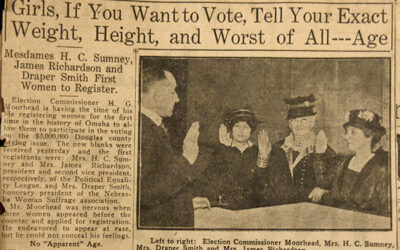

UNL professor and author Joseph Starita’s new biography, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche Overcame Racial and Gender Inequality to Become America’s First Indian Doctor came out in November of 2017. Susan La Flesche is also the subject of a new documentary entitled “Medicine Woman” for which Starita has served as an expert contributor. On March 14, 1889, Susan La Flesche received her medical degree―becoming the first Native American doctor in U.S. history. She earned her degree 31 years before women could vote and 35 years before Indians could become citizens in their own country. By age 26, this fragile but indomitable Indian woman became the doctor to her patriarchal tribe. She spent her life crashing through walls of ethnic, racial, and gender prejudice to improve the lot of her people. The History Nebraska collections feature prominently in both the book and the documentary. We caught up with Starita right before Thanksgiving to talk about researching and writing A Warrior of the People.

How long did the research process take you? I had the idea in 2010. It emerged as a result of Standing Bear research [Starita published Chief Standing Bear’s biography, I am a Man: Chief Standing Bear’s Journey for Justice, in 2010], which led me to the La Flesche family, which led me to Susan. I was very aware of the potential of a Susan biography from the arc of the research. So, beginning in January 2010, it was about five years of research. Not 52 weeks a year, but wherever I could grab a week. Much of it was during class holidays, and then exhaustive research in summer. By the end, I was pretty sure I had every scrap of paper in the world with the name “Susan La Flesche” on it.

What were some of your favorite primary sources? Susan spent so much of her early life on the East Coast away from her beloved Omaha people and beloved Omaha reservation. How she bridged the distance was a full-out assault on the U.S. postal system. She would write eight to ten letters a week sometimes. She divulged intimate details – what she was doing, people she was meeting, her innermost thoughts. She wrote about her fear, her exaltation, wanting to go home as soon as she could, how much she enjoyed autopsies. And in many Native cultures, it was forbidden to open up a dead body. It went against ancient native customs of never defacing the dead. The letters would contrast her seeing a Philadelphia concerto or the ecstasy of performing an autopsy against sheer loneliness of being away from her family. When you’re reading the innermost thoughts of the person you’re writing about, it’s one of those 10 shot Roman candle moments.

How was writing this book different than writing I Am a Man? The Standing Bear book told the story externally from the outside in. He didn’t write any letters. I compiled an enormous store of primary source documents to recreate what Standing Bear’s world was like, but that only allowed readers to go so far. In that book, it’s like the reader is watching Standing Bear go by on the highway, but in this book the reader is riding shotgun with Susan. There are incredibly intimate and human details. The research allowed me to tell her story from a female point of view. And why I think that’s important is because the American West over many decades has evolved into a mythical landscape. In dime store novels, photographs, Hollywood movies, television shows, the view has been framed from a male perspective. Readers of this book can walk up to the window into the past and see the window framed from a female viewpoint. And not just any female viewpoint, a knock-down-all-barriers female viewpoint.

Where did the majority of your primary resources come from? Four primary research tributaries flowed into the narrative river of Susan’s story. The most important was the Nebraska State Historical Society. Their La Flesche papers collection was an absolute goldmine with extensive primary documents. This family was very educated, fluent English speakers, and prolific letter writers. They wrote letters, diaries, and journals. The second tributary was the Hampton University archives and their primary source documents. The third was the Connecticut State Public Library. Their documents and letters on file showed me East Coast Susan. And the fourth tributary was the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. That institution and its records have been absorbed by Drexel University. The other important primary source was interviews with the Omaha people. All the books I’ve written that are cut from this cloth, I’ve tried to create a marriage between primary documents and the living, breathing people who know the history through oral tradition.

