Everyone dreams of finding buried treasure. But imagine going to your local flea market and finding a rare copy of the Declaration of Independence. That’s just what happened to Tom Lingenfelter, a rare historical documents dealer, in 1992. He paid $100 dollars for what turned out to be one of only three known “Anastatic” copies (more on that later). Another lucky treasure hunter paid $2.48 at a thrift shop for a printing that ended up fetching $475,000. Every year the Ford Center gets a handful of calls from people hoping they will get to be one of the lucky few with a genuine article. Unfortunately, the Ford Center staff is not qualified to make authentication assessments of such rare documents, but we can share some resources on where to start looking to see if what you have might be a coveted copy of our nation’s birth certificate.

The Original

First, we need to know a bit about the history of the Declaration of Independence itself. On June 7, 1776, the Continental Congress appointed a committee of five men—John Adams, Roger Sherman, Benjamin Franklin, Robert Livingston, and Thomas Jefferson—to draft a statement declaring the American Colonies independent of British rule. The text was primarily written by Jefferson with edits by Franklin and Adams, and a draft was submitted to Congress on June 28. Additional revisions were made by Congress, and the Declaration was passed on July 4. Only John Hancock, the President of the Continental Congress, and Charles Thomson, the Secretary of Congress, actually signed the Declaration on July 4, 1776. Congress immediately ordered official printings to be made and distributed to the state legislatures, committees of safety, and the commanders of the Continental army. The original manuscript from July 4th, signed by Hancock and Thomson was never seen again.

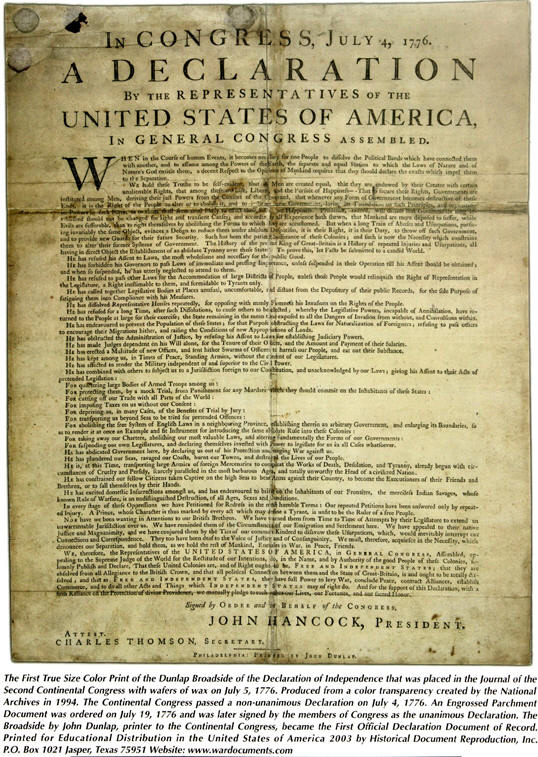

The Dunlap Copies

Philadelphia printer John Dunlap worked all night to produce approximately 200 broadsides on July 5. Only 25 Dunlap Copies are known to exist today. Dunlap Copies are typeset printings with the title, “In Congress July 4, 1776, A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America in General Congress Assembled.” At the bottom, it reads “Philadelphia: Printed by John Dunlap.”

The July 4th printing of the text of the Declaration of Independence. This was typeset using Thomas Jefferson’s original manuscript which has been lost to time.

What to look for: Measures 47 cm x 38 cm; “In Congress, July 4, 1776, A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America in General Congress Assembled” at the top and “Philadelphia: Printed by John Dunlap” at the bottom, with no signatures.

