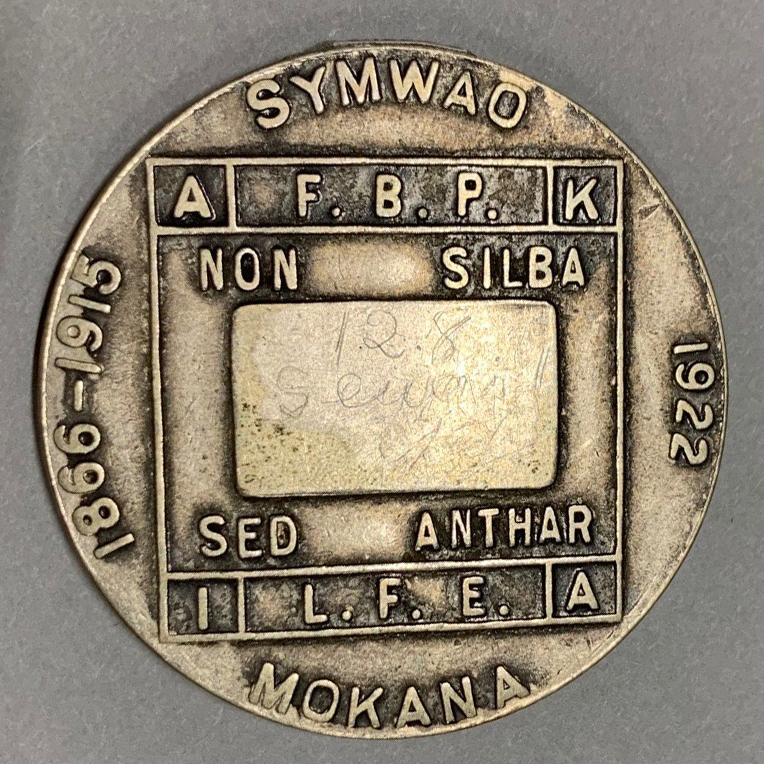

This pocket piece in History Nebraska’s collection served as a kind of membership card for admittance to Klan meetings. .It demonstrates how the KKK used symbolism and secret codes to promote its agenda.

By David L. Bristow, Editor

In the 1920s the Ku Klux Klan and its message of prejudice was mainstream, powerful, and even respected across the United States. At one point the Klan claimed to have 45,000 Nebraska members—probably an exaggeration, but it was big enough to dominate state governments in Indiana and Colorado, and was a force to be reckoned with elsewhere.

Though inspired by the original KKK of the post-Civil War South, the “second” Ku Klux Klan was a privately held corporation that was part hate group and part multi-level marketing scheme selling memberships, robes, literature, and tokens like this one to an eager membership.

This pocket piece in History Nebraska’s collection served as a kind of membership card for admittance to Klan meetings, or as something to show when meeting another Klansman. It demonstrates how the KKK used symbolism and secret codes to promote its message of white supremacy, nativism, and its militant brand of Protestantism.

The medallion invokes widely beloved symbols—the Constitution (with a cross superimposed), the Bible, and the US flag—essentially claiming them for the Klan under the slogan “ONE COUNTRY, ONE FLAG, ONE LANGUAGE.” Less prominent, to the left of the Constitution is a fasces, a bundle of rods associated with ancient Rome and symbolizing collective power and governance.

The unintentional irony is thick:

The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution promises equal protection under the law regardless of race or national origin; the Klan’s very existence was based on its members’ rejection of this idea.

Three-fourths of the Christian Bible is comprised of the Hebrew Scriptures, and the rest celebrates a certain Jewish rabbi; the Klan was anti-Semitic.

The Stars and Stripes had been the enemy flag in the eyes of the original 1860s Klansmen; the twentieth century Klan revered these Confederate terrorists as their spiritual predecessors.

None of these contradictions mattered to the Klan’s leadership. Klan ideology never emphasized intellectual coherence. Instead, it tapped people’s fears about where their country was headed. In the early twentieth century the United States was becoming increasingly urban and ethnically diverse. The Great Migration brought large numbers of African Americans to northern cities.

The Klan stoked existing fears that the country was becoming decadent and foreign. At the same time, the Klan invoked deeply held feelings of patriotism and religious reverence. It used all these emotions to fuel support for its social and political agenda.

The Klan was not secretive about its agenda, and it was so powerful and widely respected that members did not need to hide their identities. Still, like many other fraternal organizations, the Klan fostered feelings of specialness and belonging through the use of secret codes.

On the front side of the medallion, O.S.F.K. stands for “One School, Flag, Kountry.” (The Klan opposed Catholic schools and held that Catholicism was un-American. “Kountry” is an example of the Klan’s style of frequently spelling “c” words with a “k”.)

The reverse side is full of secret messages:

- SYMWAO: Spend Your Money With Americans Only.

- 1866 – 1915: The founding years of the first and second Ku Klux Klan

- A.K.I.A.: A Klansman I Am.

- Non Silba Sed Anthar: Not for self, for others

I haven’t learned what “F.B.P.,” “L.F.E.,” or “MOKANA” mean.

The donor of this particular token believes it belonged to his great-great grandfather, who lived in Waco, in York County, Nebraska. The words scratched on the reverse side are difficult to make out, but we believe they say “128 Seward” or “12 8 Seward.” (Waco is near Seward County.) Similar tokens were once carried in the pockets of many Nebraskans; numerous designs from this period are found nationwide.

(Posted March 28, 2022)

Read more about the KKK in Nebraska.

Read about the American Protective Association, a similar group in the 1890s.

Sources:

Linda Gordon, The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition (New York: Liveright, 2017).

Michael Schuyler, “The Ku Klux Klan in Nebraska, 1920-1930” Nebraska History 66 (1985): 234-256.

“Token – Ku Klux Klan,” Numista, https://en.numista.com/catalogue/pieces128517.html