This article appears in the Winter 2023 issue of Nebraska History Magazine, a quarterly publication of History Nebraska. Family-plus members receive four issues per year. The print layout (PDF) of this article, with additional photos, is posted here.

By Leo Adam Biga

On their way to becoming New Hollywood icons, filmmakers Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas, cinematographer Bill Butler, and actors Robert Duvall and James Caan made a road movie together, The Rain People, that brought them to western Nebraska for the last four weeks of shooting in 1968. Their shared experience in that roughhewn locale far outside Tinseltown ended up producing three films and informing a TV miniseries.

“The cast and crew of ‘The Rain People’ took time out from shooting in Western Nebraska to hoke up this pose near Ogallala,” the Omaha World-Herald reported on July 20, 1969 (the same day as the Apollo 11 moon landing). “Surrounding the police motorcycle are Robert Duvall, learning on it at left, Shirley Knight and James Caan, standing and kneeling on it, and Marya Zimmett, perching in front of it. Director Francis Ford Coppola, with dark hair, dark glasses and dark coat, sits atop a ladder to the right with a script in his hand.” The original caption did not mention the young man behind Shirley Knight; standing atop the van while cradling a camera is future Star Wars director George Lucas. American Zoetrope

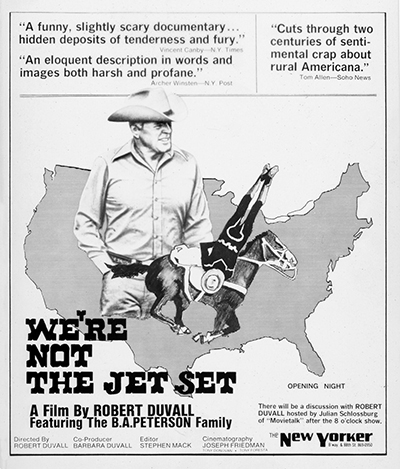

The Peterson and Haythorn ranch families befriended the actors and crewmembers during their Sandhills stay, and were memorialized in the process. Ogallala became a second home to the visitors, who rode the families’ horses and immersed themselves in their cowboy life. Duvall and Caan participated in trail drives, ropings, and brandings that strengthened their love of the West. Duvall returned several times to capture footage for his 1977 feature documentary about the Petersons, We’re Not the Jet Set. In the course of making his raw doc, Duvall grew close to that trick riding, Wild West show family.

Friendships forged during the making of The Rain People influenced artists’ individual careers and the New Hollywood in which they soon became major players. Coppola and Lucas soon formed their independent American Zoetrope production company in San Francisco, where Rain People was edited by frequent Coppola collaborator Barry Malkin. Released in 1969, the movie became the first Zoetrope imprint for Coppola’s eventual run of classics.

The arthouse film opened to mixed reviews and little business. As happens with many quirky, low-budget pics, it got lost in transition from one studio regime (Warner Bros.) to another, said its star, Shirley Knight. It did, however, win the grand prize and best director awards at the San Sebastián Film Festival. Pauline Kael’s assessment summed up the consensus: “There’s a prodigious amount of talent in Francis Ford Coppola’s unusual, little-seen film, but the writer-director applies his craftsmanship with undue solemnity to material that suggests a gifted college student’s imitation of early Tennessee Williams.”

Ripple Effects

Duvall recalled the ripple effects of making the movie: “It was a memorable time working there for those weeks there in Nebraska. It was great. It was a nice movie to work on. That’s when Coppola was doing those smaller films, before he did The Godfather and everything. It was a stepping stone to other things.”

Over time, Rain People has earned a reputation as a bold-if-uneven early work by an American cinema great. It has become part of TCM’s library of classic films, where it has gained wide viewership after being little seen in theaters.

Coppola went on to produce the first two features directed by Lucas, THX 1138 (1971) and American Graffiti (1973). The latter kicked off a nostalgia craze. Coppola, already a Best Original Screenplay Oscar-winner for Patton (1970), broke through as a director in spectacular fashion with The Godfather (1972). He cemented his status with The Conversation and The Godfather Part II in 1974. Lucas soon surpassed him, commercially speaking, with the phenomenon of Star Wars (1977) and the ensuing movie franchise, special effects, and merchandising that made science fiction/fantasy fare big commerce.

It’s no coincidence Duvall starred in THX 1138 and co-starred in the first two Godfather films, The Conversation, and Apocalypse Now, said Butler. The same goes for Caan appearing in the original Godfather and the later Coppola film Gardens of Stone. Through the experience of Rain People, Butler said, they “got into that circle” with those filmmakers.

