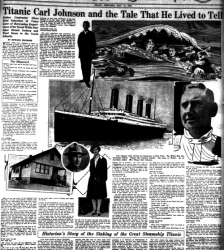

Ice gorge, Missouri River Flood, Niobrara. Date unknown. RG2118-5-16

Ice gorge, Missouri River Flood, Niobrara. Date unknown. RG2118-5-16

Last week’s Wild Weather Wednesday was so popular we decided to give you more of the story of Niobrara. The late John Carter wrote this piece for the Fall 1991 issue of Nebraska History. Nebraska is a state noted for colossal natural disasters. Prairie and timber fires blacken thousands of acres. Tornadoes level whole communities in minutes. Blizzards, notably the ones in 1888 and 1949, bring the entire state to a standstill. Nebraskans respond to these adversities with stoicism. They clean up, dig out, and rebuild. In 1881 the town of Niobrara, Nebraska, faced such a trauma – a flood – which deluged the town under three to six feet of water for more than a week. What was the response of the citizens of Niobrara? They picked up the town and moved it a mile and a half uphill! Niobrara was established in the spring of 1857 along the Missouri River about a mile southeast of its confluence with the Niobrara River. The town had been situated to provide easy access to steamboat traffic, and on June 29, 1857, the steamer Omaha landed a steam sawmill. The optimistic citizens build a new, three-story hotel. With a $10,000 price tag, it was then the largest and costliest in the state.[1] This dizzying optimism was a hallmark of the community, and it grew steadily. The 1880 census reported a population of nearly 860 people.[2] The great flood occurred as the town was shaking off the winter of 1881. On March 28 the river had been running high, but had fallen several feet by day’s end. But choked with winter ice, the river was unpredictable.[3]

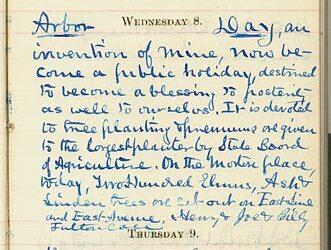

Flood at Niobrara. RG2118-5-14

Flood at Niobrara. RG2118-5-14

At midnight an alarm sounded that an ice gorge had broken. River water and ice poured into the town, and within half an hour had covered it with up to six feet of water, stranding its hapless citizens in the second floors of houses and stores.[4] With the onset of morning, boats were located and the task of rescuing the marooned began. Livestock and small animals, too, had been stranded by the sudden torrent, and by midday on March 29, they had been ferried to high ground.[5] The water remained high for two days, but by Thursday, March 31, it began to fall, and people slowly began to clean the ice and debris from their homes and businesses. On Friday, however, a telegram warning of flooding upstream convinced most of the townspeople to gather belongs and move to higher ground.[6]

