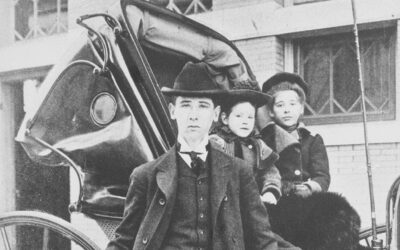

A 1924 event in Wilber, Nebraska, featured “Dan Desdune’s Band and Minstrel Show of Omaha. Colored Entertainers Supreme.” NSHS RG813-445.

Jazz critic and historian George Lipsitz has observed that “established histories of jazz tend to focus on a select group of individual geniuses in only a few cities.” This group includes figures such as Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Charlie Parker; and those few cities are New Orleans, Kansas City, Chicago, and New York. Lipsitz contends that many artists and cities that have been neglected in general surveys of jazz history merit attention and that Omaha, Nebraska, is one such place. Before the end of the dance band era, around 1960, many black musicians came to Omaha in order to develop their talents and try to work their way into big name bands.

Omaha jazz musician Preston Love asserted, “If New York, Chicago, and Kansas City were the major leagues of jazz, Omaha was the triple-A. If you wanted to make the big leagues, you came and played in Omaha.” Omaha’s black bandleaders had long upheld a tradition of nurturing and producing prominent musicians, many of whom had been attracted to Omaha from other parts of the country. Dan Desdunes was largely responsible for beginning this tradition.

The word “jazz” first appeared in The Monitor, Omaha’s black weekly newspaper, on November 3, 1917, less than a year after the first jazz recordings were made. This word was used in an advertisement for a charity ball at which the music was to be provided by the Desdunes Jazz Orchestra. This band was led by Dan Desdunes, who was described as the “father of negro musicians of Omaha” in Harrison J. Pinkett’s 1937 manuscript, “An Historical Sketch of the Omaha Negro.”

Desdunes was born in New Orleans in 1873 to an upper-middle class Creole family with a penchant for public service and notoriety. His grandfather, Jeremiah Desdunes, came from Haiti and his grandmother, Henrietta, was originally from Cuba. Dan’s father, Rodolphe Lucien Desdunes, was born in New Orleans in 1849. Rodolphe was a writer who, in 1911, published Nos Hommes et Notre Histoire, a book about the history and the culture of Creoles in Louisiana. Therein, Rodolphe highlighted the achievements of several successful Creoles. This work has been translated and reprinted many times, most recently in 2009.

Rodolphe was a staunch opponent of segregation and was one of the principal orchestrators of the Comité des Citoyens (Citizens’ Committee) on September 5, 1891. He was the primary editorial contributor to The Crusader, New Orleans’ weekly black newspaper, and held the meetings of the Comité des Citoyens at the newspaper’s offices. Rodolphe succinctly defined the objectives of the organization:

It was in 1890 that the Citizens’ Committee was formed, when a return to exaggerated fanaticism about caste or segregation once again alarmed the black people. This fanaticism was not confined merely to chance meetings. We were face to face with a government determined to develop and establish a system by which a portion of the people would have to submit to the rest. It was necessary to resist this state of affairs, even with no hope of success in sight. The idea was to give a dignified appearance to the resistance, which had to be implemented by lengthy judicial procedures.

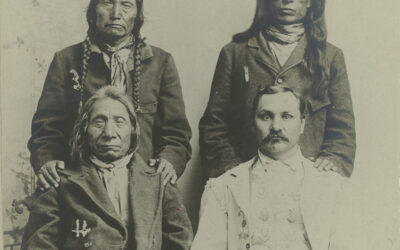

In 1890, the Louisiana Legislature enacted the Separate Car Act, which required railway companies to provide separate passenger cars for whites and blacks. It also required the railroads to physically halt anyone who attempted to enter a car reserved for persons of another race. After the Comité des Citoyens decided to challenge this law’s enforcement in interstate travel, Dan Desdunes volunteered, in February 1892, to violate this act. Desdunes was one-eighth black, and according to Louisiana law, legally classified as colored, which meant he was forbidden to ride in any white railroad passenger car. Desdunes’ skin color was light enough that he was able to pass as white and gain admission to a white only coach. The Comité des Citoyens was so certain that Desdunes would pass for white that it hired private detectives to arrest him in order to ensure that the committee could challenge the Separate Car Act in court. Dan Desdunes spent no time in jail because he was immediately bailed out by the committee. After a short trial, he was acquitted. Justice John Howard Ferguson ruled that enforcement of the Separate Car Act upon interstate travel was unconstitutional because only the federal government had the authority to regulate interstate commerce.

Next, the Comité des Citoyens decided to challenge racial segregation on intrastate railway travel. They recruited Rodolphe Lucien Desdunes’ friend, Homer Plessy, to be arrested in this challenge. This case eventually went to the United States Supreme Court, which ruled on May 18, 1896, that Homer Plessy’s constitutional rights had not been violated by Louisiana law. This ruling was devastating to Rodolphe, who reported that “our defeat sanctioned the odious principle of the segregation of the races.” Whereas Rodolphe primarily dedicated his life to scholarship and civil activism, Dan Desdunes pursued a livelihood in arts and entertainment. The son’s means may have differed from his father’s, but Dan’s career allowed him to work toward Rodolphe’s goals. Dan Desdunes not only became a musician and an educator, he also worked against racial segregation.

To read more about Dan Desdunes, check out Jesse J. Otto’s full article from the Fall 2011 issue of Nebraska History Magazine.