Interior of a class room at the Genoa Indian School. Students in class, sitting in desks and holding their books. Teachers are standing around the sides of the room. RG4422.1-20

“Nine o’clock taps and the wailing cry of the little boys as they stood under the sleeping porches with faces to the brick walls are two sounds that have always stayed with me.” Nebraskan Grace Stenberg Parsons remembered these sounds from the Genoa Indian School in Genoa, Nebraska. As the daughter of the blacksmithing instructor at the school, Parsons observed the young Native American children who attended the school on a daily basis from 1907-1911. A short memoir of her experiences can be found in the NSHS collections. You can read the full text here.

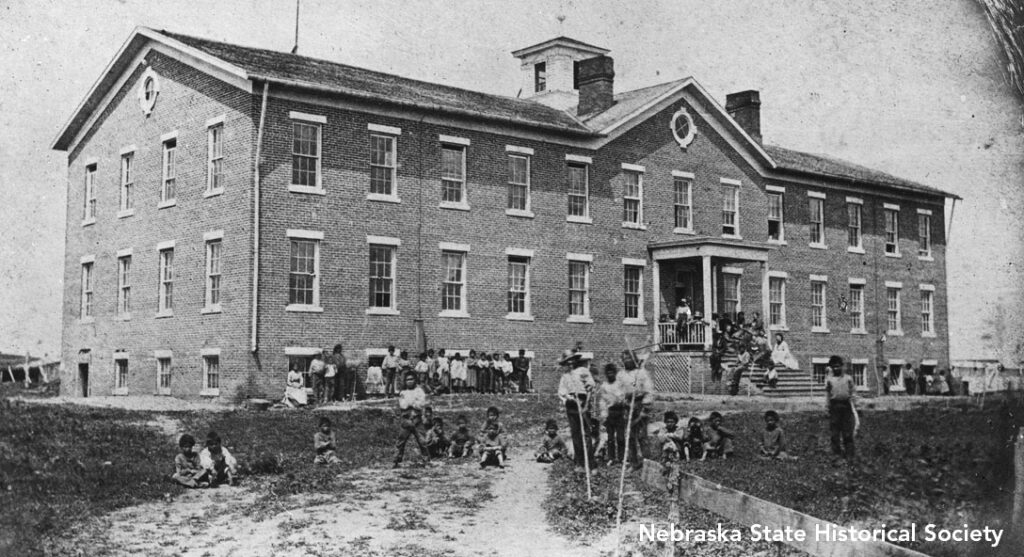

History of Boarding Schools General Richard Pratt, who led campaigns in the Indian Wars in the 1870s, founded the Carlisle Indian School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania in 1879. Pratt believed Native Americans needed to renounce their tribal way of life in order to become American citizens. He based his education program on his experiences as warden of an Indian prison. Pratt’s philosophy for teaching Native American children is now often defined as genocide. “A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one,” Pratt said in an 1892 speech. “In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” (qtd. in Bear). Other states also founded non-reservation schools, and at one time “the government operated as many as 100 boarding schools for American Indians, both on and off reservations” (Bear). Pratt’s philosophy of “killing the Indian” existed in all of them. Students who attended these schools were forbidden to express their culture. They were forbidden to speak their native tongues, and even given new “white” names. The schools were located far from reservation because Pratt and his contemporaries believed Natives would be “helped most by complete separation from their native culture” (2). The first students at Carlisle were Sioux children that were essentially hostages for the good behavior of their parents and Sioux leaders. The majority of children attending the school were Sioux, but Omaha, Winnebago, Ponca, Arapaho, Arikara, and Flathead children also attended. (Daddeiro 6) The Genoa Indian School was the U.S. government’s fourth non-reservation school. It opened on February 20, 1884. It grew from an initial enrollment of 71 students to an enrollment of around 600. It eventually encompassed more than 30 buildings on 640 acres.

Daily Life at Genoa Indian School Parsons described the arrival of the children to the school in her memoir. Children five years of age and up were eligible to attend school. During the first year, students ranged in age from seven to twenty-two years. All of them spoke Lakota (Daddeiro 2). “The little folks came in scared, dirty, and buggy,” Parsons wrote. “The clippers were waiting, all heads were shingled, they were bathed with carbolic soap from head to toe. At night they were dressed in long white night shirts and lined up. The matron watched while the captain called the roll, to each boy he would say, “Your name is Joe, your name Dan,” and so on until all had been accounted for. They repeated a short prayer in a monotone, said goodnight to their matron, then off to bed, some to sleep others to sob themselves to exhaustion. The little girls fared better than the little boys for the older girls mothered them. The little boys had only their matron and she was a busy person for she had many boys and many duties.” While the children were lonely, homesick, forbidden from using their own names, and unable to understand the language of their teachers, discipline was always enforced. “The school was run under military discipline,” Parson wrote. “The regiment was divided into companies. Each company had its captain, first and second lieutenants. The captains were responsible for the conduct of their companies. The boys and girls marched to and from the dining hall, to and from school. There was constant drilling either on the parade grounds or the gymnasium in preparation for the spring dress parades. The result was precision marching.”

