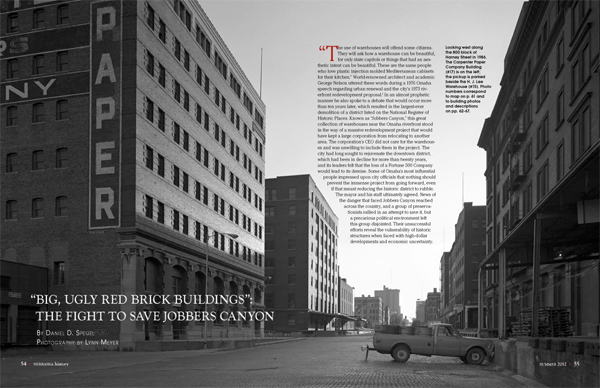

“The use of warehouses will offend some citizens. They will ask how a warehouse can be beautiful, for only state capitols or things that had an aesthetic intent can be beautiful. These are the same people who love plastic injection molded Mediterranean cabinets for their kitchen.” World-renowned architect and academic George Nelson uttered these words during a 1976 Omaha speech regarding urban renewal and the city’s 1973 riverfront redevelopment proposal. In an almost prophetic manner, he also spoke to a debate that would occur more than ten years later, which resulted in the largest-ever demolition of a district listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Known as “Jobbers Canyon,” this great collection of warehouses near the Omaha riverfront stood in the way of a massive redevelopment project that would have kept a large corporation from relocating to another area. The corporation’s CEO did not care for the warehouses and was unwilling to include them in the project. The city had long sought to rejuvenate the downtown district, which had been in decline for more than twenty years, and its leaders felt that the loss of a Fortune 500 Company would lead to its demise. Some of Omaha’s most influential people impressed upon city officials that nothing should prevent the immense project from going forward, even if that meant reducing the historic district to rubble. The mayor and his staff ultimately agreed. News of the danger that faced Jobbers Canyon reached across the country, and a group of preservationists rallied in an attempt to save it, but a precarious political environment left this group disjointed. Their unsuccessful efforts reveal the vulnerability of historic structures when faced with high-dollar developments and economic uncertainty.

“The use of warehouses will offend some citizens. They will ask how a warehouse can be beautiful, for only state capitols or things that had an aesthetic intent can be beautiful. These are the same people who love plastic injection molded Mediterranean cabinets for their kitchen.” World-renowned architect and academic George Nelson uttered these words during a 1976 Omaha speech regarding urban renewal and the city’s 1973 riverfront redevelopment proposal. In an almost prophetic manner, he also spoke to a debate that would occur more than ten years later, which resulted in the largest-ever demolition of a district listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Known as “Jobbers Canyon,” this great collection of warehouses near the Omaha riverfront stood in the way of a massive redevelopment project that would have kept a large corporation from relocating to another area. The corporation’s CEO did not care for the warehouses and was unwilling to include them in the project. The city had long sought to rejuvenate the downtown district, which had been in decline for more than twenty years, and its leaders felt that the loss of a Fortune 500 Company would lead to its demise. Some of Omaha’s most influential people impressed upon city officials that nothing should prevent the immense project from going forward, even if that meant reducing the historic district to rubble. The mayor and his staff ultimately agreed. News of the danger that faced Jobbers Canyon reached across the country, and a group of preservationists rallied in an attempt to save it, but a precarious political environment left this group disjointed. Their unsuccessful efforts reveal the vulnerability of historic structures when faced with high-dollar developments and economic uncertainty.

Jobbers Canyon’s historical significance is rooted in the settlement of the West, and to many mid-nineteenth century pioneers, the frontier began on the Missouri River’s western shore. In 1854 the Kansas-Nebraska Act opened the door, and many people crossed the river at Council Bluffs, Iowa, to settle in the new town of Omaha. Pioneers chose this location, in part, because it offered many opportunities for trading and transportation ventures.

Omaha grew outward from its birthplace on the banks of the Missouri River, but the center of commerce did not stray too far inland. Businesses such as transportation, manufacturing, and trading companies strategically anchored themselves near the natural shipping network afforded by the river, an area that became even more desirable after Omaha was selected as the eastern terminus of a new transcontinental railroad in 1863. Around 1880, with Omaha cemented as a major transportation hub to the western United States, a thriving wholesale jobbing industry established itself in the city. “Jobbers,” who purchased commodities directly from manufacturers and sold them to retail outlets, weathered the volatile economic conditions of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and helped propel Omaha’s commercial growth.

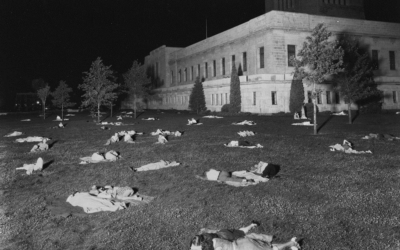

Utilizing the moniker “Omaha the Market Town,” the Omaha Jobbers and Manufacturers Association advertised heavily during the spring and fall buying seasons. One such advertisement described Omaha and its business climate as “the largest jobbing and manufacturing market in this territory. It is so located that the transportation problem and the freight problem are simplified for every merchant in the central west. The stocks carried here are as varied as any in the country and the methods of doing business are the most pleasant and agreeable.” Another declared, “Omaha jobbers have conformed to the requirements of retail trade in every way and not only do they guarantee their goods, but their prices and delivery-all are adjusted to meet the needs of merchants. Omaha is now recognized by progressive merchants of the central west as the most inviting and in every way the most satisfactory market in which to trade.” Around the turn of the century, some of the city’s largest wholesale companies built impressive warehouses, with a concentration just west of the river at a place of higher elevation less prone to seasonal flooding. Because the massive structures created an urban “canyon” along a three-block stretch of Ninth Street, the district was eventually known as “Jobbers Canyon.”

Conditions that framed the demise of Jobbers Canyon developed slowly for more than twenty years. Downtown Omaha remained the center of commerce well into the twentieth century, but its dominance waned as the city grew outwards. The 1960s and 1970s saw the construction of a highway system, industrial and office parks, and suburban shopping centers such as Crossroads Mall and Westroads Mall, which helped draw new housing developments farther from downtown. Omaha decentralized as its population density thinned with the far-flung developments-an experience it shared with many other U.S. cities. By the end of the 1970s, the downtown district lost its place as Omaha’s regional retail and office center. City leaders recognized the decline; as former Omaha City Planning Director Marty Shukert put it, they began a decades-long “search for a new downtown vision, a far-ranging and ambitious effort to re-invent a city center that was growing more distant from the geographic center of the changing city.”

The entire essay appears in the Summer 2012 issue