“I guess there ain’t any end to Omaha,” wrote sixteen-year-old Frisby Rasp in a letter to his parents in 1888. “You can walk till you are tired out in any direction you choose, and the houses are as thick as ever….” Rasp’s letters show us how the city looked, sounded, and smelled to an 1880s farm boy.

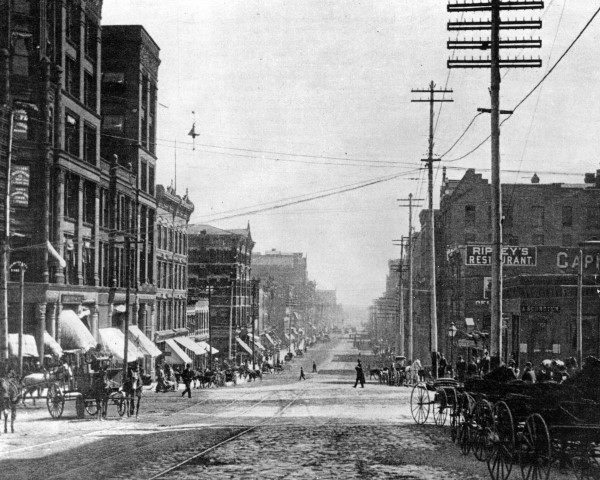

(Photo: Looking east along Farnam Street, Omaha, 1889. History Nebraska RG2341-28 )

By David L. Bristow, Editor

“I guess there ain’t any end to Omaha,” wrote sixteen-year-old Frisby Rasp in a letter to his parents in 1888. “You can walk till you are tired out in any direction you choose, and the houses are as thick as ever….”

Rasp grew up on his parents’ farm in southwest Polk County, Nebraska, the oldest of six children. Now he enrolled in the Omaha Business College at 16th and Capitol Streets. He paid $40 for tuition, and one of his teachers helped him find a boarding house. For the first time in his life, he was on his own in a big city.

“Big city” is relative. That year’s Omaha City Directory claimed a population of 125,000, a huge (and probably exaggerated) jump over the 30,000 counted in the 1880 census.

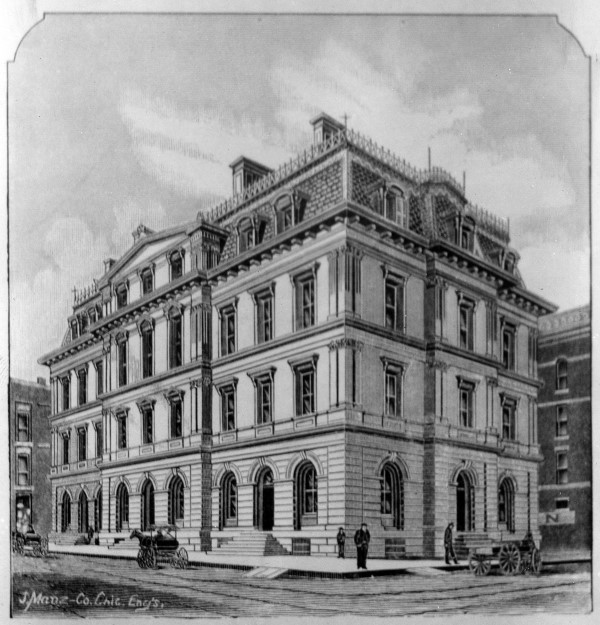

But it seemed big enough to Frisby. Even the post office on the northeast corner of 15th and Capitol was enormous, “a large three story stone [building]. It covers half a block. They receive over a carload of mail every day.”

(Omaha’s post office in 1888. History Nebraska RG2341-0-247)

He was writing on May 6, one day after he arrived. In his May 7 letter he reminded his family that “I haven’t got any letters yet,” but hoped there’d be one waiting for him at the big post office. He admitted he’d been “feeling pretty lonely.” Two days later he complained, “I haven’t heard from you yet; you must be dead. I ain’t a going to mail this until I do hear.” Two more long days passed before he received his long-awaited letters from home.

Rasp’s own letters over the next few months show us something that historic photographs don’t capture: how 1880s Omaha looked, sounded, and smelled to a rural Nebraskan of the time. Rasp’s portrait is vivid, though not always flattering.

