This article appears in the Fall 2023 issue of Nebraska History Magazine. Household-plus members of History Nebraska receive four issues per year. Learn more.

By David L. Bristow and Ben Kruse

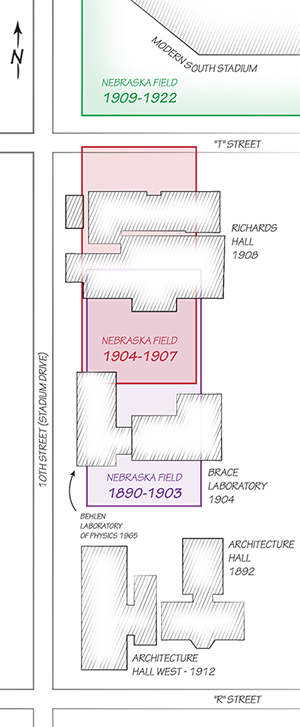

The Cornhuskers have played 100 seasons in Memorial Stadium, but it was not the first home of University of Nebraska football. In this centennial photo essay, we look back at the university’s early football fields up to the time when the present stadium was built as a memorial to the soldiers and sailors of World War I.

A group of students pooled their money to buy a football and began organizing teams in 1889. At the northwest corner of the four-block campus lay an open field where students played baseball and Lieutenant John Pershing drilled his military cadets.[1] It would be long enough for a proper football field if only a stand of trees was cut down.

But the university was less than two decades removed from its founding on a treeless prairie. The administration was not eager to see precious trees cut down. According to one story, students borrowed an axe and took matters into their own hands in a series of nighttime raids.[2]

Albert Troyer, who scored Nebraska’s first official touchdown in 1890, recalled obtaining permission to cut down “the most objectionable of the trees.” The real difficulty, he said, was that many of the young men eager to play football were a lot less eager to grub out stumps and prepare the field.[3]

The original field ran along 10th Street (now Stadium Drive) between present-day Architecture Hall and T Street. Here the first intra-mural games were played in the fall of 1889. And whether the designer of the 1970s Herbie Husker mascot was aware of it or not, NU’s first unofficial football teams played in overalls.[4]

Now they were ready to challenge other schools. Clad in new uniforms of white canvas, Nebraska played its first official two-game football season in 1890 and early 1891, defeating a YMCA team in Omaha and Doane College in Crete. Nebraska’s first home game, a victory over Doane, was played at Lincoln Park (today’s Cooper Park) on October 31, 1891.[5] The baseball park had bleachers, making it more desirable than the campus field. Nebraska played home games at Lincoln Park in 1891 and 1892, and then played at M Street Park (at 23rd and M near the present site of Lewis Ball Field) from 1893 to 1896.[6] During these early years, Nebraska also played multiple “home” games at Omaha’s YMCA Ball Park and at University Park.

Home games moved to the campus field starting in 1897 after the university built a grandstand along 10th Street. Early football was notorious for brawling, so the university put up a barbed wire fence between the bleachers and the field. At an 1899 intra-mural game, crowd control was provided by fourteen seniors armed with baseball bats. For varsity games, the university preferred to rely on the Lincoln Police Department.[7]

A few years later, the university added a high wooden fence to prevent non-paying spectators from watching the game. Even so, photos of the period show fans perched in trees and atop nearby buildings. The bleachers gradually expanded to hold several thousand spectators.

Nebraska played seven seasons on the original campus field, including a spectacular 1902 season in which the Cornhuskers went unbeaten, untied, and unscored upon in nine games.

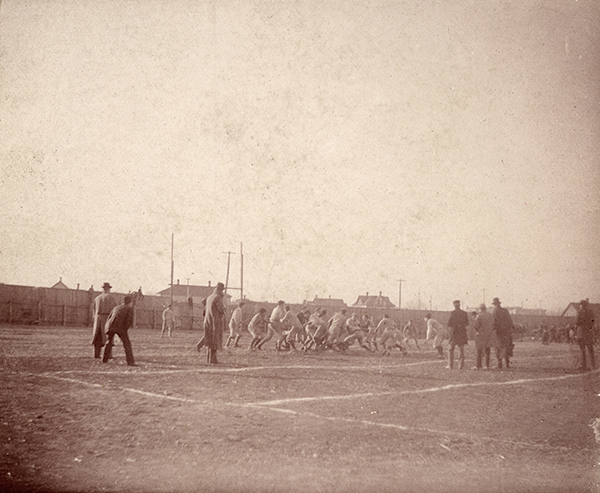

Labeled “original field,” this 1895 photo (apparently looking southwest toward 10th Street) is the earliest known action photo of University of Nebraska football, although it is probably not a varsity game. Nebraska played its home games at M Street Park 1893-1896. RG2758-105-2

Looking northeast, apparently from a rooftop on 10th Street, the original football field lay north of the 1895 library (today’s Architecture Hall). The ornate building at center is Nebraska Hall, the university’s first building. RG2758-2-12

