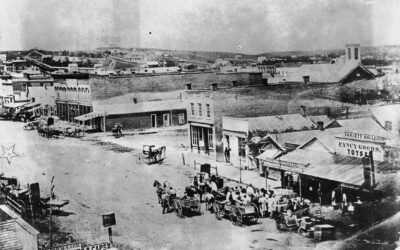

This is a story of a piece of office infrastructure that quietly helped create the modern world. Nebraska newspapers first carried ads for filing cabinets in the 1880s.

By David L. Bristow, Editor

“I can’t wait to read this blog post about early filing cabinets in Nebraska.” That may not be something you ever expected to say, but you’re saying it now, right? (And we have pictures! And ads!) This is a story of a piece of office infrastructure that quietly helped create the modern world.

In a May 2021 article in Places Journal, media historian Craig Robertson of Northeastern University writes that “because the modern world depends upon and is indeed defined by information, the filing cabinet must be recognized as critical to the expansion of modernity… Could capitalism, surveillance, and governance have developed in the 20th century without filing cabinets? Of course, but only if there had been another way to store and circulate paper efficiently.” Robertson’s article is adapted from his book The Filing Cabinet: A Vertical History of Information (University of Minnesota Press, 2021).

A whole book on filing cabinets? Robertson says he stumbled upon the subject when researching the history of the US passport. He learned that that for many years the US State Department kept diplomatic correspondence in chronologically bound volumes with limited indexing. In 1905, incoming Secretary of State Elihu Root became frustrated with the difficulty of retrieving departmental records. A former corporate lawyer, Root described his work at the State Department as that of “a man trying to conduct the business of a large metropolitan law-firm in the office of a village squire.” Root ordered the department to adopt a new information technology from the world of private business: a “numerical subject-based filing system housed in filing cabinets.”

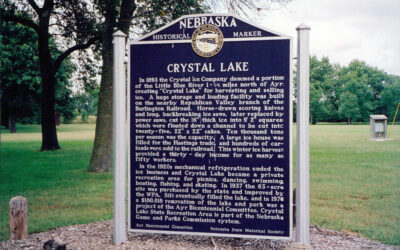

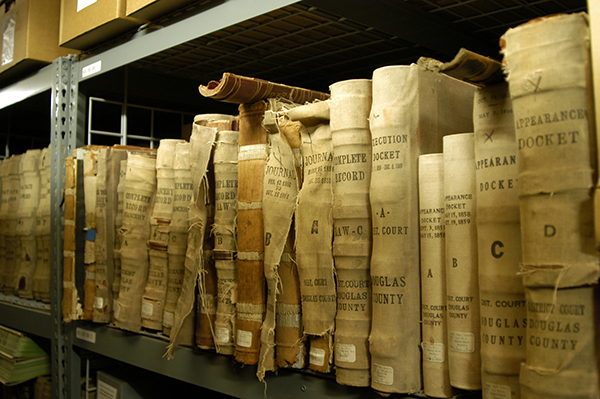

Photo: Nebraska Territorial Supreme Court records at History Nebraska. Before filing cabinets, public records were kept in bound volumes.

An invention of the 1890s, the vertical filing cabinet “quickly became a fixture throughout North America and around the world. It spread globally because it provided a way to store large amounts of paper so that individual sheets could be retrieved easily,” Robertson writes.

Today we’re familiar with “big data” and take for granted that businesses and governments store and can quickly retrieve huge amounts of information. On a smaller but still impressive scale, people expect to quickly locate items from History Nebraska’s extensive collections of objects and photos. Today we do this through an online database, but the concept dates to the filing systems developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The concept of information as discrete from knowledge—“information as a thing that could be standardized, atomized, and stripped of context”—in Robertson’s words, was a revolution in thought.

Let’s look at a few examples of how this revolution played out in Nebraska.

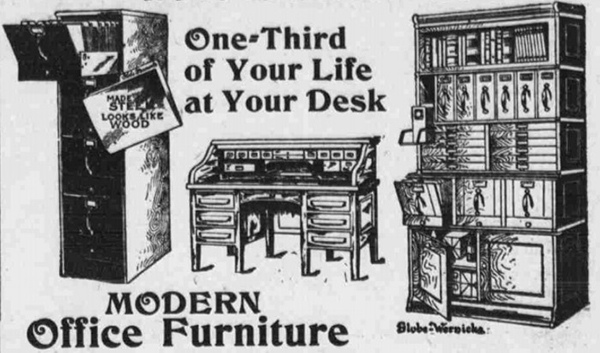

Nebraska newspapers first carried ads for filing cabinets in the 1880s. Early “letter filing cabinets” had a variety of configurations, as shown in these early 1900s ads.