“Every thing here is coal smoke and dirt and people,” he wrote soon after his arrival.

“It is dusty just as soon as it quits raining,” he added later, “and the dust here is the worst dust I ever saw. It is all stone and manure. Streets that ain’t paved, 2 feet deep of mud.”

Omaha was just beginning to pave its main streets. Rasp marveled at the “great steam roller” working in front of the college. But he soon tired of all the noise.

“I am getting so I hate to hear an engine,” he wrote on May 9. There must be at least 50 at work beside[s] the factories, and they never stop, night or day. It is puff-puff-puff-puff-toot-toot-toot-braw-braw-braw-puff-puff-puff-puff.”

He was overwhelmed by the crowds and anonymity. “I have seen more people since I came here than every person I ever saw before I came and with a few exceptions I never see the same person twice….” The nationwide bicycle craze was underway and Rasp saw so many that “I am sick a looking at them.”

Omaha was filthy by a country boy’s standards. On May 16 he promised to come home on a visit “and quit breathing smoke and drinking filth.” A few days later he added that “the water is full of sewerage. I haven’t drank a drop of water for a week. I don’t drink anything but coffee. The coffee hides the filth….”

The Rasp family was deeply religious, and Frisby was shocked by Omaha’s vice. “Every other store is a saloon,” he wrote before adding a quick reassurance: “but I never even looked in one….”

“This is an awful wicked town,” he noted several days later. “The saloons run on sunday [sic] and most all work goes right on.” A “bad house” operated next door to the college, and another brothel stood on the corner across from his boarding house. Even local newspapers, he wrote, claimed that if you shut down all the saloons, brothels, and tobacco shops, half of Omaha’s businesses would be gone.

Even so, when Rasp toured the county jail he seemed disappointed to report that “there was nobody in yesterday.”

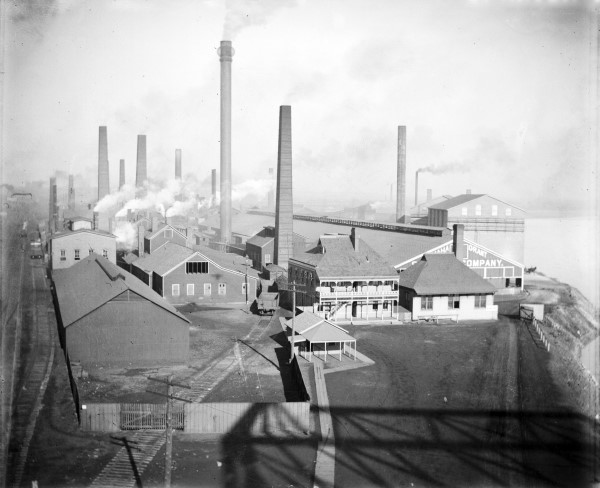

Rasp was an ardent tourist of local institutions. He marveled at the steam printing press at the Omaha Republican (“the fastest printing I ever saw”), witnessed “1000 carloads of lead and the biggest engine I ever saw” at the lead smelting plant, toured the city’s electrical power plant (another “largest engine I ever saw,” powering lights that are “40 times as good as gas”), and rode the elevator in a six-story hotel (“it is a beauty”).

(Omaha-Grant Smelting Co., December 29, 1902. History Nebraska RG3474-2038)

For all his complaining he seemed to be enjoying himself. He just didn’t want to stay.

“I wouldn’t live in the City always for anything,” he wrote. “Get an education there and a good start in life and then let me have a farm.”

Which is pretty much what he did. After graduation he worked as a bookkeeper in Omaha for two years, and later served as a business college instructor in York and a pastor in Wayland, but spent most of his life on a farm near Gresham. He and his wife, Mattie, raised seven children on the farm, and Rasp died there in 1948. His daughter Naomi Rasp Frederickson donated his letters to History Nebraska; edited and introduced by Sherrill Daniels, they were first published in Nebraska History Magazine in 1990.

This story first appeared in the May 2019 issue of NEBRASKAland Magazine.

Learn more about Frisby Rasp in the History Nebraska archives: RG4522.AM: Frisby Leonard Rasp Collection