“George got to meet Bobby and knew he should be in THX 1138,” Coppola confirmed.

It worked that way for Butler, too, William Friedkin, with whom Butler shot documentaries in Chicago, recommended him to Coppola, who liked Butler’s work so much on Rain People he hired him to do second unit photography on The Godfather and to replace Haskell Wexler on The Conversation.

Butler recalled Coppola being the same person from obscurity to celebrity, “like a big teddy bear daddy.”

“You respect someone like that for all of his talent—this brilliant person who’s a better writer maybe than he is a director, and he’s a great director,” Butler said. “But he’s like a father and he uses the same people over and over again. He used me three times and offered me pictures I didn’t take for stupid reasons.”

Caan and Duvall knew each other before Rain People from acting together in Robert Altman’s Countdown. In addition to The Godfather, they later worked together in Sam Peckinpah’s The Killer Elite.

“Jimmy’s great to work with. He gets restless though,” Duvall said of Caan, who returned the compliment, saying of Duvall, “I don’t think there’s anyone more giving than him working on camera.”

“Blatant honesty” was the secret to their friendship, Caan said. And a shared love of the West and horses.

“It was a kind of freedom and not so involved in being all withdrawn and letting the job overtake your entire life. It didn’t mean we didn’t work, but we had a lot of fun. Bobby’s a terrible practical joker. We were already goofing on each other. He’s my best friend.”

The actors’ charms won over Coppola. “I liked working with them very much, and yes, they were on all the early lists of names for The Godfather,” he said.

Duvall remembered Coppola as “a very serious preoccupied guy.” “I was more into Coppola on The Godfather, when the studio was against him. I gained a lot of respect for him. It was his picture. He was the one who made that film work. He had a lot on his plate.” The loyalty Coppola showed to Duvall, Caan, and Butler extended to other Rain People team members, especially George Lucas and Mona Skager.

“George was, and still is, like a younger brother to me,” Coppola said. “I knew early on he was a great talent, and though a different personality to my own, very helpful and stimulating to me. He’s a fine, very generous person, so bright and talented. I am very proud of him. Mona was the first ‘key associate’ I had, starting out as a secretary and blossoming into an all-around associate in the entire process.”

Both Lucas and Skager were part of the formation of American Zoetrope. “It merely took many of the ideas of a creative entity that attempted to create art works with its own means. George was essentially a co-founder, and Mona was what they called in those days the ‘Girl Friday’—today a production supervisor, involved in all we were trying to do.”

In 1968, no one imagined that they would go from fringe-dwellers to industry leaders in such a short span. That their creative convergence and ascendance intersected with Nebraska adds resonance to their story and represents a distinct chapter in the state’s little-known but rich cinema heritage. Indeed, many world-class film talents have originated here and/or come here over time (see sidebar).

Coppola and Lucas epitomized a new breed of directors from film schools (Coppola from UCLA and Lucas from USC). These counter-culture rebels with long hair and beards looked to disrupt the staid old studio system with an American New Wave aesthetic that valued independence from conformity.

Lucas was a Coppola protégé then, mainly on hand to document the making of Rain People. His resulting documentary, Filmmaker: A Diary by George Lucas, focuses on Coppola, then a rising contract talent at Warner, as he juggled the pic’s creative process, personalities, and locations. The Lucas film, filled with behind-the-scenes vignettes with cast and crew, is available on streaming services.

Said Coppola, “George’s film is excellent, if I may say, and he caught the spirit of this exciting trip, which for us was an adventure into filmmaking.”

The actors could hardly miss Lucas. “He wore a big harness and had a 16-millimeter camera strapped to his chest,” Caan said. “I thought he was born with it or something because I never saw him without it.”

Duvall recalled the future cinema titan as “a nice, quiet kind of private guy,” adding, “The documentary is as interesting as the movie.”

Recalled Knight, “Francis asked, ‘Do you mind if this kid comes along?’ And I said of course not, the more the merrier. I thought he was adorable. I could have been Miss Grand Dame and said, No. But as I always say, ‘Be nice to everybody. You don’t know, because that assistant could turn out to be George Lucas.’”

Coppola, a former college theater major, set up extensive rehearsals in New York before the trek, a practice he followed for every film after it.

