic in language, the bill’s authors found it “more expedient and effective to craft a bill that reduced the number of Jewish immigrants by bowing to Cold War anxieties.”[9]

Then, on June 25, 1948, President Truman signed into law the Displaced Persons Act of 1948 “with very great reluctance.” In a lengthy and scathing statement, the president decried the legislation as “flagrantly discriminatory”:

“It mocks the American tradition of fair play. Unfortunately, it was not passed until the last day of the session. If I refused to sign this bill now, there would be no legislation on behalf of displaced persons until the next session of the Congress… It is a close question whether this bill is better or worse than no bill at all.”[10]

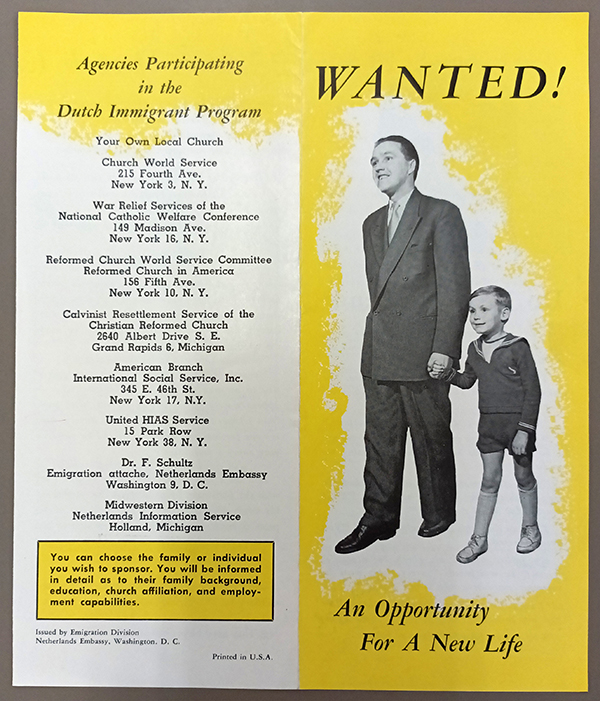

To execute the legislation as effectively as possible, President Truman appointed three men—representing the three main religious groups in the US—to lead the newly created Displaced Persons Commission.[11] The commissioners then joined forces with voluntary religious organizations to help recruit sponsors, and to obtain work and housing assurances for refugees who shared the same religious background as the voluntary organization.[12] Fearing that the antisemitic backlash towards the Stratton Bill might jeopardize the resettlement of Christian refugees, Christian organizations intensified their own public relations campaign during the late 1940s and the early 1950s.[13]

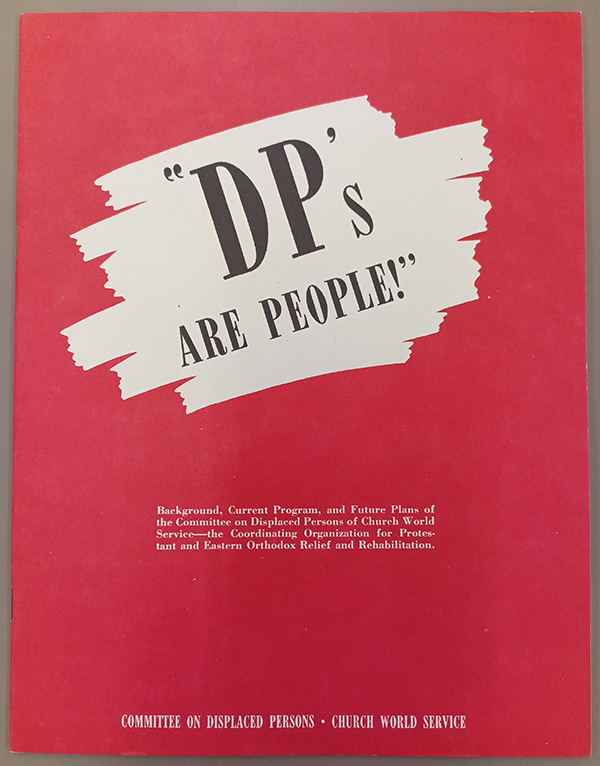

Promotional material in History Nebraska’s archives reflects the national and local trends of these organizations, including materials from one of the largest voluntary organizations working towards resettling displaced persons after 1948.