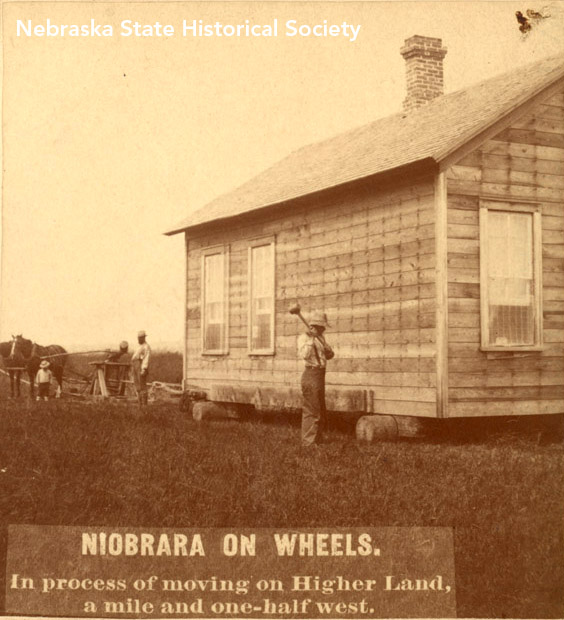

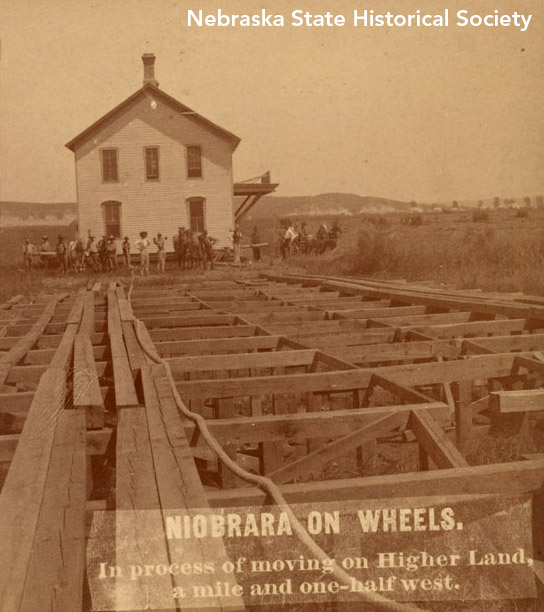

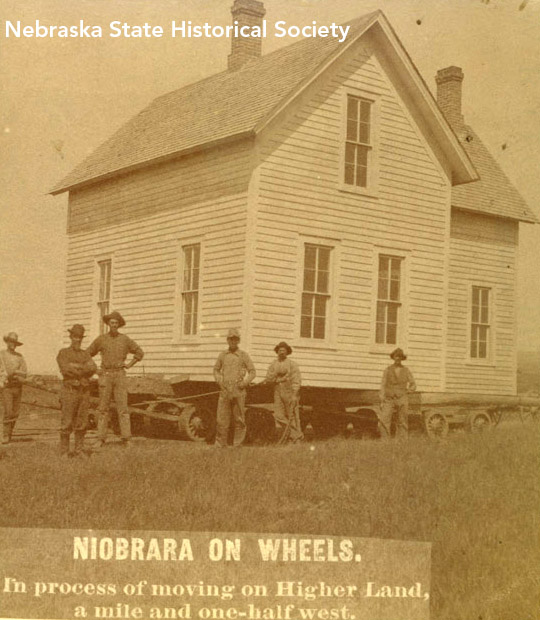

Niobrara on wheels. RG2118-5-19

Niobrara on wheels. RG2118-5-19

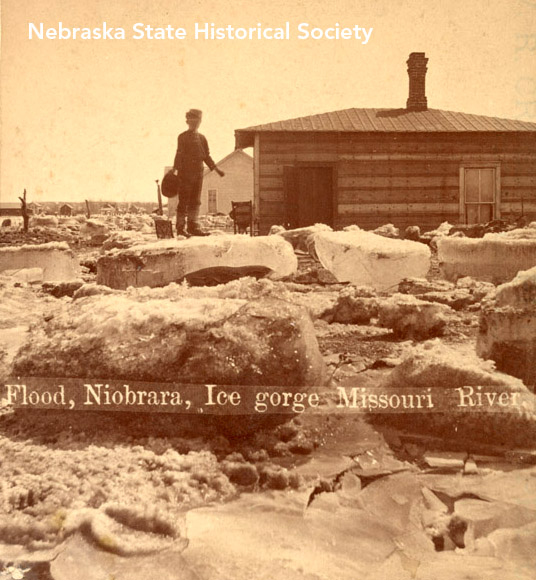

There were those die-hards, however, who chose to remain in town. Known as “stickers,” this group of thirteen young men took up residence in the second story of a store. To alleviate the boredom, the young men occupied the offices of the Niobrara Pioneer and published a tongue-in-cheek tabloid entitled The B’Hoys. In it they bemoaned the lack of food, the absence of women, and the general abundance of water. They also agreed to forswear the consumption of beans until such time as more private quarters could be found for sleeping.[7] April 1881 continued wet. By the twentieth of that month the river had flooded three times; washed out bridges, mill dams, and railroad lines; and caused thousands of dollars in damage.[8] While this flood was the first in the town’s twenty-four-year history, its effect had been chilling enough to convince the citizens to move to higher ground. But the decision to move was by no means unanimous. The land currently owned by people in the river bottoms would be substantially devalued by such a move, and the land on higher ground where the proposed relocation was to take place would inflate in value. The move would separate the town from the steamboat landing by about a mile, and the technological difficulty of moving a town of “three general stores, two drug stores, two hardware stores, a harness shop, two blacksmiths, five hotels, two livery stables, three physicians, a schoolhouse, …a church, [and] two newspapers” was formidable.[9] Judging from reports in the local newspapers, the discussions regarding moving were rancorous, and many people simply chose not to wait for consensus.[10] By April 22, 1881, the buildings were creeping up the grade to their new, drier location.[11] Benchland a mile and a half to the south and west of the old townsite was surveyed and platted.