“Before I even had the money or arrangement to make The Rain People,” Coppola said, “George Lucas and I went east and shot some ‘second unit’ footage at a football game and different images.” In the Lucas doc, Coppola reveals he invested his own money in the project. Once the studio came through, he was forced by the guilds to hire crew he didn’t want or need. In the doc he expresses frustration with the strictures of the establishment movie industry.

The actors who became identified with Coppola were familiar faces from television and movies, but neither Duvall nor Caan was yet established. Indeed, Knight, twice Oscar-nominated then, was the biggest name. Coppola wrote Rain People expressly for her after meeting her at the Cannes Film Festival. He was there with his 1966 film You’re a Big Boy Now and she was there with Dutchman, which she produced and starred in.

The Rain People

Rain People centers on Knight’s character Natalie Ravenna, a pregnant Long Island suburban housewife who flees her conventional life for a road spree. She forms relationships with two men on her odyssey, a brain-damaged ex-football player, Jimmy “Killer” Kilgannon (Caan), and Gordon, a Harley-driving highway motorcycle cop (Duvall).

“I was excited about this new young filmmaker,” Knight said of Coppola. “I responded to the character and to the idea we were going to make a film where we weren’t restricted. I had done a lot of films basically either on the Warner’s ranch or backlot, so I loved the idea we were going to make a film where we were at liberty to do what we wanted, to drive here and drive there. I loved that aspect of his creativity.”

Rip Torn was originally cast as Gordon. Torn, Knight, and Caan rehearsed for weeks.

“We did a lot of work improvising and all of that when we were working on the film,” Knight said. “We were trying to write about a woman being an independent creature and trying to find herself.”

She and Caan left with the production team to follow her character’s journey, and Torn was to join them when they reached the end of her wanderings.

Caan was drawn to the freewheeling material as well.

“It was a great opportunity, a great character. Just from talking to him (Coppola) I knew he knew actors. When I started working with him I knew he was something special. The guy pretty much knew about everything. When you look from there to The Godfather and all the guys Francis hired, they became the biggest in their departments, whether Walter Murch, Gordon Willis, Dean Tavalouris. They were all pretty much found by Francis.”

Duvall may have never worked with Coppola & Co., much less met the Petersons and made We’re Not the Jet Set, if Torn hadn’t quit the production.

“Rip Torn had as part of his deal we give him the Harley motorcycle so he could learn to drive it well,” Coppola said. “We did, and he parked it in front of his house in New York City, and it was stolen. He came back to us and said it was his deal to have a Harley, so we had to buy him another. But all we could afford was a good quality secondhand one, which then he said wasn’t his deal. So when we called him to say we needed him to get his shoe and calf measured for the boots, he said, ‘That’s it!’ and quit.”

Upon replacing Torn, Duvall caught up with the company in Ogallala.

“It was a small film they’d been working on for a while. I came into it at the last minute,” he said. “I knew Jimmy and I hadn’t known Francis yet when I came in to do that. Jimmy kind of coordinated it.”

“When Bobby showed up we started having fun. He’s the funniest son of a bitch,” Caan said.

Duvall and Knight had worked together on a 1962 Naked City TV episode in which they played husband and wife. “I liked him,” said Knight, adding that when “he was thrown in the mix and eventually did the role” in the Coppola film, “it was nice—he was lovely and that all worked out fine.”

“That changed a lot of film history actually if you think about it because he started doing all that work,” she said, referring to Duvall becoming part of Coppola’s stock company of actors.

Butler worked with Torn on later pics and said the actor “kicked himself for making that stupid mistake” about the bike, thus walking away from opportunities that might have been his.

Knight enjoyed the shoot. “We had our ups and downs as one always does, especially in a long shoot, and there were times when we didn’t always agree, and that always happens. But the whole experience and the film that resulted from it was I thought very positive. The only disappointment was it didn’t get the recognition and accolades I feel it should have.”

Harley drama surfaced again, Caan said, when Duvall resisted riding it. “I told him, ‘It ain’t nothin’, I’ll teach you in three minutes.’ Well, I had to get my brother to come out and double him.” A final misadventure came in a scene requiring Duvall to ride a short distance, only it kept stalling. When he finally maneuvered the bike he no sooner got off than it collapsed to the pavement, prompting Duvall to utter an epic epithet. “Oh, man, we laughed our asses off,” Caan said.

When cast and crew showed up in Ogallala, they were tired after caravanning halfway across the country.