Advertising themselves as a “Protestant Program for Displaced Persons,” the Church World Service (CWS) took great pains to stress—both in language and in statistics—Protestants’ “Christian duty” to help resettle displaced persons. For the CWS, Europe’s displaced persons crisis was a “Problem for Christian People.” “The aim of the booklet is—action!” the organization proclaimed. “Because this is a great Christian, humanitarian challenge, we make no apology for this call to action in behalf of 850,000 displaced human beings, our brothers in Christ.”[14]

To succeed in the rhetorical war, voluntary organizations like the CWS emphasized the Christianity of displaced persons, while staying relatively silent about the number of non-Christian refugees. “Most of the DPs Are Christians,” one page declared. All religions and denominations are represented among the DPs. Four out of five are Christian.”[15]

The booklet’s authors were keenly aware of the dawning Cold War. “The United States has promised that none of them would be forced to go back to Soviet-dominated countries to face enslavement or death.”[16] Indeed, the fear of Communist ideology sneaking through America’s borders posed a large obstacle to each piece of legislation related to displaced persons. By painting a grim picture of freedom-loving refugees longing to escape lands now occupied by the Soviet Union, booklets published by organizations such as the Church World Service sought to persuade the public and politicians alike.

On February 4, 1948, amid congressional wrangling over federal displaced persons legislation, Nebraska Governor Val Peterson created the Nebraska Committee on Displaced Persons. Nebraska’s state level committee carried out the mission of its embryonic federal counterpart on a local level (the Displaced Persons Committee was created in June 1948).[17] The state-level committee broadcasted practical information about sponsoring a DP in Nebraska. In one packet—subtitled “Information on Refugee Resettlement under Public Law 203 as administered through cooperating Voluntary Agencies”—the state informed prospective sponsors of the refugee selection process, who is qualified to be a sponsor, what are the responsibilities of a sponsor, how long a sponsoring commitment lasts, and how much such a commitment costs.[18] This state-level material helped recruit sponsors as well as cultivate a positive public opinion towards displaced persons resettlement.

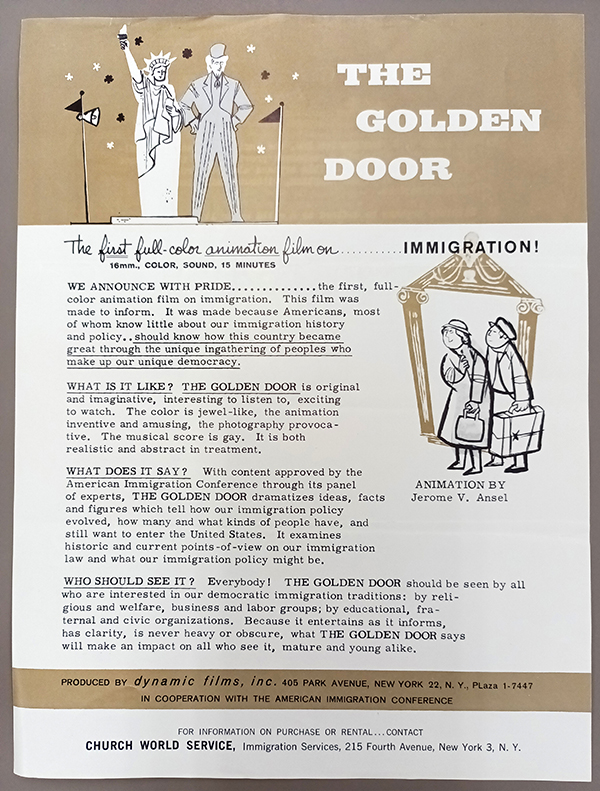

Through pamphlets, films, and radio programs the governor’s committee outlined how Nebraskans could help resettle displaced persons and allayed Nebraskans’ fears about what potential influx of immigrants might mean for U.S.-born labor. The state committee’s promotional material made sure to detail certain protections for Americans embedded within federal legislation. In fact, the Displaced Persons Act of 1948 implemented a system of assurances to prevent any “displacement of American citizens.”[19]

In order to operate effectively across the state, Nebraska’s thirty-member committee on displaced persons (composed of five women and twenty-five men largely from Omaha, Lincoln, Grand Island, and Scottsbluff) were broken down into sub-committees. The “Church Survey Sub-Committee,” for example, circulated questionnaires and promotional material to around 2,000 church communities across Nebraska.[20]

