After the United States entered World War I in April of 1917, President Woodrow Wilson appointed Herbert Hoover head of the U.S. Food Administration. Hoover believed that food would win the war and established specific days to encourage people to avoid eating particular foods in order to save them for soldiers’ rations and use overseas: meatless Mondays, wheatless Wednesdays, and “when in doubt, eat potatoes.”

Hoover also instigated a national campaign for greater swine production. He said in 1917: “We need a ‘keep-a-pig’ movement in this country-and a properly cared for pig is no more unsanitary than a dog.” In fact, said Hoover: “Every pound of fat is as sure of service as every bullet, and every hog is of greater value to the winning of this war than a shell.” Even suburbanites, he asserted, could help by raising hogs on domestic garbage as the Germans were doing. As a result of this campaign many patriotic cities repealed ordinances which forbade the raising of pigs within their respective limits, thereby enabling many of their citizens to raise their own pork.

The Lincoln Sunday Star on July 10, 1918, discussed the Hoover mandate on its society page, commenting: “Society has been told for the last few years that she must do her bit towards helping in this world war, but never before has she been told to do such a new and seemingly ridiculous thing as she has been told now. Last year we were all planting our potatoes and many a front yard that in former years had been given over to the raising of flowers alone, was changed into a veritable potato patch. Where people used to vie with each other as to the number and varieties of flowers they could grow, last year much rivalry was caused over the number of potatoes raised to the acre, and the number of acres or lots planted. . . .

“But just how many of us have given over a portion of our yards or lawns to the raising of pigs[?]. . . . Now the first thing I hear you say is that they are too dirty to have around, but they are not dirty, at least not dirty by preference. People have had the idea that they thrived better by leaving them wallow in the mud, but the only reason the pigs liked it was because they were not given a choice in the matter.”

The Star maintained that hogs wasted less and yielded more value to their owners than “other animals we think are so much nicer to have around,” and urged its readers with “a bit of available ground that is not being used for anything but flowers or nice green grass,” to “fence it off, build a sty or house or whatever seems to you to be the best thing to call it, and herein deposit Mr. Pig.”

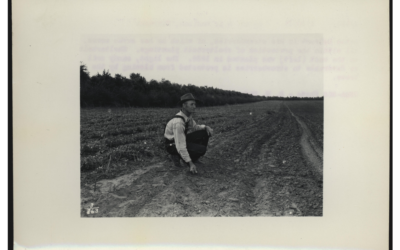

John Nelson’s photograph, dating from 1913 to 1915, depicted young Hilda Nelson with a pig named Polly. During World War I city dwellers were asked to raise pigs to increase the nation’s food supply. NSHS RG 3542.PH:020-01