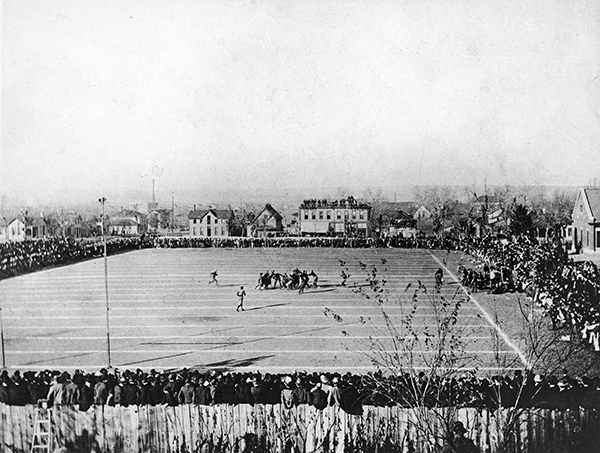

One of the earliest known photos of an NU varsity game, ca. 1897-1901, looking north from the library toward T Street. RG2758-105-5

Then in 1904 the Board of Regents threw the entire program into jeopardy.

“Shall the Athletic Field Be Sacrificed?” asked a Daily Nebraskan headline after the Regents approved the construction of a new physics laboratory on the football field.[8] The decision proved so unpopular that the Regents reconsidered, but the crowded campus had little open ground. In the end, Brace Laboratory was built on the south part of the field, and the gridiron was shifted north along 10th Street.[9]

At the time, a standard football field measured 110 yards from one goal line to the other. There were no end zones. The new south goal line lay only three yards from the blond brick wall of Brace Lab, while the north goal line lay a similar distance from a wire fence that bowed out into the middle of T Street.[10] Even so, the field was now a little shorter than standard length, and the Regents heard many complaints that its “flint-like hardness” resulted in unnecessary injuries.[11]

The 1904 Nebraska football team on the “cut-down” field. The view is to the south along 10th Street, with the new Brace Laboratory standing just beyond the goal line. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries

Starting in 1904, a corner of the south goal line was dangerously close to Brace Laboratory. Football fields did not yet have end zones. RG2758-0-72

Meanwhile, the north end of the shortened field jutted out into T Street. (Notice how the fence curves back away from the street in the background.) Here, Nebraska rolls to a 72-0 victory over Grand Island College on September 24, 1904. And if the yard lines seem to be going the wrong way, that’s because for several years in the early 1900s, football fields were marked with a crisscross (“gridiron”) pattern of lines. RG3451-3-122

The 1907 Cornhuskers. In the background is the north goal line and the neighborhood north of T Street, including S. Bowers’ grocery store in what is now the parking area behind South Stadium. RG2758-0-2136

Construction of a new engineering building (Richards Hall) took the rest of the field in 1908. The Huskers returned to M Street Park (by then known as Antelope Park) for that season’s home games.[12] Head coach William “King” Cole complained that he didn’t even have decent practice field and that “we had to go out into a cow pasture with ruts every ten feet to get a place where we could practice at all.” Even the governor complained that the situation was “a shame and a disgrace.”[13]

Just north of T Street, meanwhile, homeowners grew increasingly nervous as officials spoke of expanding the campus and convinced the legislature the give the university the power of eminent domain.[14]

The Regents made their move in the spring of 1909. For the first time—and certainly not the last—the University of Nebraska forcibly displaced a neighborhood, buying part of the land on which today’s Memorial Stadium stands.

It all happened quickly. The regents decided in April to condemn two residential blocks north of T, but then ran out of money until the head of the local streetcar company began buying lots for them. Purchases were finalized in mid-June, houses were auctioned and hauled away, and workers began filling in cellars and building bleachers. To fit its two-block space, the new Nebraska Field ran east-west instead of north-south, with the south bleachers backed up against T Street.[15]

The S. Bowers grocery in the previous photo was part of a four-block area purchased in 1909 for a new football field. Here the camera looks northwest across T Street at the newly cleared area. Houses along U Street are visible in the center-right background. Today that row of houses is more-or-less the south end zone in Memorial Stadium. RG2758-0-2138

Looking northwest toward 10th Street across Nebraska Field (1909-1922). South Stadium covers most of this ground today. Notice the fans perched on ladders, rooftops, trees, telephone poles, and the stadium awning. RG2758-105-6

That fall, the Cornhuskers returned to Antelope Park until they moved into their new home mid-season, playing Iowa to a 6-6 tie on October 23.[16] The team was already complaining about the new field’s “hard pebbly surface.” The Daily Nebraskan, meanwhile, complained about the ingratitude of football fans when only a small crew of volunteers showed up before the game to pick “small stones, sticks, and pieces of glass” from the field.[17] In November, the Lincoln High School football team refused to play a scheduled game at Nebraska Field after finding a sinkhole on the 10-yard line, apparently from an old well.[18]

It got better. The university improved the field and slowly added wooden bleachers until the space could hold no more. On November 30, 1922, some 16,000 fans packed Nebraska Field for a Husker victory over Notre Dame’s legendary “Four Horsemen” in the stadium’s final game.