The Nebraska Committee on Displaced Persons and their sectarian partners also disseminated audio and visual material. Short educational films, such as The Golden Door and Passport to Nowhere, promoted the resettlement cause by detailing U.S. immigration policy and depicting the plight of displaced persons. The Golden Door, in particular, “was made because Americans, most of whom know little about our immigration history and policy… should know how this country became great through the unique ingathering of peoples who make up our unique democracy [original emphasis].” Other films, such as The Search, depicted portrayed displaced persons as freedom-loving, Soviet-hating, and fiercely anti-Communist. Released in 1948, The Search cast a blond-haired, blue-eyed Czech boy as the representative of all displaced persons across Europe. Films like The Search illustrated the strategies necessary to pass a DP bill after World War II and at the dawn of the Cold War. Special screenings were even organized for members of congress.[21] Radio programs sought to accomplish the same goal. The Arrival of Delayed Pilgrims was both a film and a 30-minute radio program that included interviews of displaced persons. Plymouth Rock 1949 was advertised as a 15-minute “musical cantata” on immigration. And the presidents of the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations attempted to clarify the labor aspects of displaced persons resettlement in a radio program, “Joseph in America.”[22] State, federal, and religious agencies participated in a multi-media campaign to change legislation and advocate for the resettlement of displaced persons.

History Nebraska does not possess every single type of material related to the resettlement of displaced persons after World War II. As historian David Nasaw notes in his recent book, The Last Million, Jewish organizations were vital in resettling Jewish immigrants, who were often ignored or written out of displaced persons legislation in many Western countries. Throughout 1947, for example, “Jewish organizations and the Citizens Committee had succeeded in placing the future of the displaced persons on the national agenda and shifted public opinion in their favor, as evidenced by letters to editors and congressmen, newspaper editorials, and endorsements from major labor unions and dozens of religious, women’s social, civic, educational, and ethnic organizations.”[23] Lead by Louis B. Finkelstein of Lincoln, the Jewish Welfare Society did operate in Nebraska and sat on the Committee on Resettlement of Displaced Persons. But not enough information exists in HN’s collection at this time to fully illustrate the efforts of Jewish-led organizations in Nebraska. Discovering the extent of Jewish resettlement in Nebraska would add further depth to our understanding of resettlement patterns.

There is little to suggest that the Nebraska Committee on Displaced Persons was unique in its effort to resettled displaced persons after World War II.[24] However, these promotional materials help us understand just how Nebraska fit in to the broader international, national, state, and local trends of displaced persons resettlement. Combining this information with individual stories of displaced persons and the mapping of resettlement patterns across the state begins to provide a more complete comprehension of the history of displaced persons in Nebraska.

About the author: William Kelly is a PhD candidate at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Department of History. Kelly completed this project as a graduate research assistant at History Nebraska; the UNL history department provides an assistantship in which a doctoral student conducts research under the supervision of Nebraska History Magazine’s editor.

Notes

[1] That is, the individual based in the United States that would provide work and lodging for the displaced persons.

[2] Address information was taken primarily from ship manifests that listed the address, such as the documents pictured here. If such addresses were not available, address information was taken from records that listed the displaced persons’ sponsor’s address. These distinctions should be clear in the online version of the map at [URL], specifically in the pop-up bubble that appears when one clicks on a blue dot.

[3] “The 50 percent preference for persons from ‘annexed’ countries was another deliberately and visibly anti-Communist measure designed to reward Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian, and Ukrainian DPs who had demonstrated their opposition to Communism in refusing to be repatriated to Soviet-dominated or -annexed nations. The 50 percent preference for ‘agricultural laborers’ could also be defended as an anti-Communist measure, as it brought farmers into the nation – and everyone knew that Communism was an urban, not a rural, disease.” See David Nasaw, The Last Million: Europe’s Displaced Persons from World War to Cold War (New York: Penguin, 2020), 410-411.

[4] Nebraska Committee on the Resettlement of Displaced Persons (hereafter, NCRDP), collection within the Papers of Gov. Val Peterson, RG1: SG33, Series 16, History Nebraska.

[5] Nasaw, Last Million, 11, 294-295. To be sure, Jewish organizations in the United States had been fundraising and advocating for refugee relief since the end of the war, an effort which is juxtaposed against federal government policy that skewed towards antisemitism. Jewish efforts to aid refugees were not monolithic. Some campaigned for the establishment of a Jewish state in British Mandated Palestine. Others organized a non-sectarian Citizens Committee on Displaced Persons, which was framed as an “American” effort, not a Jewish one.

[6] Nasaw, 327-328.

[7] Named after Congressman William Stratton of Illinois, this bill was crafted by the Citizens Committee on Displaced Persons and the American Jewish Conference. It aimed to resettle around 100,000 refugees per year over four years. Nasaw describes Stratton as “thirty-two years old and totally unprepared to enter into rhetorical battle with the bill’s opponents.” Aiding Stratton was the more experienced Representative Emanuel Celler of Brooklyn. See, Nasaw, 304-313.