“We were on the road, God, for that whole picture,” Caan said. “I had really no idea where we were going from day to day. We started out in Long Island and from there we went to Virginia, down to Chattanooga, and then across the country and wound up in Ogallala. There was like eighteen of us, the crew and the actors. It was just me and Shirley Knight, so every night I’d go to a different Holiday Inn and play with the light switches. I didn’t know what to do, I was a New Yorker. It was tough but it was a good picture.”

Coppola, whose wife and children accompanied him on the sojourn, was open to the whims of the open road. “I had a complete screenplay but was prepared to make any changes if we encountered something interesting along the way. We had a route, and wasn’t sure of exact locations. But my associate Ron Colby was scouting a little ahead of us and we were in communication. Generally, I tried to shoot in sequential order, though if there was an opportunity to save money to shoot slightly out of it, I would.”

Capitalizing on things they ran across, Coppola rewrote scenes to fit actual events, such as an armed services parade in Chattanooga. On the four-month trek Coppola hired single-engine pilots to take him and crew skyward to view potential shooting locales and familiarize themselves with area history.

Upon learning of a Virginia mine cave-in, the company arrived to find families grimly, silently awaiting the trapped miners’ fate. The filmmakers opted not to shoot. “We didn’t have the guts,” Butler said.

Ogallala or Bust

Ogallala became a location “by chance,” Coppola said, “but once there we felt at home.” “There were many good places that suited our story. The people were nice. There was a nice little picnic grounds. I remember a big steak cost about $6, so we’d have barbecues. We were all happy there.”

It suited Knight. “It was kind of a relief to be in one place because we’d been driving so much so that when we finally got to Ogallala it was rather nice. My daughter came out and played with Francis’ boys.” It was almost like coming home for Knight, a Lyons, Kansas, native who maintained close friendships with high school classmates. She visited Kansas often after launching the William Inge Festival in Independence.

“I always say Midwesterners make the best people. You know, Midwesterners are very open and nice.”

By the time the film went into production she said her life mirrored that of her character, right down to being pregnant. “We were doing this film about a woman in flux. When I first read the film that wasn’t the case, but when doing the film it sort of was, not that I was her. I just think sometimes life aligns with roles you play.”

She interpreted Natalie’s adventure as “a road to discovery” emblematic of the era. “Women were coming out of the ’50s as lovely housewives in aprons into becoming independent. Natalie was caught up in that. She married young and suddenly felt she didn’t have control over her life, especially being pregnant and how that affected what her life was going to be.

“In the course of the drive she makes and meeting the two men she determines that the life she has is a good life and that she could be her own person with another person. It didn’t require to reject this lovely man she loved in order for her to become independent.”

Coppola said the film “has value, I think, beyond being an early film of mine but as one of the first films to touch on the theme of women’s liberation.”

A selection of Omaha World-Herald movie ads from the October 4, 1969, shows The Rain People’s competition, including several motion pictures now considered classics.

We’re Not the Jet Set and the Petersons

The antithesis, male patriarchy, is embodied in Jet Set and its bigger-than-life protagonist, B.A. “Bernie” Peterson. As actors attracted to anything authentic, Duvall and Caan naturally gravitated to this colorful personality and his boisterous family.

Duvall recalled meeting him. “We went to their front yard, which was on the highway, and Shelley (Peterson) was riding Rock Red, a world champion cutting horse, and we started talking with the dad, B.A., and he said, ‘Are you boys from the movie?’ ‘Yeah.’ ‘You can come on down any time you want and ride some horses—you been getting any pussy?’ All in one breath. It was so funny. And we kept going down there and we formed a nice friendship.”

Duvall and Caan got so acclimated they moved into The Lazy K motel next to the Peterson spread. They bought cowboy boots and had one of the Peterson kids, K.C., polish them. K.C. said he and his family took an instant liking to the actors. In turn, the family made quite an impression on them. “Oh, boy, very unique, a rodeo circus mentality. They were kind of an identity unto themselves even in that small community,” Duvall said. “We had good times together. You’d tell B.A. a joke and he’d laugh for five minutes. He had a great sense of humor that guy.”

Of his father, K.C. said, “Old B.A., he didn’t care what he said to anybody, he didn’t care who you were. He didn’t let us call him Daddy, you called him B.A. The film brought everything out about him.”

Coppola never forgot the Petersons. “I remember the family, and Bobby’s interest in them. He was always interested in things that were ‘real’ authentic, as opposed to the fake reality of people in movies and TV shows.” Duvall recalled Coppola’s discomfort. “I don’t think he felt he fit in there. He said, ‘The Petersons are dangerous, they kind of scare me.’ He wanted to go back to New York.” The irony amused Duvall given that Coppola went on to make “mafia movies.”

