In the racially segregated military that followed the Civil War, one of the first Cavalry regiments for black soldiers was headquartered in Nebraska for more than a decade. These soldiers played a notable role in social and military changes of the late 1800s. Brian Shellum tells the story of the Ninth Cavalry Regiment, which fought discrimination as well as Native Americans on the Great Plains.

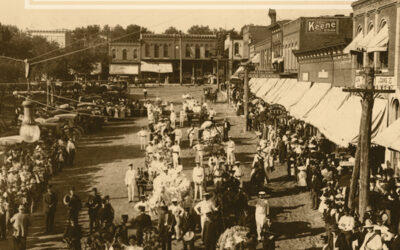

A Ninth Cavalry squadron on the drill field, circa 1892-93. Each of the four troops has its own guidon and its own color of horse.

The shadow of the reviewing stand is visible in the foreground; Crow Butte and a few of the Fort Robinson buildings are visible in the right background. RG1517-93-20

By the end of the Civil War, black volunteers made up about 10 percent of the Union’s manpower, had fought all over the country and had suffered 36,837 deaths. But it wasn’t until after the war that Congress established the first regular regiments of black soldiers – nicknamed “Buffalo Soldiers” by the Native Americans because of the soldiers’ dark skin and curly black hair. One of these regiments, the Ninth Cavalry, fought in the Apache Wars in New Mexico from 1875-1881, and was later headquartered at Fort Robinson, Nebraska from 1887 to 1898.

In terms of organization and equipment, the Buffalo Soldier Regiments were almost identical to white regiments in the Regular Army. Shellum explains that “the army simply could not afford to cripple one tenth of its combat power by deliberately issuing substandard items to the black regiments. The army bureaucracy was by regulation color-blind when it came to all things official such as recruiting, medical services, military pay, and pensions.”

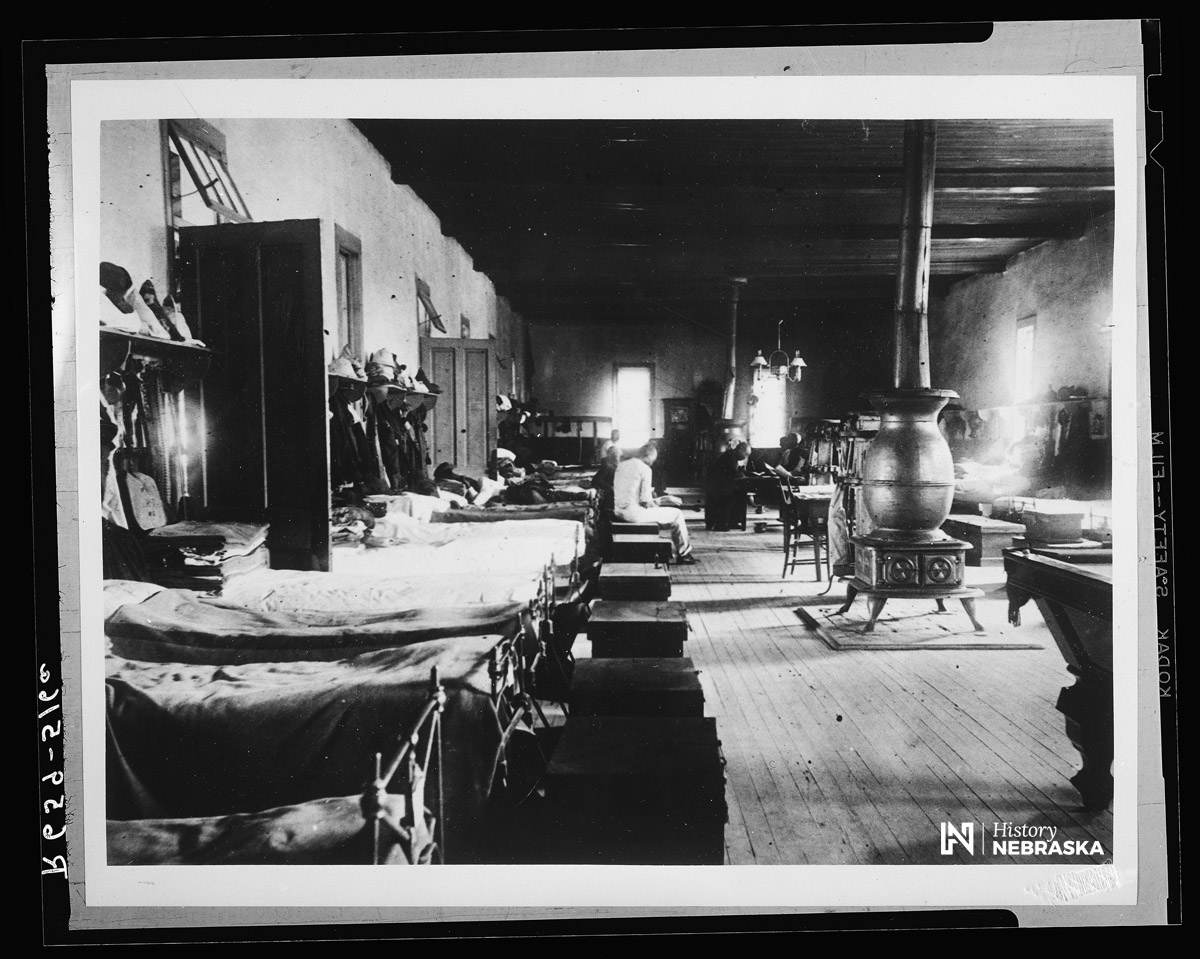

Interior of an 1887 adobe barracks at Fort Robinson.

The all-black Ninth Cavalry lived in buildings that were identical to those of their counterparts in the all-white Eighth Infantry. RG1517-93-13

However, that did not protect the Buffalo Soldiers from the fierce racism of some white regiments and officers. Fort Robinson hosted large numbers of black cavalry along with white infantry soldiers, creating what Shellum calls “a breeding ground for racism.” When Frank B. Taylor became an officer in the Ninth Cavalry, he made clear his contempt for the black soldiers and officers. In 1881 Taylor was court-martialed for verbally abusing, pistol-whipping, and beating a black trooper with the butt of a carbine. When the black Lt. Charles Young arrived at Fort Robinson in 1889, Taylor actively avoided serving with him.

Fortunately, not all the white officers were so hostile. Louis H. Rucker treated the enlisted men of the Ninth Cavalry with respect, and was a mentor to black officers John Alexander and Charles Young. Over time, the Buffalo Soldiers won the respect of others as well. Black regulars had higher enlistment rates but lower desertion rates than whites, causing Secretary of War Redfield Proctor to suggest raising a black artillery regiment.

The Buffalo Soldiers’ faithful service not only helped diffuse racial tensions, but also paved the way for future generations of black soldiers.