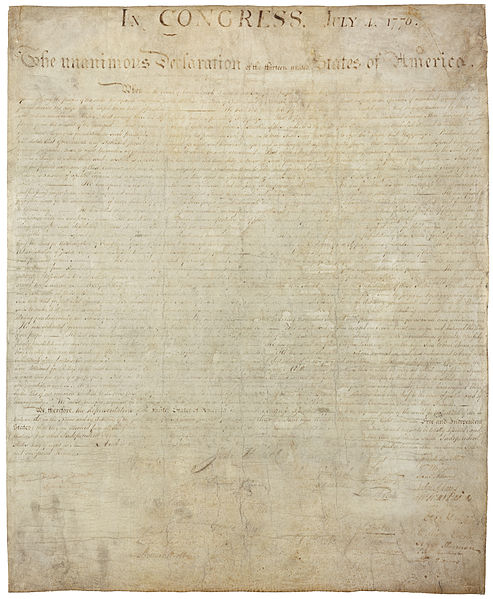

The Engrossed Copy

The official, engrossed copy of the Declaration of Independence housed in the National Archives.

It wasn’t until July 19th, 1776, that Congress ordered an official, or engrossed, copy of the Declaration on vellum. Timothy Matlack, the assistant to Charles Thomson, scribed the final document that was signed by the representatives. It is titled, “The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America.” It was printed by Mary Goddard in January 1777. The final signature was placed by Thomas McKean of Delaware possibly as late as 1781, bringing the final number of signatories to 56. This is the copy that is displayed in the National Archives, much faded from its original clarity.