Duvall came back to begin shooting his doc in 1971 without any signed releases. “B.A. said, ‘What if I wouldn’t let you do this?’ And I said, ‘Well, what are you going to do, we figured you would,’” Duvall recalled. “No money exchanged hands because I didn’t have any money to do this. We went out six times in two years or something like that.”

Duvall captured the family as they were, a raucous, cantankerous bunch, without any adornment. Their un-PC language and behavior was offensive to many then and now, but Duvall insists he was faithful to the truth.

“We let it come from them. It’s their life. I do try to go after reality, lifelike behavior within the discipline of movie time.”

In true cinéma vérité style, Duvall said, “We just kind of plunged in.” His approach, he added, was influenced by British auteur Kenneth Loach.

K.C. Peterson said an indication of B.A.’s respect for Duvall was how much rope he gave him to show the family, warts and all, without misrepresentation or exploitation. “He trusted Bobby a lot. One thing about old B.A., he could read a person pretty good.” Besides,” K.C. said, “Bobby wasn’t going to change it, he was just going to put it out there how it was. You won’t see another film like it, it’s totally different.”

“There were some pretty rough-and-tumble people back then,” said Duvall, who in press accounts described Jet Set as “a real Western rodeo film.”

“Yeah, they were a wild group,” Caan confirmed. “They would fight in the middle of the living room, and, oh boy, I mean fistfight, and he’s [B.A.] sitting back in a chair saying, ‘Now, no hitting in the face, no hitting in the face.’ Those were the rules.”

Duvall acknowledges he influenced some events. “I wouldn’t call it a pure documentary because there were certain scenes we set up. The bathing scene where B.A. hoses his little boy and then puts him in the bath tub, that was kind of set up, but it’s what they do and so it comes out a pretty pure behavior.”

Then-New York Times reviewer Vincent Canby called Jet Set “a funny and slightly scary documentary feature with scenes of unexpected candor” and an “interesting American chronicle… that regards its subjects with a mixture of awe and admiration that is ultimately ambiguous.” At the center of the film is patriarch B.A., whom Canby described as “exceedingly self‐assured, tough and robust,” adding he “may be the last of a breed—the macho father‐figure… individualist who is a hero on the frontier and an overbearing, bigoted tyrant.”

“They broke the mold after him,” K.C. said.

Of the family and the man they all answered to, Canby wrote: “They don’t make families like that anymore, or, if they do, they don’t survive very long without the commanding presence of a patriarch like B.A.”

Kris Peterson Springer said, “It’s true to who we were. I’m in no way embarrassed or ashamed by it.”

K.C. regards it as a gift Duvall bestowed on the family, perhaps the ultimate home movie. “Oh, absolutely, who can have that? I don’t know anybody.”

Jet Set locales include the Peterson home near the South Platte River and open rangeland. Events depicted range from a Haythorn branding to a wild west show to the Nebraskaland parade in downtown North Platte to a graduation to an amateur boxing match. Rain People portrays a trailer park and sites now gone, such as the Skyline Drive-In and Reptile Ranch. A climactic house fire took place in Brule.

K.C. recalled Duvall at his family’s house “all the time.” “He stayed in the motel right next door to us. He’d bring his wife Barbara and his step-daughters and crew. My mom would have them sit own down for a meal. She’d just feed them all. Then the next thing you know Bobby would say, ‘Hey, we need to film this.’ Bobby and crew followed us everywhere. You never knew when they might turn on a camera.

“Bobby would come over in the morning and say, ‘Hey, B.A., what ya’ doin’ today?’ ‘We’re going to move some cows.’ ‘We’re going to come along and watch, is that okay?’ ‘Hell, I don’t care.’ And that’s kind of how it went. They never really scheduled anything.”

K.C. said Duvall and crew got to be such familiar presences the family lost any self-consciousness around them or the camera. After sharing so many intimate scenes together, Duvall was like a member of the family. Some Petersons even visited him on The Godfather set.

The doc’s title is from the George Jones and Tammy Wynette hit of the same name that opens and closes the film. “They gave us that song and waived the $10,000 fee,” Duvall said.

After its 1977 New York theatrical premiere and a subsequent PBS airing, Jet Set fell out of circulation when Duvall and Barbara, who produced the movie, divorced and she retained rights. At one point he prevailed on the Petersons, whom he’d given a print that they transferred to VHS, for their copy in order to make a DVD. His Butcher’s Run Films shared DVDs with a few friends, scholars, and journalists, but after disbanding, the film essentially became lost to history.

