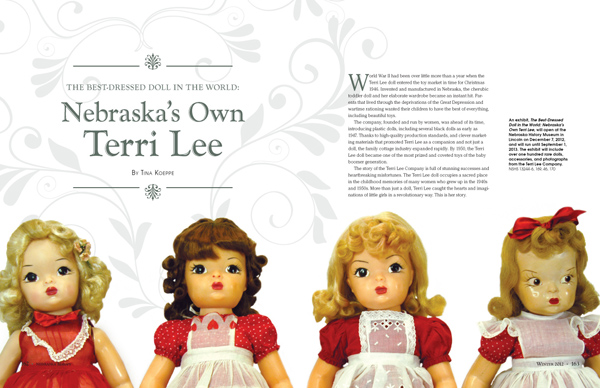

World War II had been over little more than a year when the Terri Lee doll entered the toy market in time for Christmas 1946. Invented and manufactured in Nebraska, the cherubic toddler doll and her elaborate wardrobe became an instant hit. Parents that lived through the deprivations of the Great Depression and wartime rationing wanted their children to have the best of everything, including beautiful toys. The company, founded and run by women, was ahead of its time, introducing plastic dolls, including several black dolls as early as 1947. Thanks to high-quality production standards, and clever marketing materials that promoted Terri Lee as a companion and not just a doll, the family cottage industry expanded rapidly. By 1950, the Terri Lee doll became one of the most prized and coveted toys of the baby boomer generation.

World War II had been over little more than a year when the Terri Lee doll entered the toy market in time for Christmas 1946. Invented and manufactured in Nebraska, the cherubic toddler doll and her elaborate wardrobe became an instant hit. Parents that lived through the deprivations of the Great Depression and wartime rationing wanted their children to have the best of everything, including beautiful toys. The company, founded and run by women, was ahead of its time, introducing plastic dolls, including several black dolls as early as 1947. Thanks to high-quality production standards, and clever marketing materials that promoted Terri Lee as a companion and not just a doll, the family cottage industry expanded rapidly. By 1950, the Terri Lee doll became one of the most prized and coveted toys of the baby boomer generation.

The story of the Terri Lee Company is full of stunning successes and heartbreaking misfortunes. The Terri Lee doll occupies a sacred place in the childhood memories of many women who grew up in the 1940s and 1950s. More than just a doll, Terri Lee caught the hearts and imaginations of little girls in a revolutionary way. This is her story.

The Terri Lee doll was born in the kitchen of a small house in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1946. Maxine Runci, a young sculptress from California, had stopped in Omaha to visit her parents at her childhood home on Chicago Street.

Maxine, the second oldest of Florence and Jacob Sunderman’s four children, had shown an early aptitude for art. After graduation from Technical High School, she attended Municipal University and worked at the Orchard and Wilhelm Department Store, where she was in charge of the doll hospital. Discovering that she loved repairing and working on dolls, she opened a doll hospital in her home, with her mother and sisters’ help.

Maxine desperately wanted to attend the Chicago Art Institute, but her father, a railroad worker, could not afford it. On July 12, 1936, The Omaha Bee-News published a cartoon drawn by twenty-one-year-old Maxine featuring Omaha’s seven county commissioners. An article that ran with the comic told about the aspiring young artist and how she worked at a department store to save money to attend the Chicago Art Institute.

The cartoon and article drew the attention of Omaha’s wealthy art patrons. Within a week, they raised funds to pay for four years at the Chicago Art Institute. Maxine excelled in her studies and focused on painting and sculpting.

After graduation, Maxine moved to Los Angeles, where some of her siblings lived. In 1943 while sketching portraits of soldiers at the famous Hollywood Canteen, she met a handsome Marine named Edward Runci. When his turn came to be sketched, he asked Maxine out on a date. They were married that same year. Edward’s artistic skill matched Maxine’s and the young couple embarked on a happy and creative partnership. The Runcis are best known for their glamour and pinup calendar art (sometimes with Maxine modeling), but also made names for themselves as painters of celebrity portraits. The Runcis’ only child, a daughter named Drienne, was born July 9, 1944.

In early 1946, Maxine worked as a sculptor, creating heads for high-end department store mannequins. For months, she experimented with a design for a small mannequin that children could dress and play with. She designed a prototype that she planned to take to the annual American International Toy Fair in New York City. There had been no Toy Fair in 1945 due to World War II and retailers and manufacturers alike were reportedly eager to attend the 1946 Fair. Maxine wanted to display her doll prototype at the fair, with the hopes of finding a toy company interested in working with her.

Maxine took the train from California to New York City. Her traveling companion was her nineteen-month-old daughter, Drienne. Maxine planned to drop Drienne off in Omaha for some quality time with grandma and grandpa while she continued solo to New York City. While staying with her parents, Maxine found inspiration in her daughter, Drienne. She worked at her parents’ kitchen table and sculpted a sixteen-inch clay version of the toddler, complete with chubby legs and little protruding tummy. She made a mold for the doll, created a plaster-of-Paris prototype, made a horsehair wig and painted a cherubic face on it. Maxine’s mother sewed a sunsuit for the doll. Pleased with the result, Maxine decided to also take this new creation, which she called her “toddler doll,” to the Toy Fair.

The entire essay appears in the Winter 2012 issue.