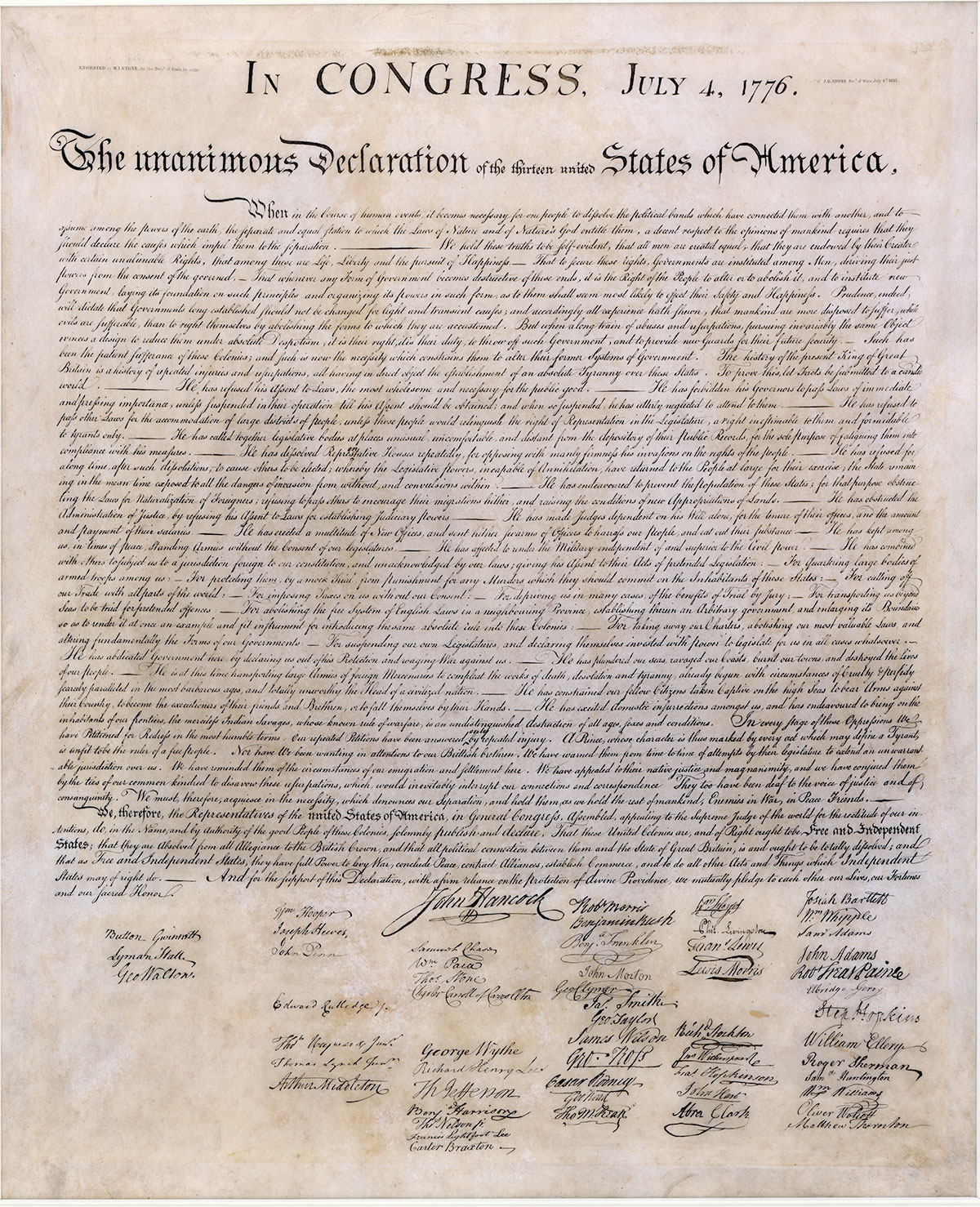

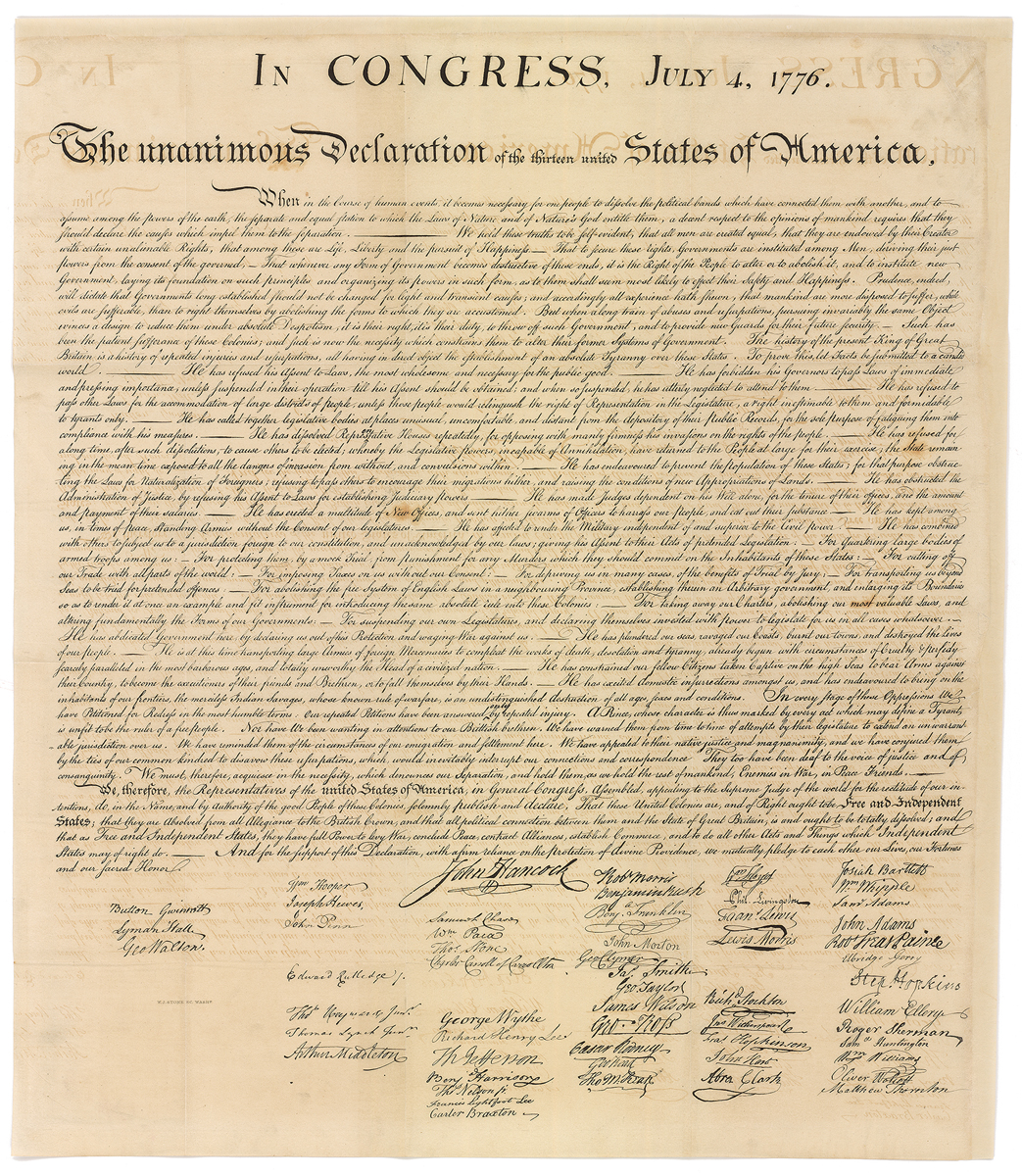

The Stone Copies

Following the War of 1812 and with the nation’s 50th birthday close at hand, John Quincy Adams commissioned a facsimile of the original engrossed copy of the Declaration to be made in 1820. Washington, D.C. engraver William Stone took three years to complete the task of engraving the copper plate. Congress passed a resolution on May 26, 1824, to produce 200 copies on vellum. These were distributed to official record repositories, elected officials, the surviving signers, and two copies were presented to the Marquis de Lafayette on this visit that year. Stone facsimiles, as they are known, are 24” x 30”. At the top reads “Engraved by W.I. STONE for the Department of State by order of J.Q. Adams Secy of State July 4, 1823.” After the 1823 printings on vellum, the imprint line was burnished off, and the line “W.J. STONE WASHN” was added to the bottom left under the signatures. Later printings on paper are the same size and are still highly prized by collectors.

Stone printed additional copies in 1833 from inclusion in Peter Force’s American Archives, 5th Series, Volume I, which was published in 1848. These prints measure 30” x 26” and have the imprint “W. J. Stone Sc Washn.” in the lower left. Facsimiles similar to the Stone printings are very common, but are substantially smaller, and have little to no historical or monetary value.

The original Stone printing of the Declaration of Independence from 1823

A later copy printed for Peter Force’s American Archives

What to look for: For the original Stone copies it will be printed on vellum, though later copies may be on paper, measuring 24” x 30”, “Engraved by W.I. STONE for the Department of State by order of J.Q. Adams Secy of State July 4, 1823” at the top. Later copies have “W.J. STONE WASHN” on the bottom left under the signatures. 1833 copies measure 30” x 26” and have the imprint “W. J. Stone Sc Washn.” in the lower left.

The Anastatic Declaration

