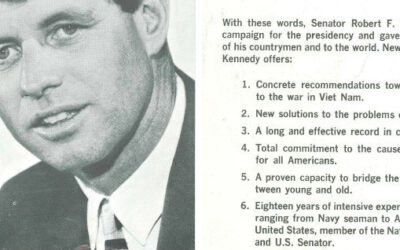

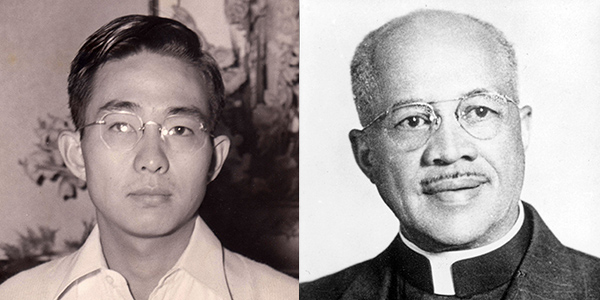

Above photos: left: Joseph Ishikawa (courtesy of Jesse Ishikawa); right: Rev. Trago T. McWillams (History Nebraska RG2411-3675)

Joseph Ishikawa came to Nebraska from a Colorado internment camp during World War II. As a city employee in 1946 he challenged a longstanding policy barring African Americans from the municipal pool. When a multiracial coalition pressured city leaders, officials claimed they didn’t support the rule… even as they resisted changing it.

Jesse Ishikawa, Joseph’s son, writes about the controversy in the Fall 2018 issue of Nebraska History Magazine. Jesse, a retired attorney living in Madison, Wisconsin, supplements public records and newspaper reports with his father’s notes and correspondence from the time. The result is a vivid portrait of how racial prejudice functioned in a northern city.

The son of Japanese immigrants, Joe Ishikawa was born in Los Angeles and grew up in the racially-mixed East Hollywood neighborhood. He graduated from UCLA in 1942. In post-Pearl Harbor America, Ishikawa and other West Coast Japanese-Americans faced incarceration due to prejudice and wartime paranoia. US citizenship did not protect them.

Ishikawa spent six months behind barbed wire in California and Colorado, but he was one of the lucky ones. He was able to shorten his internment by being accepted into graduate program at the University of Nebraska—one of the few universities at the time to accept even a limited number of students of Japanese ancestry.

Lincoln’s African American community, meanwhile, faced racial prejudice every day. Northern segregation wasn’t usually as blatant as its Southern counterpart, but it was real. When the Lincoln municipal swimming pool opened in 1921, Rev. Trago T. McWilliams brought his 12-year-old son to swim—and was turned away. He protested to Lincoln mayor Frank Zehrung to no avail.

Mayor Zehrung didn’t defend the policy. He blamed other people. Sure, it seemed unjust, he said, but “there were comparatively few colored people in Lincoln and . . . a much larger number of white people would feel that it was unjust to permit Negroes to use the pool.”

This is exactly the sort of reasoning that Joe Ishikawa encountered a quarter century later. After the war Ishikawa worked for the city’s recreation department. When he learned that black children were not admitted to the city pool, he resigned his position in protest.

Lincoln Municipal Pool, July 11, 1935. History Nebraska RG4290-1408

Bear in mind that the pool was not whites-only. African Americans were the only non-white group barred. Ishikawa was welcome to use the pool himself. But having been unjustly imprisoned because of racial prejudice, Ishikawa felt duty-bound to oppose prejudice wherever he found it, even if it wasn’t directed is his particular group.

“Please do not regard this as a hostile move on my part against any individual,” he wrote to his boss. “I do not think that any one person is any more responsible than any other citizen of the community for allowing such an injustice to exist, and I am taking this method as a citizen of this community to try to rectify my part of this wrong.”

Ishikawa began mailing letters to city officials and building a coalition to fight the rule—which had been allowed to stand for 25 years despite being illegal under Nebraska law. The city’s director of recreation, James Lewis, accused Ishikawa of stirring up trouble. Lewis claimed that he was not prejudiced himself, but he worried that if the rule was changed, “other people” might object.

“It’s always other people,” Ishikawa remembered thinking. “I haven’t seen an honestly prejudiced person yet.”

And that—and not open expressions of racism—was the main obstacle that segregation opponents faced. A multiracial coalition of local leaders began to pressure the city council. Prominent among them was Rev. Trago O. McWilliams, son of Trago T., and who as a 12-year-old had been turned away from the pool shortly after it opened.

The group was prepared to file a lawsuit, but tried political pressure first. Ishikawa’s comments about Lewis provide a clue to their strategy:

“Mr. Lewis is extremely political in the worst non-Aristotelian sense of the word. He is afraid of what he calls ‘trouble.’ At the same time, he regards me as a trouble maker. The implication is that if our side creates a greater degree of ‘trouble’ for their not opening the pool than can be caused by their opening the pool, he would switch his stand.”

“Trouble” came peacefully through publicity and well-attended city council meetings. The group embarrassed the city council into doing the right thing.

And the much-feared “other people” got over it.

— David L. Bristow, Editor

Read the entire article (PDF): “The Desegregation of the Lincoln Municipal Swimming Pool,” by Jesse S. Ishikawa, from the Fall 2018 issue of Nebraska History Magazine.

Household Plus History Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History Magazine annually.