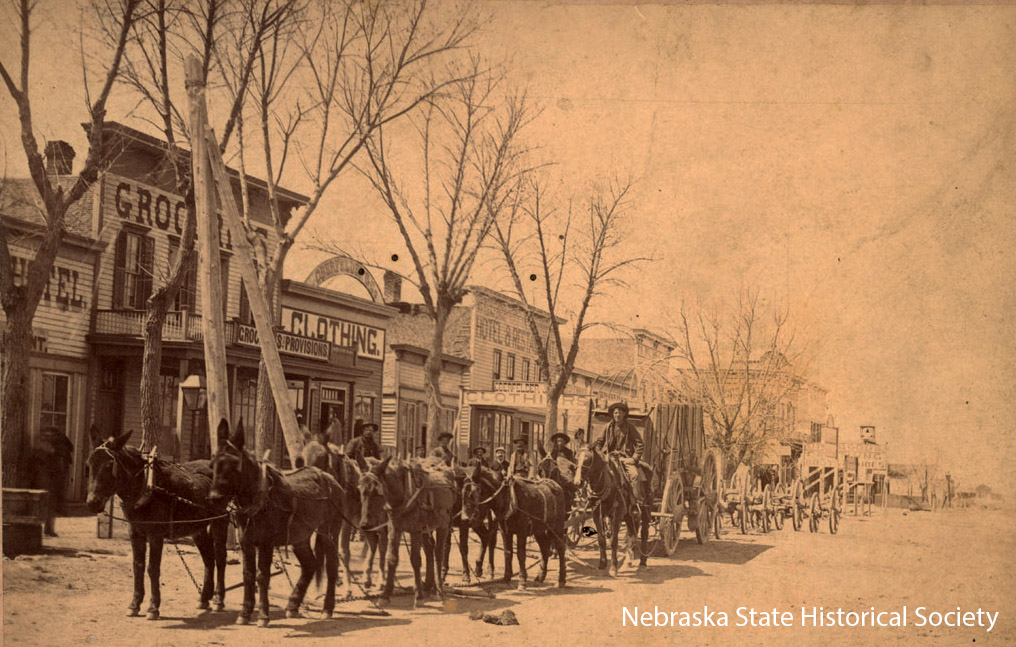

Sidney, Nebraska, circa late 1870s. NSHS RG3315-40

Sidney, Nebraska, circa late 1870s. NSHS RG3315-40

Associate Editor and black powder enthusiast Jim Potter wrote this blog post. One staple of TV or movie “Westerns” is a shoot-out in a saloon. Such confrontations are often portrayed as stemming from a volatile mix of drinking, gambling, testosterone, and readily available weaponry, which has a factual basis in the historical record. What the filmmakers can’t accurately portray, for obvious reasons, is that some of this gunplay took place in utter darkness. In the days when indoor lighting depended upon “open flame” lamps fueled by kerosene, manufactured gas, or even candles, the concussion produced by the discharge of handguns in confined spaces sometimes “snuffed” the lamps. This phenomenon became apparent from newspaper accounts of saloon shootings in western Nebraska during the 1870s and 1880s. At Sidney on April 22, 1879, blacksmith George Calkins and bullwhacker William Kane got into an argument after an all-day drinking binge. Calkins’s friend William May intervened, “but it did not leave Kane and May very good friends.” Later that evening in the Miner’s Hotel, the two exchanged words and a fight broke out. While Kane was pummeling May in the face, the latter shot Kane in the left arm. Fisticuffs continued as the two grappled on the floor. According to the Sidney newspaper, “This was all done in a dark room, as the lights were put out by the first report of the revolver.”