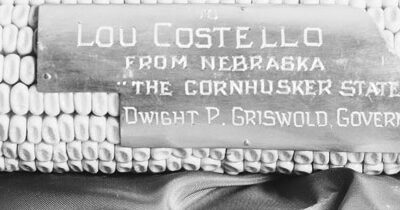

Indoor studio portrait of Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte after she returned to the Omaha Reservation,circa 1905. RGRG2026.PH0-000071

Indoor studio portrait of Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte after she returned to the Omaha Reservation,circa 1905. RGRG2026.PH0-000071

How did you decided how to cite your text? Why did you decide to forgo footnotes even though this is a historical text and many authors use them? Footnotes were never remotely a consideration. They’re visual roadblocks and speedbumps I don’t want to put the reader through. I want to tell a story without footnotes cutting across the grain. I put that information in the back of the book because that’s a better home for it. That said, it is extremely important in these kinds of books that you document where the information comes from to earn the trust of the readers. Still, I want readers in their chair turning the page, not looking for a footnote citation. The story has a certain momentum, a certain flow, and you want to pay attention to it. Your primary job as a writer is to get out of the way of the story. Do not let the story get filtered by your own biases or own perceptions or your own judgements. Purging footnotes from the story and parking them in a nice, neat warehouse in the back allows the story to come to the reader more directly and more powerfully.

What were some of your most powerful research moments? For a relatively brief period, Susan kept a day-by-day diary. That diary was just exquisite in its details. In many ways, the whole story builds toward “Chapter 9: A Warrior of the People,” which has the diary entries. I don’t have to tell readers how busy she was. I show them. I’m giving the reader the dots, but I’m giving the reader the breathing space to connect the dots. It is almost exhausting to read the diary entries, let alone live them. One hour she was helping a woman give birth, one hour she’s interpreting a legal document, the next hour she’s entertaining guests from the legislature, and the next she sees a sick child. If I had tried to tell the reader these things, I would have lost the emotional staying power of what it means to be a warrior of the people. Another research moment was when I had to track down a thirty-year-old article from the Sioux City Journal. The article reported for the first time that Walter Diddock, Susan’s brother-in-law, wrote a letter to Marie Curie about Susan’s cancer, and Marie Curie sent her a radium pellet. You can’t make that up. A two-time Noble Prize winning female doctor is sending a radium pellet to another female doctor in the middle of the Omaha reservation? It was so outlandish. I had to confirm the source. I knew this would be one of the certain moments in the book when readers would see a blinking yellow light and slow down and say, “Wait, is that really true?” But the Sioux City Journal reporter got the story firsthand from the son of Susan’s niece, which was the niece who attended her night and day. Those are the nitty gritty details. A second “blinking yellow light” moment was the issue of qualifying Susan as the first Indian doctor. I’ve seen the graduation certificates. There is absolutely no doubt that Susan was the first. Male or female. A lot of research firepower went into taking the wind out of the sails of people who would argue with that. Tracking down the Sioux City Journal reporter and digging in the weeds of medical records paid off.

How do you balance writing, researching, and teaching? If you have to have a full time job and you want to write, teaching is as good as you can do. You have the breaks to do research. You max out those breaks and amp up the research engine if you’re motivated enough. You can make a lot of research hay in four months.

How do you translate what you know from writing and researching to your students? By pounding into their heads that there’s always another question to ask, always another person to interview, always another document to fetch until you hit the bottom. If you have the energy and passion to keep drilling down, often a little nugget or jewel on a page is a result of that deep dive. All good writing begins with good reporting.

Outdoor photograph of Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte with her mother, Mary Gale LaFlesche, and two sons, Caryl and Pierre. This was taken at Dr. Picotte’s home in Bancroft. RGRG2026.PH0-000039

NET’s documentary Medicine Woman premiered in November. Watch it here: http://video.netnebraska.org/video/2365876471/