Students spent half the day in classroom learning and the other half in vocational training. Parsons describes the average day for a Genoa Indian School student: “Six o’clock rising bugle, 6:30 bugle roll call and breakfast. Between 6 and 7:30, besides dressing and eating, the beds had to be made. Seven thirty whistle for all shop classes. School room classes started at 8:30 or 9. The 11:30 whistle dismissed the shops and classes. Back to the dormitories to get ready for 12 o’clock dinner. Bugle for company fall in and roll call then march to dinner. One o’clock whistle, shops and classes again. Class rooms dismissed at 4, the 5 o’clock whistle dismissed the shops. Three times a day the hospital took care of drops in the eyes, cuts, burns, and bruises besides the bed patients. The 5:30 bugle was for company fall in, roll call and supper. During the evening – band, orchestra and singing practice, gymnastics and track practice. Nine o’clock taps – all Indians in bed and lights out in the dormitories. Ten o’clock lights out for employees – power house closed down until morning. Of all the bugles we had I shall always hear taps. On a calm, mellow night the bugler would sound taps low and long, on a cold night it came quick and sharp, on a gusty night it came in snatches. However it came, to us it meant good night and lights out.” In between their structured activities, the students were also essential to keeping the school running. In the school’s early years, they were often kept so busy just keeping the school operating that their education was a second priority. Historian Wilma Daddario writes, “The amount of work done by the boys in the school’s first summer of 1884 was incredible. First, the land was cleared of weed and stubble. Corn was planted on 130 acres and cultivated six times. Forty-five acres were sown to oats, forty acres to hay, and twenty seven acres in potatoes and garden vegetables. The boys planted 3500 fruit trees, 3500 vines and plants, milked sixteen cows morning and evening, fed fifty-four pigs, and took care of all the horses and mules. The little boys, ages eight to ten, tended the garden” (5). Remarkably, there were only eighty-nine of them. Parsons describes the work of the girls, “The girls worked in the laundry, kitchen, dining room, and mending room. They were taught domestic science – how to cook and serve a meal in the home. During the summer they picked and canned fruit. They were trained as nurses in the hospital. The girls were taught to sew on sewing machines. The advanced classes made all the uniforms for the girls.” However, the girls’ domestic skills were centered around serving in a home, not managing their own private home. The curriculum reflects white attitudes that Native American children would grow up to be servants, not independent workers. Parsons seemed more optimistic about this attitude than the reality warranted, but she was also aware of the huge obstacles Native children faced once they left the school. “When they were graduated they were ready to accept a job but our white world was not ready to accept them as workers,” she wrote. “They had not kept pace with the Indians and his education so they refused to hire them. The heart-break came when the young people, not accepted in the white world, returned to the reservation to be met with rejection and ridicule. Only one thing remained – they were back in blankets and shawls – a disillusioned lot.”

Photograph of the Genoa Indian School Band visiting the Pine Ridge Reservation. Red Cloud is at the center facing sideways with a cane. RG1227.20-11

The Genoa Indian School tried to teach a liberal arts education, give the students vocational training, and maintain the quality of living at the school on an impossibly small budget – $200 per student per annum (4). Daddeiro writes, “A government report prepared in 1928 suggested that the per annum allocation per student should have been nearer $700 instead of only $200: ‘Boarding schools that are operated on a per capita cost for all purposes of something over two hundred dollars a year and feed their children from eleven to eighteen cents worth of food a day may fairly be said to be operated below any reasonable standard of health and decency.’” (10). A sample menu included rolled oats, bread, coffee, and syrup for breakfast; boiled beef, dumplings, mashed potatoes, gravy, bread, and water for lunch; and beans, rolls, gravy, and bread for supper. They “had butter two times a week and get milk practically every day” (5). However, even the school’s poverty was better than the poverty children faced at home. By the early 1930s, the conditions on the reservations were so dire that parents were sending their children voluntarily to boarding school. School officials had forcibly taken the children in the past. “They were not concerned so much about their education as they were about food and shelter,” Parsons wrote. Once the children left for school, parents and family members were not likely to see them again until the end of the school year. One of the longest-serving school superintendents, Sam B. Davis, felt that assimilation was the top priority of the school. Contact with family and the reservation did not fit with his mission: “His letters to parents were often condescending, paternalistic, and moralistic in tone. At times he would explain to the Bureau of Indian Affairs that he would not let a child go home, even after a family’s request, because he felt the parent, stepparent, or other relative was not acting in the child’s best interests” (Daddario 10). Even a child’s illness was not enough to warrant a visit from family members. Some could not afford the journey from a far-away reservation, but some were not even told that their child was sick. Trachoma, a contagious viral disease of the eye, was almost epidemic during the entire time the school was open. The lowest report was of 36 cases, or 24 percent of the students in 1890. In 1931, Mantoux tests for tuberculosis showed 71.9 percent of the students had a positive reaction. There were chicken pox, scarlet fever, mumps, and measles epidemics. Between 1884-1894, twenty-three students died (Daddeiro 4). If students were healthy enough, many of them ran away. Some returned to their reservations, and some were never found.