Missouri River flood at Niobrara. RG2118-5-15

Missouri River flood at Niobrara. RG2118-5-15

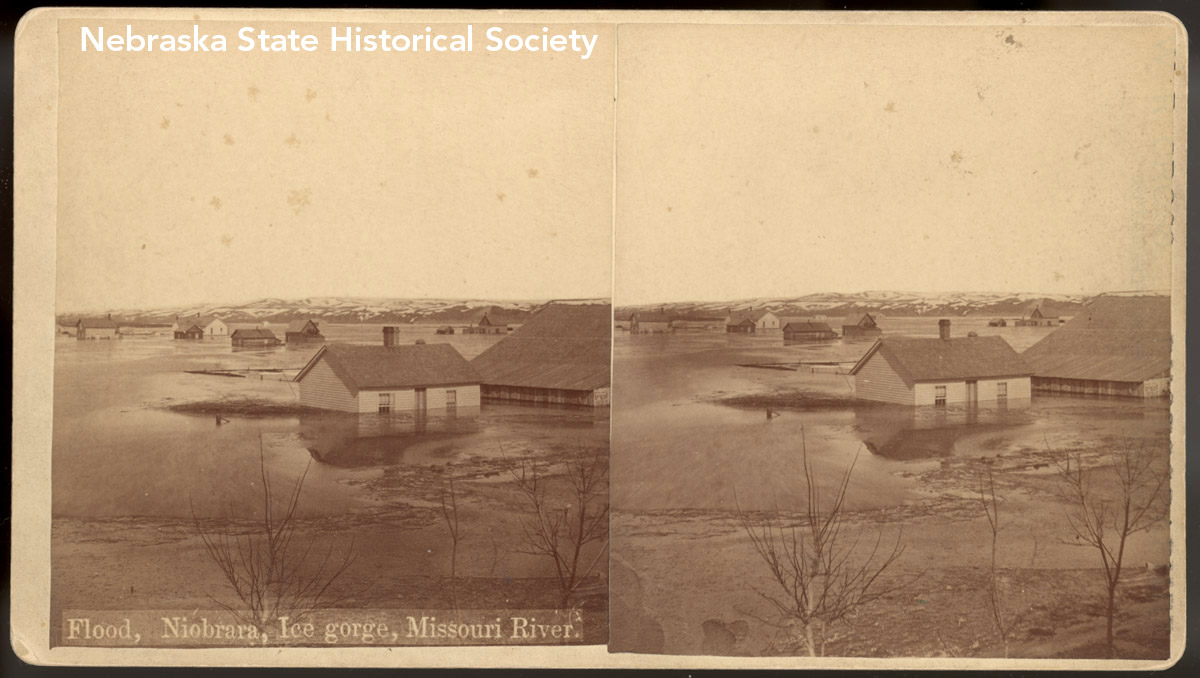

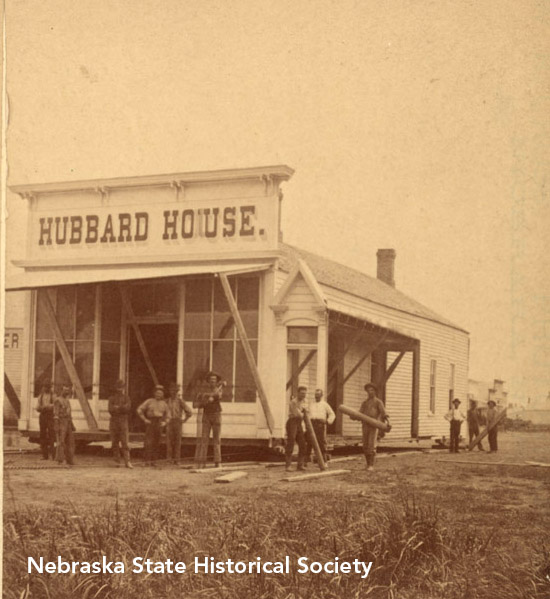

There is some evidence suggesting that moving the town was not entirely motivated by the flooding. Edwin A. Fry, editor of The Niobrara Pioneer, noted in March 1882 that Niobrara residents had grown tired of subsidizing streets and other improvements that increased the value of underdeveloped property being held for speculative purposes.[12] The flood provided an opportunity for Niobrara to rebuild on a new site, leaving behind the burden of unimproved town lots. B.Y. Shelley, founder and twenty-five-year resident of Niobrara (who probably owned some of the unimproved lots), became so disgusted with the plan to relocate the town that he left Niobrara and returned to his native Pennsylvania.[13] Teamsters, armed with house jacks, winches and capstans, block-and-tackles, beams, poles, oxen, mules, and horses began raising, bracing, and hauling building after building to the new Niobrara townsite. By January of 1882, all of the commercial buildings and most of the houses had been moved.[14] All that remained were some houses whose condition prevented their being moved, the county courthouse, and the post office.[15] The complications in removing the government structures was bureaucratic and political. The courthouse was forced to remain due to a statue which stipulated the manner in which a survey had to be made before a courthouse could be located. The survey of the new townsite did not comply with this law and had to be rectified before removal could take place.[16]