Duvall is happy the Petersons appreciate the film as a time capsule of their family and way in life.

“It’s very moving to hear that because you never know if they’re going to accept something real. Like I took one guy out to help me film, and he said, ‘You’re invading these people’s privacy.’ That was the point. I wasn’t invading to make fun, I was invading to show it as it is. And if you can’t get in there then you’re going to miss things, so we had to get in there and really rub elbows with them as we filmed.”

The Oscar-winning actor who went on direct Angelo, My Love, The Apostle, and Assassination Tango with that same sense of verisimilitude knew he was taking a risk.

“I wasn’t sure because it’s a revealing thing. I think Denny (Peterson) was a little shy about it more than the others because he’s the oldest. I think it took him a while to accept it—that I do want to participate and enjoy the idiosyncrasies and the humor without condescending to it. Just show it, flat out, and I think that’s why (filmmaker) John Cassavetes responded so strongly to the film. I mean, he really liked that film.”

Duvall would love for his film to be rediscovered. “I do care about that one. I haven’t seen it in a long time. You do it for the love of it. You gotta do certain things for the love of it and you make money on other projects you aren’t totally committed to, but then it helps you pay for those that you want to do.”

In the years immediately following their brush with Hollywood, some of the Petersons took the next logical step by putting their horsemanship skills to work on feature film, television movie, and commercial productions.

They have variously trained, wrangled, rode, and stunted on countless shoots. K.C. Peterson ended up on the Walter Hill film Geronimo: An American Legend (1993) co-starring Duvall, with whom he rekindled old times, and on The Lone Ranger (2013). Brothers K.C., Denny, and Rex Peterson all worked on Ted Kotcheff’s Winter People (1989). K.C. trained and rode the horse playing Silver in The Lone Ranger.

“They got into movies, not because of me,” Duvall said. “They totally got that on their own. K.C., Shelley, Kris and Rex—they’ve done well.”

Rex followed the Hollywood trail to California, where he was mentored by famed Hollywood trainer Glenn Randall Sr. Peterson’s credits include The Black Stallion, Far and Away, Wild Bill, The Horse Whisperer, Hidalgo, Dreamer, Flicka, Appaloosa, and Secretariat.

Not unlike Rain People leading to long professional associations, Jet Set editor Stephen Mack went on to edit all of Duvall’s feature directorial projects.

Joseph Friedman, Robert Duvall, Barbara Duvall, and Stephen Mack at 1977 New York premiere of We’re Not the Jet Set. Courtesy of Stephen Mack

The Haythorns

The Petersons were not the only unforgettable characters Duvall and Caan met in Nebraska.

“Waldo Haythorn was the other rancher out there we met. Jesus, he was a character, too,” Duvall said. “That guy and B.A. were really good friends. He (Waldo) was probably like a surrogate uncle or something to Denny Peterson. Denny felt close to him. So he felt the full impact of his dad’s death when Waldo died a few years later. We’ve been involved with some good cowboys here and there.”

In 1890, Waldo’s grandfather, Walter Haythorn, and helpers drove hundreds of head of horses from Oregon to the family ranch north of Ogallala, then to the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota. This tale as told to Duvall by Harry’s grandson Waldo became the basis for the 2006 miniseries Broken Trail, which Duvall produced and starred in.

In a strange bit of synchronicity, Duvall co-starred in an earlier miniseries, Lonesome Dove, set partly in Ogallala—another example of how he and that place seemed intertwined by fate.

The story of one of Nebraska’s great ranch families, the Haythorns, begins with Harry Haythorn. A native of England, Harry came to America as a ship stowaway who earned his keep in the galley and tending a cargo of Hereford bulls. Once docked in Galveston, Texas, he hired on as a cook with the owner of the bulls and ended up making four trips on the Old Texas Trail, two of which brought him to the Sandhills, where he settled in Ogallala—the end of that famed trail. Within two decades he built Haythorn Ranches as a leading Hereford cattle producer.

His son Harry Jr. and grandsons Walt and Waldo carried on the family business. Today, Haythorn Land & Cattle Co. is a working ranch breeding commercial Angus cattle and foundation-bred quarter horses. Waldo’s son Craig Haythorn runs the operation today.

Caan got his own indoctrination into their cowboy ways. “After hanging around with Denny [Peterson] and those guys he took me to my first branding at the Haythorn ranch in Brule [Nebraska],” Caan said, “and then from there it got in my blood.”