[8] See Nasaw, 300-315, among many other examples. “It was clear from the opening bell of the second session [of the 80th Congress in 1948] that the major impediment to passing a displaced persons bill was the perception that it was a ‘Jewish’ initiative that would precipitate an invasion of Eastern European Jews” (322). With the Stratton Bill unlikely to pass for this reason, Catholic organizations began campaigning to “convince wary congressmen that the proposed legislation was not going to result in the immigration of a disproportionate number of Jewish DPs” (323). Thus, more promotional material appeared that framed the DP situation as a “Christian problem” (323).

[9] Nasaw, 323-324, 409-411.

[10] Harry S. Truman, Statement by the President Upon Signing the Displaced Persons Act Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/232598

[11] Nasaw, 410-411; 441. “The 50 percent preference for persons from ‘annexed’ countries was another deliberately and visibly anti-Communist measure designed to reward Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian, and Ukrainian DPs who had demonstrated their opposition to Communism in refusing to be repatriated to Soviet-dominated or -annexed nations. The 50 percent preference for ‘agricultural laborers’ could also be defended as an anti-Communist measure, as it brought farmers into the nation – and everyone knew that Communism was an urban, not a rural, disease” (410-411). Truman tried, but failed, to get the bill amended in a special session in July. The president then requested $2 million to set up a Displaced Persons Commission and appointed three commissioners: Ugo Carusi (Protestant, former U.S. commissioner on immigration); Edward O’Connor (Catholic, former director of War Relief Services of the National Catholic Welfare Conference); and Harry Rosenfield (Jew, delegate to UN Economic and Social Council). According to Nasaw, the new commissioners realized the new DP legislation was flawed and sloppy. There were not enough eligible DPs from annexed nations to make up the 40 percent requirement, nor were there enough farmers to make up the 30 percent requirement. (Nasaw, 441.)

[12] Commissioners “delegated the work of securing sponsors and assurances to a selected group of voluntary organizations.” The Church World Service and the Lutheran Resettlement Service resettled Protestant and Eastern Orthodox refugees. The National Catholic Resettlement Council resettled Catholic refugees. And the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society and The United Service for New Americans (USNA) resettled Jewish refugees. Each organization worked with smaller, locally based ethnic and national societies.

[13] Nasaw, 323-324.

[14] “DP’s Are People!” Committee on Displaced Persons – Church World Service, NCRDP, Box 125, Folder 7.

[15] A table in DP’s Are People! shows that of 1,447 DPs, 704 identified as Orthodox Christians, 468 as Evangelical and Lutheran, 80 as Protestant (denominations not specified), 67 as Catholic, 63 as Baptist, 31 other Christian denominations, 11 Jewish, and 1 “Mohammedan” (Muslim). “Who Are These DP’s?” in “DP’s Are People!” Committee on Displaced Persons – Church World Service, NCRDP, Box 125, Folder 7.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Part of this mission would later include sharing information about Nebraska’s displaced persons with the CIA. “Report of Nebraska Committee on Displaced Persons,” NCRDP, Box 125, Folder 1; Memo from Ugo Carusi to “All State Commissions and Committees and Voluntary Agencies,” Dec. 21, 1950, NCRDP, Box 125, Folder 1.

[18] “State of Nebraska: Governor’s Committee To Assist With The Refugee Relief Act: Information on Refugee Resettlement under Public Law 203 as administered through cooperating Voluntary Agencies,” NCRDP, Box 125, Folder 7.

[19] Ibid. Governor Val Peterson appointed “this voluntary committee…on February 4, 1948, for the purpose of studying the needs and desires of the citizens of the state on the receiving of Displaced Persons when and if federal legislation was passed permitting the immigration of individuals now in the Displaced Persons Camps of Europe, and to advise the Governor of these findings.”

[20] Other committees included the Industrial Survey Sub-Committee, the Agricultural Survey Sub-Committee, and the General Information Sub-Committee. Each was formed in the spring of 1948. “Report of Nebraska Committee on Displaced Persons,” NCRDP, Box 125, Folder 1.

[21] Nasaw, 325.

[22] Letter from Citizens Committee on Displaced Persons, “To Cooperating Organizations, Local Citizens Committees, and Friends of the Citizens Committee on Displaced Persons,” Jan. 27, 1949, NCRDP, Box 125, Folder 1.

[23] Nasaw, 314.

[24] Other states organized their own governors’ committee on displaced persons. Some general documents from these states reside in History Nebraska’s collections. See, for example, Letter from Jay L. Roney, Chairman of the State of South Dakota Committee on Resettlement of Displaced Persons, March 2, 1948, NCRDP, Box 125, Folder 1.