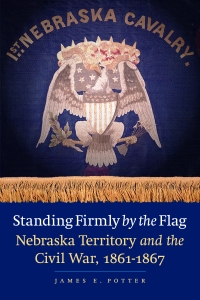

For the full story of Nebraska Territory during this dramatic era in American history, see James E. Potter, Standing Firmly by the Flag: Nebraska Territory and the Civil War, 1861-1867 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012).

For the full story of Nebraska Territory during this dramatic era in American history, see James E. Potter, Standing Firmly by the Flag: Nebraska Territory and the Civil War, 1861-1867 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012).

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the election of 1864, one of the most momentous in American history. Abraham Lincoln’s re-election as president on November 8, 1864, virtually assured that the Civil War would continue until Union victory was achieved and the institution of slavery was destroyed. Another hallmark of that year was Nebraska Territory’s failure to take advantage of an opportunity to become a state. In April Congress passed an enabling act authorizing Nebraskans to adopt a state constitution complying with certain conditions that, if met, would have led to immediate statehood. However, no constitution was drafted and Nebraska remained a U.S. territory whose residents could not vote in presidential elections until statehood finally came in 1867.

As for the 1864 election, Civil War historian James M. McPherson (Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction) has termed it unique in history because it was held in the midst of a civil war that would decide the nation’s future. Moreover, no other society had ever let its soldiers vote in an election whose outcome might determine whether they would have to keep on fighting. Both Lincoln’s supporters and critics knew that if Lincoln were returned to the White House and the Republicans maintained control of Congress, the war would go on to its bitter end.

The election presented Democrats in the North with a dilemma. A significant number, whose most prominent spokesman was former Ohio Congressman Clement L. Vallandigham, argued that the war was a failure and that the Union could be saved only by an immediate end to hostilities and a negotiated peace. They were known as “Peace” Democrats (also called “Copperheads”) and many Republicans considered them sympathetic to the Confederacy at best and traitors at worst. By contrast, the so-called “War” Democrats believed that the Southern armies must be defeated on the battlefield before peace could be restored, although they disagreed with many of Lincoln’s policies toward achieving that goal, such as the emancipation of slaves and the enlistment of black soldiers in the Union army.

As the time neared for holding party conventions, the Peace Democrats’ argument that Lincoln and his administration’s prosecution of the war had been a failure was bolstered by a seeming stalemate on the battlefields and by the tremendous number of Union army casualties sustained in bloody fighting during the spring and summer. In the absence of decisive Union victories over the Confederate armies, many Republicans and even Lincoln himself doubted his chances for re-election by a war-weary electorate.

When the Democrats met in convention in late August 1864, the Peace wing of the party wrote the platform, which declared the war a failure and called for the immediate cessation of hostilities and a peace convention among the states. However, the party nominated former Union general George B. McClellan, a War Democrat, for president. McClellan accepted the nomination, but only on the basis of the Confederacy first laying down its arms and agreeing to return to the Union. Only then would issues such as the fate of slavery be negotiated.

The Democrats’ divided approach to the critical question of how the rebellion should be ended did much to energize both citizens and Union soldiers in support of Lincoln’s re-election. As historian McPherson has noted, the “peace at any cost” platform allowed the Republicans to affix the Copperhead label to the entire Democratic Party. But what really tipped the balance in Lincoln and the Republicans’ favor were Union victories at Mobile Bay in late August, General Sherman’s capture of Atlanta in early September, and the defeat of Confederate forces in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley during September and October. These victories provided a powerful counterpoint to the Peace Democrats’ claim that the war was a failure.

The result was a Lincoln landslide of 212 electoral votes to McClellan’s 21, and a Republican gain of 37 seats in Congress. An estimated 78 percent of the vote cast by soldiers in the Union army went to Lincoln. As one Nebraska soldier wrote, “It would be strange indeed if, after more than three years of hard service to sustain the unity and integrity of the government, they had turned square about and said, ‘We are wrong, and this war is a failure.'” It was now clear that the fighting would continue until final Confederate defeat and with it would come the end of slavery in the United States.

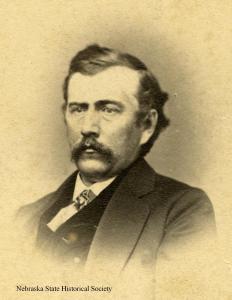

Although Nebraskans could not vote in the presidential election, her politicians and citizens were not immune from or unmindful of the issues at play in this critical national election. The balloting for Nebraska Territory’s nonvoting delegate to Congress, which was held on October 11, was also affected by the national debate about the war. War Democrat George L. Miller was his party’s nominee, while Phineas W. Hitchcock was the Republican Party’s candidate. Although the Nebraska Democratic platform endorsed McClellan’s “reunion first, peace second” approach and said nothing about Lincoln’s policies, the Nebraska Democrats could not avoid fallout from the “peace” plank in the national party platform. The territory’s Republican press had a field day castigating Miller and the national party as Copperheads who were trying to run on “Peace and War both.” The Nebraska Republicans strongly endorsed Lincoln’s re-election and urged that the rebellion be quelled “by force of arms.”

When the votes had been counted, Hitchcock had defeated Miller for the delegate’s seat in Congress by more than a thousand votes, signaling that the majority of Nebraskans did not think the war was a failure. In a letter to his friend J. Sterling Morton a few days later, Miller blamed the Peace wing of the national party for his own defeat and correctly predicted that the party’s peace platform would lead to Lincoln’s re-election:

Differing with, but always admiring the talents and intrepid courage of Vallandigham, I think at this hour that, if his cause has been fearless, it has been unfortunate for the Democracy everywhere. I refer to that part of his political career which has been distinguished by his efforts to engraft upon the policy of our party too much of his radical peace ideas. . . . [I]t does seem to me that his course in regard to the war, while it may have been conscientious on his part and grant, if you demand it, that in the abstract, if it can be so considered, it has been right; yet, with all this, it has certainly weakened the great party by running counter to the public judgment of the country and instead of moulding itself to the currents of popular opinion, it has fatally undertaken to resist them. Instead of accepting the expediency of yielding something to the passions of the dreadful crisis of civil war and conflict, it has vainly undertaken to struggle with them by forcing issues upon the Democracy which we all fear the result will prove to have been unwise and impolitic.

It took years for the Democrats (both in Nebraska and nationally) to overcome the perception that they were not only responsible for the Civil War (the party’s Southern wing had promoted secession in 1860-61) but that they had very nearly helped the Confederacy achieve its independence and the destruction of the Union by their course in the 1864 election. Nebraska, settled soon after statehood by thousands of Union veterans, elected Republicans to almost every statewide office until 1890. And aside from Andrew Johnson, a War Democrat elected vice-president with Lincoln in 1864 and who became president after the latter’s assassination, no Democrat reached the White House until Grover Cleveland was inaugurated in 1885.

For the full story of Nebraska Territory during this dramatic era in American history, see James E. Potter, Standing Firmly by the Flag: Nebraska Territory and the Civil War, 1861-1867 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012). Civil War buffs will also be interested in Marching with the First Nebraska: A Civil War Diary, edited by Potter and Edith Robbins, and published by the University of Oklahoma Press in 2007. – James E. Potter, Senior Research Historian / Publications.

(Updated in October 2023.)