When large-caliber handguns, such as this .44 cal. single-action Colt revolver, were fired in a confined space, the concussion could extinguish open-flame lamps. This one takes the .44/40 cartridge, also used in many rifles and carbines of that era. That way an individual did not have to carry two types of ammunition. NSHS 8241-266

When large-caliber handguns, such as this .44 cal. single-action Colt revolver, were fired in a confined space, the concussion could extinguish open-flame lamps. This one takes the .44/40 cartridge, also used in many rifles and carbines of that era. That way an individual did not have to carry two types of ammunition. NSHS 8241-266

Little more than a year later, on May 29, 1880, “Patsy” Walters dropped by Doran and Tobin’s saloon in Sidney to find several men “having a jovial time drinking, joking, and singing.” One of them was a man named Smith, with whom Walters got into an argument and then called him “a damned thief. “Without further talk whatever Smith fired two shots, one ball taking effect in [Walters’] abdomen . . . . These two shots put all the lamps out save one over the bar. Before Smith fired the third shot Walters had got his six-shooter . . . . Smith ran behind the billiard table and witnesses of the affair claim that they fired almost simultaneously, Smith’s third shot and Walters first; that put out the remaining light.” Whether or not the room where the gunfire took place was frame, brick, or even canvas did not seem to matter, as long as it was a relatively confined space. Later that year, a soldier was mortally wounded in a tent saloon near the Camp Sheridan military post after gunfire blew out the lights. Once darkness had thus descended, additional shots were fired, some of them striking the soldier rather than the person for whom they were intended. The soldier died the next day after his leg was amputated. A fourth example of lamps being snuffed by gunfire also came from Sidney, this time on November 26, 1881. Two cowboys named James Jameson and Henry Coian had been drinking and got into what was thought to be a friendly wrestling match. Coian, however, struck Jameson over the head with his revolver causing an ugly gash. After Jameson had his head sewed up, he threatened to shoot Coian on sight and went to the O. K. Saloon for

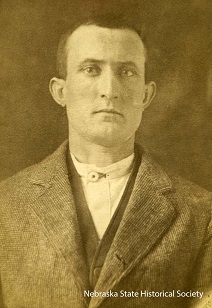

Harry Coian’s Nebraska State Penitentiary mug shot. At his March 27, 1882, trial in Sidney, he was convicted of second degree murder for killing Jameson and sentenced to life in prison. NSHS RG2418.PH0-641

Harry Coian’s Nebraska State Penitentiary mug shot. At his March 27, 1882, trial in Sidney, he was convicted of second degree murder for killing Jameson and sentenced to life in prison. NSHS RG2418.PH0-641

a drink. Coian spotted him there, burst through the doorway, and “without saying a word, drew his revolver and immediately began firing at Jameson, the concussion of the pistol extinguishing all the lights in the saloon. Coyne [sic] at this time ran out of the saloon, when the lights were re-lit and Jameson was found lying on the floor mortally wounded.” If darkness were not enough of a handicap, the firearms of that time used black gunpowder that produced clouds of smoke to linger in the room even after the lamps had been restored. Some years ago I decided to try snuffing open-flame lamps with gunfire to verify whether the historical accounts held up. I did the experiment in a small clubhouse owned by a shooting club, which had kerosene-fueled lamps for nighttime gatherings. They were the kind with glass chimneys. I had permission to shoot a black powder revolver in the clubhouse as long as I discharged the bullet through an open window. Putting a bullet hole in the wall seemed to be carrying the quest for authenticity a bit too far. The result of this experiment confirmed the historical accounts. Even with an open window that probably dissipated some of the concussion from the revolver’s discharge, the shot instantly snuffed out the lamps. More details about the nineteenth-century shootouts and my modern attempt to replicate their effect on open-flame lamps are in my article, “Shots in the Dark,” which appeared in the February 2001 issue of Roundup Magazine published by the Western Writers of America. After the article came out, a reader noted that the concussion phenomenon I identified may help explain a stanza in the Robert Service poem, The Shooting of Dan McGrew: “Then I ducked my head and the lights went out, and two guns blazed in the dark, And a woman screamed, and the lights went up, and two men lay stiff and stark.” — Jim Potter, Associate Editor of Nebraska History