He recalled being put to the test. “Denny picked me up at four in the morning, threw me in a trailer and we drove out there. I tried to look as Western as I could. I even had chew in my mouth. I didn’t want to stick out like some idiot from Hollywood on this big branding. Denny and I got amongst some guys, we saddled up and rode out, they were pushing some huge herd and I just fell behind ’em yelling ‘Ha, ha, ha…’ The first few days I just wrestled these calves. A Haythorn said, ‘You guys keep a-pushing on this herd’—toward this water hole. They were going to top these other hills. A bunch of them ran off and Denny rode after them, leaving me alone with these other guys.

“I never said a word, which for me is really difficult. I just kept spittin’ and yellin’ and pushin’ the herd, and we finally got ’em to this water hole, and all of a sudden these two or three calves just bolted and ran up this steep hill, so I whirled around with these old boys looking and I just took off up the hill. I got myself in a sweat chasing one. I’d get ’em together and one would break to the left. Finally I got the two of ’em and I started driving ’em down the hill and I saw those old boys still sitting down at the water hole and one of ’em looked up and said, ‘Hey, Hollywood,’ and I swallowed my chew and went, ‘Yeah?’ ‘You can leave them go, they’ve already been branded.’ That’s the way I gave myself up I guess.

“But, boy, that was some experience. Hard work. It’s a great tradition actually. These guys come from all over, the neighboring ranchers, like the Petersons, and then all the wives, boy what a feast they put out. A spread for all the hands. Homemade pies. You name it. By four o’clock, you talk about sleep and sore. I was done, I was hurtin’ boy. It was great.”

Caan earned his bona fides as a hand. “It was really a big honor. On the fourth day they build these big catch pens in different sections and run these cattle from the different sections. And on the last day old Waldo gave me the honor of roping. You’re tied onto your saddle and rope these big old calves out of the herd and drag ’em by the pit. I was flanking ’em and spread eagling for two or three days. They (the Haythorns) bought me a nice black Stetson hat as a thank-you gift.”

The actor got serious enough about it that he later competed in Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association (PRCA) events as a tie-down and team roper, despite being contractually prohibited from doing so.

The families also initiated Duvall in cowboying, though he didn’t take it as far as Caan. “I hadn’t been on a horse in a couple years when I went up to do rope and trail up there. They’re [the Haythorns] a wonderful family, too. Not quite as wild [as the Petersons], but they have their wild side, too. Waldo, he let me use his personal horse and what a horse, my God, that horse was just… the best I’ve ever been on.”

Duvall credits early experiences in the West with shaping his appreciation for that life.

“When I was twelve-thirteen I went and spent two summers on my uncle’s ranch in northern Montana and that gave me whatever wisdom, whatever knowledge, whatever enthusiasm I had for that, and respect for that to play those characters. I don’t know if I could have ever done Augustus McCrae in Lonesome Dove if I hadn’t maybe been introduced to that way of life as a young guy. I would say that’s true. Of course, they say the hardest part of that life way back then was to get a good night’s sleep on the ground, so it wasn’t as romantic as sometimes the movies portray.”

He said his times with the Petersons and Haythorns further influenced his Western roles. “Absolutely, that helped me to play Westerns from then on out, being around those people, the real thing.” In addition to Lonesome Dove and Broken Trail, Duvall played in True Grit (1969), Lawman, Joe Kidd, The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid, Open Range, A Night in Old Mexico, and Wild Horses. He was honored with the National Cowboy Western Heritage Museum’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

The same influences held true for Caan, who said those experiences were “certainly a foundation for Comes a Horseman,” his 1981 Western with Jane Fonda and Jason Robards directed by Alan J. Pakula.

Though several characters in this unlikely Hollywood-Nebraska tale are now gone, enough remain to rekindle memories. Outliving them all will be the screen stories they had a hand in making. Bringing the story full circle, Rex Peterson is the subject of a forthcoming film, Hats, Horses and Hollywood—The Rex Peterson Story, that reunites him with Duvall and other Hollywood hands he’s worked with.

A shorter version of this article was published by Flatwater Free Press. The article is based on interviews that took place over several years, and three of the interviewees, Bill Butler, James Caan, and Shirley Knight, are since deceased. The author is seeking partners and sponsors to screen these films and host panel discussions. He can be contacted at [email protected] or 402-445-4666.