Moving Niobrara because of the Missouri River Flood. RG2118-5-20

Moving Niobrara because of the Missouri River Flood. RG2118-5-20

The relocation of the post office was a political issue. Edwin A. Fry, editor of the Niobrara Pioneer, was appointed postmaster of Niobrara in September of 1881, replacing J.C. Santee, who had held the position for about five years, and who edited the Knox County News, the Pioneer’s competition.[17] On September 28, Postmaster Fry wrote to the postmaster general, requesting approval of the move, as required by law. The request was ignored for nearly five months. Finally, Fry resorted to contacting Senators Alvin Saunders and C.H. Van Wyck to ask their intercession. Ultimately, the post office replied that the request had been delayed because the courthouse remained at the old location and more importantly, because Congressman E.K. Valentine had spoken in opposition to the removal.[18] Apparently, those who opposed the move caught the congressman’s ear and blocked approval of the move.[19] During the month of December 1881, Fry wrote three letters pleading with the postmaster-general to allow relocation. In one he noted that if it was not moved, a great inconvenience would result because the building in which the post office was located was scheduled for removal and there was no other space available.[20] One can imagine the delight that Fry’s rival, Santee, enjoyed at Fry’s dilemma. When, in desperation, Fry circulated a petition in support of removal, Santee was one of two men who declined to sign it.[21] The situation may well have proved fatal to Fry’s career as postmaster. In a terse note in the Niobrara Pioneer of February 10, 1882, he observed, “The [Niobrara] News folks gave a dance at Stein’s hall last Saturday night, about 30 couples being present. The occasion was in honor of Mr. Santee’s being reinstated to the postoffice.”[22] In all, the relocation of the town cost nearly $40,000. With it completed, the citizens of Niobrara settled down in their new location, confident of their security from flood.[23] In the May 6, 1881, issue of the Niobrara Pioneer, a tongue-in-cheek article entitled “New Niobrara” detailed tall tale plans for moving the town: “The latest scheme to be reported is one which is based upon the knowledge of the geological formations of the present townsite. The substratum is claimed to be quicksand saturated with water and it is proposed to build a dam across the Missouri near the mouth of Bazile creek. This will cause the water to back up, and, penetrating the quicksand, will float our present townsite and raise it up to the required height. Then props are to be placed underneath, and the water allowed to run in the old channel again. Failing in this it is proposed to anchor the town and then overflow it and keep it under water until about four feet of a sediment is deposited all over the flat, when the dam will be torn down and we will have a town still at least four feet higher than at present.”

A Niobrara house is being relocated. RG2118-5-17

A Niobrara house is being relocated. RG2118-5-17

The article was prophetic: When in 1952 the gates were closed on the Fort Randall Dam, upstream from Niobrara, the periodic flooding which eliminated sediment build up at the juncture of the Missouri and Niobrara rivers was ended. Then in 1956, the Gavins Point Dam was completed, creating Lewis and Clark Lake. The town of Niobrara, resting midway between the two dams, once again faced rising water due to the buildup of sediment at the mouth of the Niobrara River.[24] The groundwater rose an average of just under one-half foot a year until in 1972 it reached a level of 1,219.2 feet. The town of Niobrara was located about 1225 feet above sea level, which meant that most basements filled with between six inches and three feet of water.[25] In 1971 the townspeople faced three choices. They could sell their property to the Army Corps of Engineers and move to other communities, abandoning Niobrara altogether. They could build a system of levees and pumping stations in an attempt to lower the water table. Or they could move the town.[26]

Moving Niobrara because of the Missouri River Flood. RG2118-5-18

Moving Niobrara because of the Missouri River Flood. RG2118-5-18

In a poll held that year, ninety percent of the citizens voted to move the town. The plan called for the government to acquire the real estate in the old town, providing the residents with the capital to build their new homes and businesses. But what if only some of the residents moved? What would happen to the value of property in the new town if none of the businesses chose to relocate there? Over the course of four and one-half years the organizers of the project coaxed and cajoled the residents, and eventually a trickle of people began to move. Inspired by the show of confidence, the trickle became a flood, and the new town of Niobrara was dedicated on July 4, 1977.[27] The population was estimated at nearly 400, compared with 600 in 1970.[28] In contrast to the estimated $40,000 cost of the relocation of Niobrara in 1881-82, the project in the 1970s cost an estimated $14.5 million.[29] As the end of the old town neared, the State Historic Preservation Office, a department of the Nebraska State Historical Society, collaborated with the Historic American Building Survey and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to document the town, record its buildings, and salvage artifacts. By the spring of 1978, nothing remained standing in the second “old town” of Niobrara.[30] With its series of moves, Niobrara is both one of the oldest towns in Nebraska, and one of the newest.