The Commoner (Lincoln), May 29, 1903:

Omaha Daily Bee, Feb. 7, 1909:

Omaha Daily Bee, April 10, 1909:

Omaha Daily Bee, Jan 5, 1910:

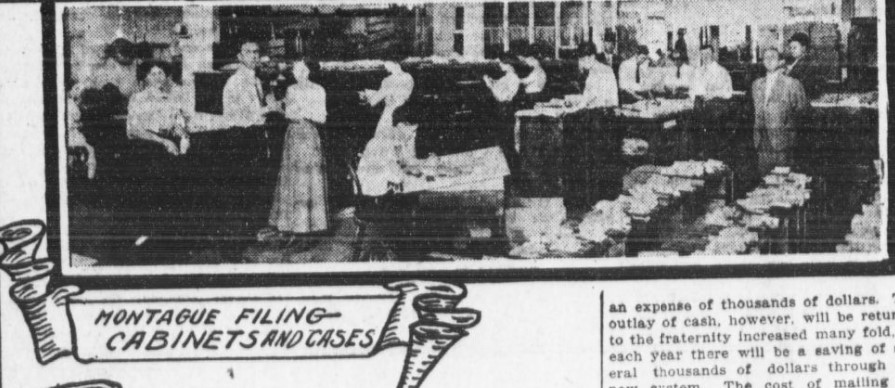

A glowing article about Woodmen of World (“Where Big Men With Big Ideas Do the Big Things” per the Bee, Sept. 11, 1911) shows how an insurance company used a modern filing system to produce mass mailings.

“First, the name of the member is embossed upon a double-seamed metal plate, which is used in all mailing and addressing machines… it is filed away in one of the steel cabinets. It, along with thousands of others, is removed from the filing cabinets whenever the official publication is ready for mailing.

“The address plates are fed to the publication addressor from the filing cabinets and are automatically refiled in them in the same order, without stoppage of the machine or the interruption of the work…

“The Woodmen have twenty-six truck cabinets, which are made of quartered oak and mounted upon rubber casters… Each cabinet has a capacity of 25,536 address plates.”

Modern filing systems allowed companies and institutions to operate efficiently at ever-larger scales, and the address plate system used by Woodmen was one of the new technologies making it cheaper than ever to publish subscription periodicals. This period of history saw an explosion of newspapers, magazines, mail-order catalogs, and direct marketing.

(Omaha Bee, Sept. 11, 1911)

By the mid-twentieth century, filing cabinets had long been a fixture of office life. Here is a circa-1940 Nathaniel Dewell photo of the showroom of Remington Rand Incorporated, 1319 Farnam Street, Omaha, showing the latest in modern office equipment.

(History Nebraska RG3882-32B-173)

In promotional photographs, filing cabinets often serve as a visual emblem of modernity and efficiency, as in this 1936 photo taken by Nathaniel Dewell at the Douglas County Courthouse in Omaha.

But did it really take two men to file a folder?

(History Nebraska RGRG3882-19-4-1)

In fact, most filing was done by women, as in this 1947 MacDonald Studio photo taken at Andrews Advertising in Lincoln. By the late nineteenth century, clerical work was increasingly performed by female employees.

“From its early arrival in offices,” Robertson writes, “the filing cabinet reflected and reinforced the gendered division between manual work and mental work, or women’s work and men’s work. In the 20th-century office, female file clerks were expected to handle papers, but not to understand their contents; in contrast, it was male managers and executives who read the files, performing jobs that purportedly required thought.”

(History Nebraska RG2183-1947-708-10)

Today more and more of our information is stored and used digitally. But the filing cabinet still guides us. When I wrote this blog post, I used no paper and opened none of the six metal filing cabinets in my office. I did my research online and uploaded the result to our web server—but I organized everything using a digital metaphor of an old, familiar technology from the nineteenth century, so common that we take it for granted:

(Posted Feb. 24, 2022)