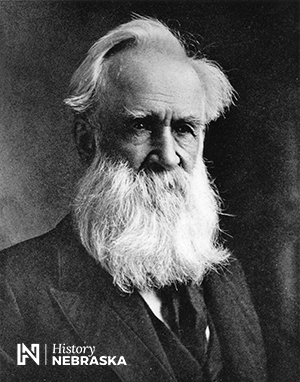

Benton Aldrich was man who got on other people’s nerves. He registered the deed to his Nemaha County farm in his wife’s name so she could vote in school elections. He advocated for Darwinian evolution and refused to join a church. He hired black farm workers and paid them the same as whites (though he still held racist views). He feuded with neighbors over control of the local cemetery, and was remembered by one of his own granddaughters as pompous, narrow-minded, and bigoted.

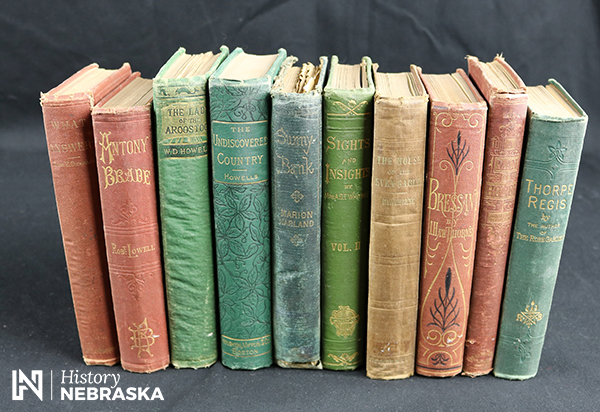

But what a collection of books he had.

Aldrich believed that his rural Nemaha County community needed a first-class library, so in 1876 he organized the Clifton Library Association, a subscription lending library that for years rivaled the best libraries in Nebraska in both quantity and quality of books and periodicals. (This was before publicly-funded lending libraries were common.)

Aldrich believed that his rural Nemaha County community needed a first-class library, so in 1876 he organized the Clifton Library Association, a subscription lending library that for years rivaled the best libraries in Nebraska in both quantity and quality of books and periodicals. (This was before publicly-funded lending libraries were common.)

The 1882 printed catalog lists 678 titles in fifteen categories, including both popular books and the most important works in science, agriculture, and other fields of study. “It could have been a college library at the time, and probably contained volumes the not-much-larger fledgling Nebraska academic libraries would have liked to have in their collections,” writes John Irwin in the Summer 2018 issue of Nebraska History.

Remarkably, this impressive library was housed not on a university campus, but in the dugout sod home of an unschooled but highly educated farm family. Aldrich didn’t own all the books (though he was an avid collector). Members could loan their personal books, and member dues paid for new books and magazines to be owned in common. At its peak, Clifton Library had four branch locations up to 22 miles away. “It was in effect a county-wide library system,” Irwin writes.

Aldrich may have been hard to get along with at times, but he was committed to rural culture and education. The Clifton Library is part of the same cultural trends that produced the Lyceum and Chautauqua movements, both of which were dedicated to bringing culture and learning to all ages across rural America. Irwin and many like-minded people were serious about living out Thomas Jefferson’s ideal of a nation of educated, independent farmers—even as the nation was becoming gradually more urban and industrialized.

For Aldrich, books and farming went together quite naturally. He was passionate about both, and was a pioneer in promoting “scientific farming” in the years before university-based agricultural extension programs.

Public libraries eventually replaced private subscription libraries. The Clifton Library books went back to their private owners, but some of them—including those pictured above—were later donated with Aldrich’s papers to History Nebraska.

Look for “A Farmer’s Passion for Knowledge: Benton Aldrich and the Clifton Library Association” in the Summer 2018 issue of Nebraska History.

History Nebraska members receive quarterly issues of Nebraska History as part of their membership; single issues are available for $7 from the Nebraska History Museum (402-471-3447).

—David L. Bristow, Editor