The medicine bundle of Oglala Lakota leader Crazy Horse is six feet deep somewhere in Minatare, Nebraska. A medicine bundle was a package that contained a man’s most sacred things – perhaps special stones, herbs, beads, or hair. The bundles were believed to have special power, and were guarded carefully by their owners. In the Spring 2014 issue of Nebraska History, Pulitzer Prize winner Thomas Powers tells the story of how Crazy Horse’s bundle was entrusted from one person to another for 65 years until it was buried for safekeeping in Minatare during World War II. Shortly before his death, Crazy Horse entrusted his medicine bundle to his close friend Fast Thunder, who took it to the new Pine Ridge Reservation after Crazy Horse was killed in 1877. When Fast Thunder died in 1914, his wife Jennie Wounded Horse preserved the bundle, then before she died entrusted it to Nellie Ghost Dog. Nellie Ghost Dog later passed it on to Theodore Means, the grandson of Fast Thunder.

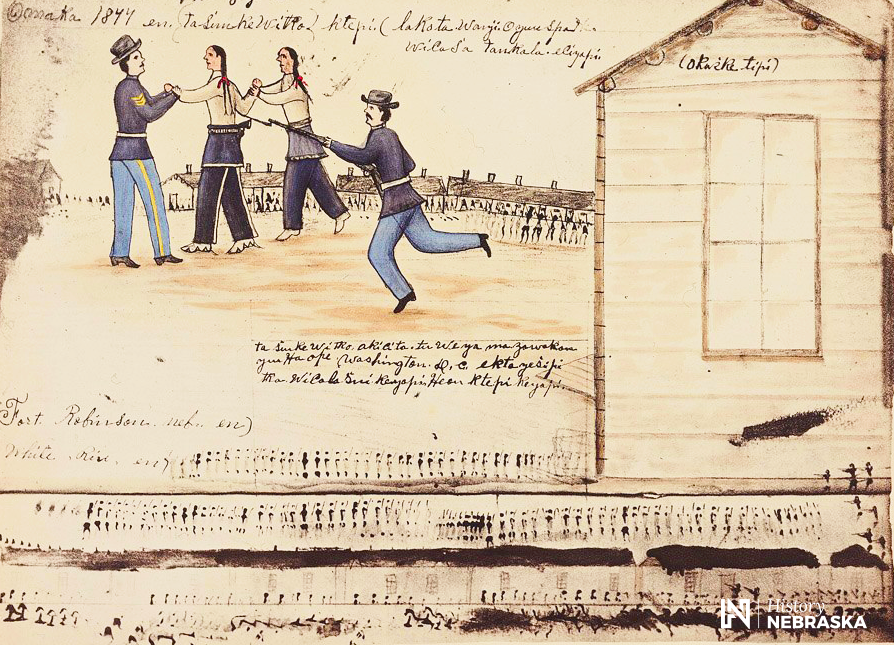

The death of Crazy Horse as portrayed by Amos Bad Heart Bull (ca. 1868-1913), an Oglala Lakota tribal historian known for his ledger art, which adapted traditional Native American pictography to the medium of paper. NSHS 11055-2241-18

In the 1930s, times were hard for the Oglala Lakota and jobs on the reservation were scarce. Theodore Means and others found seasonal work in Minatare picking potatoes, and hundreds of Indians would travel down from Pine Ridge every year to work in the fields. But the arrival of World War II made everything uncertain. The fall of 1942 was the last year in Minatare for a long time for Theodore Means – it was also the year he decided to bury Crazy Horse’s bundle, to keep it safe. The next year, Means joined the army and went to war. It was many years before anyone returned for the bundle. During that time, the war and the years after had completely changed Minatare. Many of the massive cottonwood trees were cut down, and the growing popularity of cars forced roads to expand and change. Means died in the early 1960s, and when his wife Theresa went to look for the bundle in 1968 or ’69, Minatare was unrecognizable. The landmarks had all changed, and the bundle was impossible to locate. Powers heard the story from Theodore Means’ granddaughter Barbara Adams, though it seemed that not everyone was comfortable with a white man hearing the story of Crazy Horse’s most guarded possession. In the article, Powers describes the day he went to Adams’ house to hear the details of the story.

While we talked Barbara’s mother was sitting at the kitchen table, playing solitaire. A young man was working out in the yard, building a chicken house. We could hear the hammering as he pounded in nails. The man and Barbara’s mother, whose last name was now Black Weasel, were thin as drinking straws. There wasn’t an extra ounce on either of them, probably not even as many ounces as they needed. Through the open doorway Margaret Black Weasel examined me closely. She was eighty years old and was smoking long cigarettes that hung from her lips as she sorted and slapped the cards. She looked straight down at the cards on the kitchen table in front of her with the smoke curling slowly up around her eyes and she listened as ferociously as I did…During my conversation with Barbara in the living room Margaret Black Weasel smoldered but did not protest or interrupt and bit by bit Barbara deepened the story she had told me the first time I met her.

While the bundle was no longer passed on, it may be that Crazy Horse wanted the contents of his bundle to remain a mystery. To Powers, the story of the lost bundle “marks a divide between the things that are lost and the things that survive.” – Joy Carey, Editorial Assistant, Publications