Young men and women of a graduate class at Genoa Indian School posed for a picture with their diplomas in hand. RG4422.PH000001-000024

Benefits However, the school did have two areas where it excelled: with the band and with its livestock breeding program. Superintendent Davis started a livestock breeding program in 1907. The school bred Percheron horses, Duroc hogs, and Holstein cattle. The animals won awards at the Nebraska and Kansas State Fairs as well as numerous other livestock shows. The University of Nebraska even sent representatives to Genoa to learn more about their successful breeding programs. The sale of the livestock added an average of $8,000 to $10,000 per year to the school’s financial resources. (Daddeiro 9) The Genoa Indian School band was so popular that it was invited to play at fairs and special events throughout the state. The band even welcomed presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan to Genoa in 1911. Parsons writes, “There were two bands, first and second for the boys, an orchestra for both boys and girls, also singing groups. So many people are amazed when I tell them that many Indians have a striking gift of voice and a general love of music.” These two activities along with boys and girls basketball, football, baseball, ice skating, class parties, and senior banquets display that life at the school was not complete drudgery. Students also returned to help current students celebrate events. Alumni of the school organized a “Returned Students” association and subscription to the school newspaper helped them keep in touch with former classmates. Some even came back for graduation. After they left the school, many returned to the reservation, where they farmed, ranched, or operated small businesses. Others went on to other Indian schools like Haskell in Kansas where they could earn a high school diploma. Genoa only offered ten grades until 1929. A handful attended nurse training, found teaching jobs, or worked at the industrial trades they’d studied. (Daddeiro 9) Parsons writes that, “Graduation week was our gala affair. The boys and girls were graduated from classrooms and the shops. There was open house that week. One full day was given to the shop displays and demonstrations. There were orchestra and band concerts, and dress parades. Dress parades like all military parades were spectacular and thrilling.” During World War I, many of the male students became soldiers instead of attending school. Seventy-four enlisted, and three students died in the war: “John Washakie, grandson of the famous Chief Washakie of the Shoshoni reservation, died of pneumonia. Silas Kitto and Horace Barse were killed in action” (Daddeiro 9). The years after World War I until the school’s closing on March 1, 1934, saw a range of personnel problems, including accusations that the superintendent was abusing students. However, there were examples of successful vocational and classroom teaching. The closing of the school, along with many other non-reservation schools in other states, was a result of changing sentiments in the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Director John Collier “favored the replacement of boarding schools with day schools and the alteration of curriculum to deal with rural conditions on the reservations. The reservation day schools were also intended to serve as community centers, where children and adults could learn as well as participate in native cultural activities” (Daddario 10).

Reunions The Genoa Indian School Foundation, with Humanities Nebraska, sponsors school reunions in the summer in Genoa. Alumni, descendents of alumni, and friends gather to celebrate Native American culture and talk about memories of the school. The most recent gathering was August 13 of this year. The event featured Native musicians, films about the Genoa Indian School, a scholarship presentation, Native American tacos, tours of the remaining Genoa Indian School buildings, and an ice cream social. It was the 27th reunion they’ve held. Parsons passed away in 1985 at her home in Grafton, Nebraska, after a long career as a school librarian in Columbus, Ohio. She and her husband participated in many service projects involving Native children throughout their lives. She was always a staunch supporter of education for Native children. “Good minds have emerged and been developed,” she wrote. “Until white man interfered with them, they were both clean of body and physically fit. Today beneath their poverty, disease and despair, the race is there – a wonderful race.”

Sources Bear, Charla. “American Indian Boarding Schools Haunt Many.” NPR.com 12 May 2008. Web. Daddario, Wilma A. “’They Get Milk Practically Every Day’: The Genoa Indian Industrial School, 1884-1934,” Nebraska History 73 (1992): 2-11. Print. Parsons, Grace Stenberg. “The Indians as I Knew Them.” NSHS RG1298. Print.