Memorial Stadium groundbreaking, April 26, 1923. Chancellor Samuel Avery plowed a ceremonial furrow with a team of horses, just as Governor McKelvie had done a year earlier at the state capitol groundbreaking. The view here is west across 10th Street (today’s Stadium Drive), a little north of V(ine) Street. West Stadium stands here. RG2758-21-3

As in 1909, the construction of Memorial Stadium was something of a rush job. When the old wooden bleachers were torn down in early 1923, it was not clear that the new stadium would be finished in time for football season—or that fundraisers would bring in enough money to pay the contractors. They would have to do it without tax dollars.

Fundraising had begun in 1920 for a grand World War I memorial that was to include a museum, stadium, and gymnasium. But the farm economy fell on hard times in the early 1920s. The legislature not only refused to fund the project, but also cut the university’s operating budget. Meanwhile, opposition mounted across the state as local groups and American Legion chapters feared that fundraising for Lincoln would make it that much harder to build their own local war memorials.

The university scaled back its plans, dropping everything but the 30,000-seat football stadium. As head of the university’s alumni association, a man named Harold Holtz led an aggressive fundraising drive that used high-pressure tactics on students, faculty, alumni, and communities.

“On numerous occasions Holtz stated that none of the students had been coerced into pledging, but the peer pressure must have been tremendous,” writes Michelle Fagan in a 1998 issue of Nebraska History. She goes on to describe how Holtz and his team threatened and even sued people who did not fulfill their pledges.[19]

Was the stadium finished in time for the first home game of the 1923 season? Close enough. Contractors warned that they would not be held responsible for injuries when the university opened the partly finished stadium on October 13, 1923. No fans were hurt amid the scaffolding—and a few even climbed atop the unfinished upper balcony—but the Oklahoma Sooners did not fare so well. The Sooners became the first team to lose a game at Memorial Stadium, falling to the Huskers 24-0.

Memorial Stadium dedication, October 20, 1923. Nebraska played Kansas to a scoreless tie that day. A week earlier the Huskers defeated Oklahoma in the unfinished stadium’s first game. RG2758-21-9

Looking north at Memorial Stadium circa 1930. The empty field just south of the stadium is where Nebraska Field stood. Tenth Street runs along the left side of the photo; Richards Hall and Brace Laboratory are just to the right at the bottom of the photo, standing on the location of the original football field. RG2158-1-49

Notes:

[1] “Nebraska’s Two Athletic Fields,” Daily Nebraskan, Nov. 24, 1909.

[2] “Nebraska’s Two Athletic Fields.”

[3] Albert M. Troyer, “The University’s First Foot-Ball Team,” The Hesperian, Feb. 15, 1894: 30-32. The Hesperian was the university’s student newspaper, the predecessor of the Daily Nebraskan.

[4] Team booster Roscoe Pound recalled the overalls in a speech reported in the Lincoln Evening Call, Dec. 4, 1897.

[5] “A Complete Walk-Away,” The Hesperian, Nov. 1, 1891: 9.

[6] Based on various reports in The Hesperian.

[7] “Good Football Promised,” Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln), Oct. 15, 1897; “Senior Class Meeting,” The Hesperian, Nov. 21, 1899: 3.

[8] Daily Nebraskan, Feb. 20, 1904: 1.

[9] “May Change the Plans,” Daily Nebraskan, Feb. 24, 1901: 1; “Board Fixes It Up,” Daily Nebraskan, March 1, 1904: 1. Around this time, the Regents considered moving the university to the “farm campus,” as East Campus was then known.

[10] “Gridiron Will Remain on University Campus,” Lincoln Evening News, May 2, 1904: 1.

[11] “A New Athletic Field,” Daily Nebraskan, Nov. 24, 1904: 2; “Regents’ Report,” Daily Nebraskan, Jan. 19, 1905: 1.

[12] Nebraska’s Position in the Missouri Valley Conference,” Daily Nebraskan, Nov. 26, 1908: 1.

[13] “Must Be A Success,” Daily Nebraskan, Dec. 3, 1908: 1.

[14] “An Athletic Field,” Lincoln Star, Nov. 17, 1908: 6; “To Buy Land South of the University Campus,” Daily Nebraskan, Oct. 7, 1909: 3.

[15] “Act in Securing Lots,” Daily Nebraskan, April 21, 1909: 1; “Regents Held a Meeting,” Nebraska State Journal, April. 23, 1909: 8; “Athletic Field Is Now Assured,” Lincoln Star, June 15, 1909: 11; “Plans for Athletic Field,” Nebraska State Journal, June 27, 1909.

[16] “New Nebraska Field is Dedicated Today,” Daily Nebraskan, Oct. 23, 1909: 1; “Iowa and Nebraska Fight Furious Battle to a Tie,” Daily Nebraskan, Oct. 26, 1909: 1. The Huskers also played a home game at Omaha’s Vinton Street Park on October 16.

[17] “Stiff Practice at State Farm Grounds,” and “Only a Few Respond to Call for Workers,” Daily Nebraskan, Oct. 22, 1909: 1.

[18] “Athletic Field Shows Holes,” Daily Nebraskan, Nov. 17, 1909: 1.

[19] Michele Fagan, “‘Give ‘Till It Hurts’: Financing Memorial Stadium,” Nebraska History 79 (1998): 179-191 (Link goes to PDF.)