“The Most Beautiful Man in the World.” The “reincarnation” of a Greek god. A suffragette’s ideal man. “A gay camp icon.” Paul Swan embodied all these superlatives

“The Most Beautiful Man in the World.” The “reincarnation” of a Greek god.

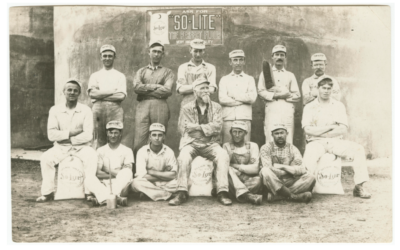

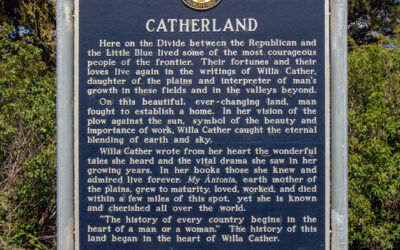

A suffragette’s ideal man. “A gay camp icon.” Paul Swan embodied all these superlatives. Raised in Crab Orchard, Nebraska, in the 1890s, Swan’s eccentricities and gender non-conformity made him an outsider. He fostered friendships with artists and intellectuals in the area, such as Willa Cather. Eventually, He studied at the Art Institute of Chicago before moving back to Crab Orchard to teach art. Wanting to try his hand at becoming “a serious artist,” he moved to New York City in the first decade of the 1900s. Despite having male lovers throughout his life, Swan married his wife Helen Gavit Swan in 1911, and they remained close until her death in 1951. They had two daughters.

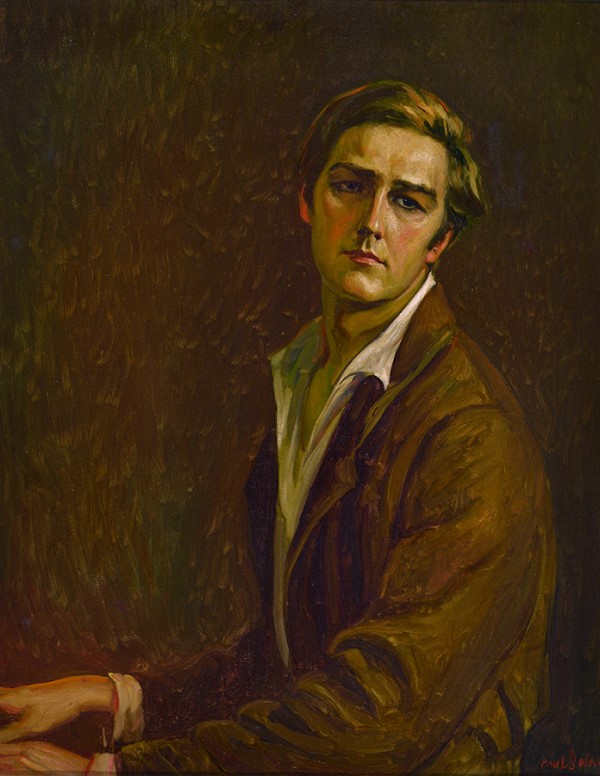

Paul Swan, Self Portrait, oil on canvas, c. 1920, Museum of Nebraska Art Collection, Gift of Dallas Jr. & Margaret Swan.

After seeing Russian actress Alla Nazimova in a play, Swan was inspired to paint her portrait. She was so pleased with his work she commissioned an additional four portraits. With the money he made from his career, he was able to travel to Egypt and Greece, where he was heralded as “the reincarnation of one of our lost gods.” A 1913 issue of the Omaha Bee holds Swan as the “Suffragette Ideal.” While in Greece, he began his career in dance which became his life-long passion though he continued to paint and sculpt.

He became friends with modern dance pioneer Isadora Duncan and painted her portrait in 1922. She dubbed him “the most beautiful man in the world.”

Swan was famous throughout the world for his artwork and his dancing. His bust of Willa Cather sits in the Nebraska Capitol Building. He appeared in Cecil B. DeMille’s 1923 film “The Ten Commandments” and other silent films. He settled in Paris in the early 1930s, but much of his artwork was lost after the Nazi occupation of Paris, which forced him to return to the US.

As times and tastes changed, Swan became less fashionable. By the 1960s, his dance performances in New York City were seen as campy. As a result, Andy Warhol included him in his film “Camp.”

Swan died in 1972 at the age of 88 and is buried in Crab Orchard.

The Ford Center has treated six works by Paul Swan over the years. Private clients own most, but the Museum of Nebraska Art owned two. The pieces were treated for an exhibit on Swan in 2016, which was the first retrospective ever held of his work. The piece described here is a plaster bust of American poet Jeanne Robert Foster. The bust is on a tall base decorated with nude figures in the Classical style.

The bust of Jeanne Robert Foster by Paul Swan, before treatment.

The bust was in good condition overall but had a thick coating of grime which gave it an overall gray color.

Testing showed that erasers and poultices could remove most of the grime.

Two cleaning tests on the back shoulder of the bust show the white plaster underneath the grime.

After this first round of cleaning, the dirt trapped in the pores of the plaster was also much more noticeable, as were dark marks that the grime had obscured.

Extensive testing using different solvents, poultices, and cleaning solutions was carried out, first on a plaster mock-up, then on multiple areas of the piece. This was necessary because there were traces of different coatings and types of residues on the surface of the bust. Some areas of the figure cleaned up easily to a bright white while others remained dark, leaving the surface of the bust with a patchy appearance.

No solution or poultice tested seemed to do a decent job without the risk of leaving residues on the surface. Additional tests were carried out on a plaster mock-up using soft air abrasive media. The surface of the bust was further cleaned using sodium bicarbonate in an air abrasive unit driven at low force at a distance of 5″ from the surface.

The bust during treatment. The image of the left shows the bust after it had been cleaned overall using eraser crumbs. Dirt and grime remain. The image on the right shows the bust after air abrasion.

Distracting dark areas that remained were gone over with a weak enzymatic solution on cotton swabs, followed by deionized water. Next, a barrier layer was applied to the most distracting dark areas that remained on the surface, such as on the woman’s chin.

These areas were toned with varnish mixed with dry pigments.

Dust from pastels was applied to the larger pores of the plaster that were still dark and distracting.

The bust’s appearance after the treatment is significantly improved and much closer to the artist’s original intention.

Once the years of surface dirt and grime had been removed, it was possible to see previously obscured details, such as casting lines on the face and the artist’s signature on the left side of the base’s front edge. Just as Paul Swan himself had faded into obscurity, his beauty was once again revealed to the world.

To learn more about Paul Swan and the 2016 exhibit of his work at MONA, visit Nebraska Stories: The Most Beautiful Man in the World.