Leo Adam Biga is an Omaha-based author and journalist. He is a contributing writer for Omaha Magazine, Flatwater Free Press, New Horizons, Afro Swag, and American Theatre. The Omaha native is a 1982 University of Nebraska at Omaha graduate. In 2015 he received an international journalism grant that took him to Uganda and Rwanda, Africa, in the company of world boxing champion Terence “Bud” Crawford of Omaha. Biga’s 2016 book Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film is a compilation of his writing-reporting about the Oscar-winning filmmaker from Omaha. Biga’s book with Dr. Keith Vrbicky, Forever Grateful: The Gift of New Life from Organ Donation, published in 2023. Biga has a new book due for release in 2024.

Nebraskans in the Movies (a sidebar to the main story)

Coppola, Lucas, Duvall, Caan, et al, were neither the first nor last Hollywood figures to come to Nebraska.

Homegrown filmmaker Alexander Payne has shot all or part of five of his eight Indiewood features in-state, bringing many notables to work here: Swoosie Kurtz, Mary Kay Place, Kelly Preston, Kurtwood Smith, Burt Reynolds, Tippi Hedren, Kenneth Mars (Citizen Ruth); Matthew Broderick and Reese Witherspoon (Election); Jack Nicholson and Kathy Bates (About Schmidt); Bruce Dern, Will Forte, and Stacy Keach (Nebraska); Matt Damon and Kristen Wiig (Downsizing). Other names who’ve worked here include Spencer Tracy and Mickey Rooney (Boys Town); James L. Brooks, Debra Winger, Shirley MacLaine, and Jeff Daniels (Terms of Endearment); Sean Penn, Viggo Mortensen, David Morse, Patricia Arquette, Charles Bronson, Sandy Dennis (The Indian Runner); Patrick Swayze, Wesley Snipes and John Leguizamo (To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar); Martin Landau, Ellen Burstyn, Elizabeth Banks and Adam Scott (Lovely, Still); Jason Reitman and George Clooney (Up in the Air); the Coen Brothers (The Ballad of Buster Scruggs); and Frances McDormand (Nomadland).

Many Hollywood luminaries have visited, most memorably for back-to-back world premieres, each of which attracted tens of thousands onlookers to downtown Omaha. The first, in 1938, brought co-stars Tracy and Rooney, plus MGM brass, for a gala screening of Boys Town. The following year Cecil B. DeMille, Barbara Stanwyck, Joel McCrea and Paramount came to represent Union Pacific during Golden Spike Days. In 1941, Lincoln hosted the world premiere of Cheers for Miss Bishop, based on a novel by Nebraska author Bess Streeter Aldrich, and starring Martha Scott.

Other movie industry titans who have made their way here include: James Stewart, Otto Preminger, Joshua Logan, Alan Arkin, Patricia Neal, Ray Harryhausen, Robert Redford, Shirley Jones, Debbie Reynolds, Danny Glover, John Landis, Steven Soderbergh, Jane Fonda, David O. Russell, Julianne Moore, Paul Giamatti, and Tamara Jenkins.

Then there are the Hollywood talents Nebraska has produced, ranging from silent film star Harold Lloyd to mogul Darryl Zanuck to song and dance legend Fred Astaire. The state has given us leading men Robert Taylor, Henry Fonda, David Janssen, and Nick Nolte. Leading women Dorothy McGuire, Coleen Gray, Sandy Dennis, Marg Helgenberger, Lori Petty, Hilary Swank, Julianne Moore and Gabrielle Union have called Nebraska home. The same for character actors Inga Swenson, Ward Bond, James Coburn, John Beasley, and Yolonda Ross. Method icons Montgomery Clift and Marlon Brando hailed from here.

Nebraska is also where brothers George and Noble Johnson formed the nation’s first African American film production outfit, the Lincoln Motion Picture Company. Nebraska produced film composers Ann Ronell and Paul Williams, cinematographer Donald Thorin Sr., writer-directors Payne, Joan Micklin Silver, Gail Levin, Dan Mirvish, and Nik Fackler, producer-screenwriter Lew Hunter, producers William Dozier, Jon Bokenkamp, and Chanelle Elaine, and Oscar-winning editor Mike Hill. Nebraska is the adopted state of Oscar-winning cinematographer Mauro Fiore.

Two major art cinemas are based in the state: the Mary Riepma Ross Media Arts Center in Lincoln, and Film Streams in Omaha. These venues, together with the Omaha Film Festival, elevate the state’s cinema culture. Restored historic theaters in Omaha, Kearney, North Platte, and Scottsbluff screen classic and contemporary films.