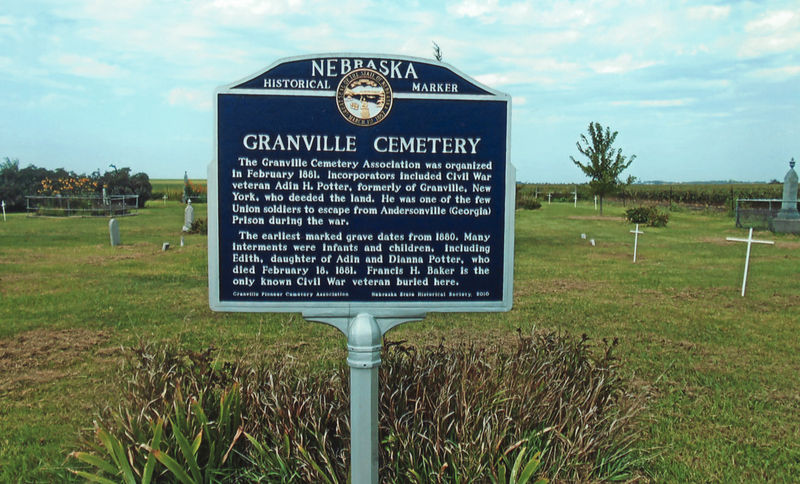

The playing of the national anthem, firing of muskets, and the shuffling of feet over the ground above him weren’t enough to wake Francis Henry Baker from his 117-year sleep. The commotion was caused by a ceremony dedicating the new historical marker at the 130-year-old Granville Cemetery southwest of Humphrey (between Norfolk and Columbus), where Baker and about sixty-five of his fellow pioneers are buried.

The playing of the national anthem, firing of muskets, and the shuffling of feet over the ground above him weren’t enough to wake Francis Henry Baker from his 117-year sleep. The commotion was caused by a ceremony dedicating the new historical marker at the 130-year-old Granville Cemetery southwest of Humphrey (between Norfolk and Columbus), where Baker and about sixty-five of his fellow pioneers are buried.

Their rest continues undisturbed, but the cemetery itself came back to life thanks to citizen members of the Granville Cemetery Association. Founded in 1881, the cemetery fell into disrepair decades later as people with ties to it left the area. In the mid-1970s, the land surrounding the cemetery was sold to an area farmer who put in a center-pivot irrigation system. It cut across a corner of the cemetery, which raised the ire of some area residents and descendants of the pioneers buried there. In 2000, a six-year court battle began that resulted in a judgment in favor of the revived Granville Cemetery Association.

The cemetery had come back to life. Now a fence separates the cemetery from the fields, and white crosses mark spots where it is believed graves exist. They surround the surviving stone monuments, many of which had fallen into disrepair and had to be restored.

Baker, who served in Company C, 8th Illinois Cavalry, during the Civil War, moved to the Humphrey area following the war. Once there, he worked as a harness maker and justice of the peace and married the daughter of fellow settlers James and Mary Tate. Baker died in 1894 and was laid to rest in the plot of land Adin and Dianna Potter had sold for a cemetery when their two-month-old daughter, Edith, died in 1881. Potter was also a Civil War veteran who relocated to the Humphrey area after the war.

When the Potters donated the land, concerned citizens formed the Granville Cemetery Association, so named because Adin Potter had hailed from Granville, New York. Over the years, more burials took place in the cemetery, including James and Mary Tate, whose stone is one of the few still standing. Eventually many of the people who had ties to the cemetery left the area. Markers fell into disrepair; weeds grew.

In late May 2011, around 100 people, including Civil War re-enactors, politicians, historians, and descendants of the pioneers gathered at the site to recognize the cemetery’s 130th anniversary, to honor the Civil War veterans and pioneers associated with it, and to dedicate a new state historical marker.

As winds whipped gray clouds across the sky, the people who played a part in restoring the cemetery told their stories. Among them was Mary Shott of Alliance, great-granddaughter of the Potters and Tates, who said she was surprised when Nancy Hartman called and asked if she would be willing to join the battle to save the cemetery.

“I didn’t know about my Tate grandparents until Nancy (Hartman) called,” said Shott, who added that she knew she had relatives living in the Humphrey area, she just didn’t know who they were or where they were buried.

Hartman, of Bellwood, spearheaded the restoration effort, which eventually included Brian Beckner, an attorney in Platte County. Because very few similar cases exist, this one set a precedent, Beckner said. “This case will protect cemeteries,” he added.

Following the speeches, members of the Harrison Camp Post Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War from Wisner fired a musket volley into the air. They stood just feet from Baker’s grave, which had been decorated with the symbols of war, including a musket, bayonet, canteen, haversack, and knapsack.

“There have been a lot of joys and frustrations,” Hartman said of the process. “I had people criticize me for what I was doing to the farmer—people who didn’t think it was wrong to run an irrigation system over a grave. (These pioneers) are a very important part of our history.

“They started the town, established the first schools and roads. They endured a lot, and we owe them our respect.” —Sheryl Schmeckpeper, NSHS Trustee