Tom Lingenfelter’s copy of the Declaration of Independence is exceptionally rare and helps explain the deteriorated state of the engrossed Declaration in the National Archives. Lingenfelter’s copy was believed to be a memorabilia copy from the Centennial in 1876. At the bottom left he saw the words “ANASTATIC FAC-SIMILE”. Anastatic printing is a method developed in the 1840s in Germany and later in England. In anastatic printing, a chemical transfer process produces a plate from the original document or printed image. Unfortunately, the process would sometimes destroy the original. Lingenfelter believes this anastatic process lead to the near destruction of the original engrossed copy and explains why the original is so faded.

Tom Lingenfelter stands with his framed Anastatic facsimile of the Declaration of Independence.

Photo by Matt Rourke / AP.

What to look for: Measures about 25” x 30”, and the text of the document is printed handwriting as opposed to typeset. “ANASTATIC FAC-SIMILE” is printed in the bottom left.

Other collectibles and highly valuable reproductions of the Declaration of Independence exist, and it may be worth looking up collector’s websites online. However, most copies in family collections are souvenirs and commemorative copies. Even if the paper looks “really old”, it probably is not. Before 1850, paper was made by hand and of high-quality materials and was therefore very stable. From 1850 until the mid-to-late 20th century, paper began mass-produced by machine using poorer quality materials with high acid content. Thus, the older the paper is, the more stable it could be. If your copy is less than 20” tall and lacks the printer’s credit line, it probably doesn’t have a monetary value. If you still think you have something worthwhile, contact the Ford Center, and we can put you in touch with someone who can help. And even if your copy only has personal value to you and you would like help preserving it for future generations, paper conservator, Hilary LeFevere will be happy to help.