John Carter worked for the NSHS for almost forty years. He served as photo curator, senior research folklorist and associate editor for the NSHS over his career. He authored several books and published numerous articles in both scholarly and popular journals. He was a scholar/consultant for many documentary films, including several produced by filmmaker Ken Burns. He was a well-known and much-requested speaker on almost any aspect of Nebraska. John was enthusiastic in his work and play, and had a deep and abiding love for the history and culture of Nebraska.

[1] Niobrara Centennial 1856-1956 (updated by Niobrara Bicentennial Committee, 1976),6. The article notes, “In 1867 the Episcopal Mission purchased this hotel from the Niobrara Townsite Co. and moved it to Santee for a church and Mission school. A tornado demolished it and a finer structure succeeded it only to be completely wiped out by fire.” [2] Niobrara Pioneer, Mar. 31, 1882, 1. [3] J. C. Santee, “Fearful Floods: The Big Muddy Gets on a Tear and Floods the Surrounding Country,” Knox County News, Apr. 7, 1881, reprinted in Niobrara Centennial, 17. [4] Ibid.; “History of Niobrara,” Niobrara Pioneer, Mar. 31 , 1882, 1. [5] Ibid. [6] Ibid. [7] The B’Hoys (Niobrara, Neb.), Apr. 4, 1881. [8] Niobrara Pioneer, Apr. 22, 1881, 2. [9] Knox County News, Apr. 7, 1881, reprinted in Niobrara Centennial 1856-1956, 17. [10] “Town Tumblings: The New Location Now Talked of by Many Citizens,” Niobrara Pioneer, June 10, 1881, 1; Ibid., “Niobrara Drainage,” June 3, 1881,8. [11] Niobrara Pioneer, Apr. 22, 1881,2 [12] Ibid., Mar. 3 1, 1882 [13] Ibid., Oct. 7, 1881. [14] “There are only about thirty buildings left in the old town now, and if the weather continues favorable many of those will reach the bench before the new year.” “Building Notes,” Niobrara Pioneer, Dec. 2, 1881, 8; Ibid., “Post Office Removal,” Jan. 6, 1882, I. [15] “Post Office Removal.” [16] Ibid. [17] The Post Office,” Niobrara Pioneer, Sept. 2, 1881, 4. Santee had been appointed postmaster in February of 1876 and held the post until he was removed for not being “in proper sympathy with the administration.” A. T. Andreas, History of the State of Nebraska (Chicago: The Western Historical Company), 1882, 1031. [18] Post-Office Removal,” Niobrara Pioneer, Jan. 6, 1882. I. [19] ‘This is probably because former postmaster John C. Santee, a staunch Republican, nominated E. K. Valentine for Congress. Andreas, History, 1031. [20] Niobrara Pioneer, Jan. 6, 1882, 1. [21] Ibid. [22] Santee was reappointed on Jan. 12, 1882. Andreas, 1031. [23] Ibid., 1030. [24] “Ground Water Problem at Niobrara, Nebraska and the Niobrara State Park,” draft report by the C.S. Army Corps of Engineers District, Omaha, May 1972. Nebraska State Historic Preservation Office Site File KX08, Nebraska State Historical Society. [25] Ibid., 5. [26] “Ground Water Problem,” 17-23; “Niobrara Relocation Featured in Magazine,” Niobrara Tribune, Mar. 3, 1977, 1. [27] Gordon E. Printz, “Relocation Passes Four Year Mark,” Niobrara Tribune, Jan. 13, 1977, Ibid., “2000 Attend New Town Dedication Ceremonies,” July 7, 1977, I; Ibid., Oct. 27, 1971; Nov. 24, 1976. [28] Niobrara Tribune, Nov. 24, 1976. [29] Ibid., Mar. 3, 1977. [30] ‘Town of Niobrara Relocation Project,” The Cornerstone, Nov./Dec. 1977, 1.