In honor of Arbor Day, Nebraska History associate editor Jim Potter examines part of the political career of Arbor Day founder J. Sterling Morton. Some dramatic anti-J. Sterling Morton sentiments appeared in the May 23 issue of the Republican Nebraska Herald, published in Plattsmouth. Under the headline “Not Ashamed of It,” the article reported Morton’s recent speech in Plattsmouth when he had asserted that he was unashamed of his political record. The Herald noted that this was because “there is no shame in him.” The paper recalled that Morton had once stated that if Confederate States President Jefferson Davis deserved hanging, “Abraham [Lincoln] should be hung on the same tree, and that he would bear the same relation to Davis that the thieves did to Christ.” The Herald went on to say that Morton felt no shame for “having used his pen, his brain, and all his energies during the late struggle for national existence [the Civil War] against the government that protects him and under which he is now seeking office.” The article concluded that “loyal” Cass County Democrats “heartily despise the man [Morton] who would sacrifice their interests, the Nation, and, if necessary, his grandmother for his own political ends.”

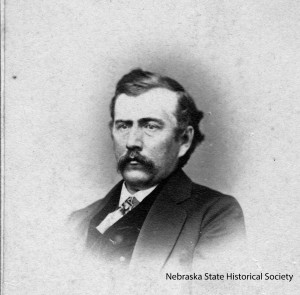

J. Sterling Morton in 1870. NSHS RG1013.PH1-8

J. Sterling Morton in 1870. NSHS RG1013.PH1-8

Whether or not Morton actually made the statement about Jeff Davis and Lincoln as the paper claimed, he had made his position clear on how he opposed giving the right to vote to African Americans. Nebraskans today most often remember J. Sterling Morton as the father of Arbor Day, a holiday he originated. Before and after that admirable undertaking, Morton was also one of Nebraska’s most partisan and polarizing politicians, particularly during the Civil War and the postwar years leading to statehood on March 1, 1867. Not only was he a fiery debater imbued with the principles that his Democratic Party had long held dear, his editorship of the Nebraska City News from 1865 to 1870 gave him a platform from which to express his views. “Politics in a democracy like this is a very dirty and unpleasant profession.” While this comment by Joseph Barker, Jr. of Omaha in a letter to his parents in England could well describe the 2016 presidential campaign, he was actually referring to Nebraska territorial politics in 1866. As Nebraska historian James C. Olson put it, “The press of each side struck out at each other in a fury of frenzied partisanship. The opposing candidates denounced each other with unbridled license.” While the nastiness associated with political campaigning doesn’t seem to have changed much over the last 150 years, the way politicians interact with the electorate or with each other certainly has. Lacking the option of “going negative” with advertisements or sound bites to be aired on television, candidates for office in 1866 attacked one another mostly through the newspapers. Instead of gathering at a central location to argue about issues for mass television audiences, candidates traveled around Nebraska Territory, sometimes in the same carriage, debating day after day in front of audiences in town halls or theaters.

One other major difference is the length of the campaign season; in 1866 the debates, party rallies, and newspaper commentary about election issues began barely a month before the election. There were several key elections in 1866. The first was held June 2 to choose state officers and members of a state legislature to take office when Congress approved Nebraska’s admission as a state. Also before voters that day was the approval of a constitution for the pending state. Although Morton and most northern Democrats opposed secession and supported the preservation of the Union through force of arms, they became highly critical of many measures the Lincoln administration invoked to help defeat the Confederacy. Foremost among them was the Emancipation Proclamation and the enlistment of African American soldiers in the Union army. The Democratic Party had long held that slavery was a matter that the U.S. Constitution left to the states, and with which the federal government had no authority to interfere through war or other means. Morton shared his party’s stance that the Civil War was being fought only to preserve “the Union as it was, and the Constitution as it is.” While Morton did not believe that ending slavery should be connected to the goal of putting down the rebellion and restoring the Union, the Confederacy’s fall brought that result. The ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 abolished slavery forever. Faced with this reality, Morton continued to resist granting political rights to the freedmen, specifically the right to vote and otherwise to participate in the political restoration to the Union of the former rebel states. These issues helped inflame the partisan battles in 1866-67 over the Nebraska statehood question in which Morton was a principal contestant as the Democratic Party’s candidate for governor of the new state. The Republicans (then going by the name of the “Union” Party) nominated David Butler for governor. The choice would be made at the June 2, 1866, election, although the winner would not take office unless the state constitution was also approved by the voters and then accepted by Congress and the President. During the month prior to the June election, attacks against Morton filled the columns of Nebraska’s Republican press and he responded in kind. In a May 21, 1866, letter to his Republican opponent David Butler, Morton stated his firm opposition to a bill recently passed in the U.S. House to prohibit federal territories such as Nebraska from denying the vote on the basis of race or color. He expressed this view more forcefully in a May 26 Nebraska City News editorial on the eve of the election: “The prominent issue now between the Republican and Democratic parties of Nebraska is Negro suffrage. This question has been hurled into the canvass by a radical Congress. Mr. Butler, the nominee for governor on the Republican ticket, endorses Congress fully. . . . Every vote for Butler . . . every vote for that ticket, is a vote for Negro suffrage in Nebraska . . . . A vote against the Democratic ticket is a vote in favor of Negro suffrage and for Negro equality.” The outcome of the June 2 election narrowly favored the Republicans, making Butler the state governor-elect, while the state constitution was adopted by a margin of only a hundred votes. Despite his loss in the governor’s race, Morton stood as a candidate for one of the U.S. Senate seats to be filled by the state legislature-elect when it convened for that purpose on July 4, 1866. Because the Republicans had also gained a legislative majority in the June 2 election, Morton’s goal of being tabbed a senator was doomed. Two Republicans were named as U.S. Senators-elect. Hopes for the prompt admission of Nebraska as a state, now that officers had been elected and a constitution approved, were soon dashed by President Andrew Johnson’s pocket veto of the admission bill. Congress would have to start over with a new Nebraska statehood bill when the next session convened in December.

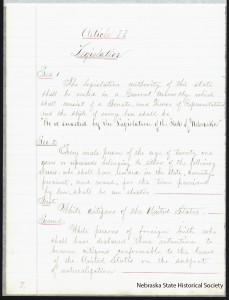

Before admitting Nebraska as a state, Congress insisted that the Nebraska Legislature nullify the State Constitution’s provision that permitted only white men to vote. NSHS 8769-6-(1)

This time the clause in the Nebraska Constitution that limited voting to white men would not go un-noticed, sparking Congressional resistance that would further delay statehood until the Nebraska legislature nullified the restriction in February 1867. During debates over this contentious issue, Morton did not waver in his opposition to granting black men in Nebraska the right to vote. In the end Nebraska lawmakers voided the “whites only” language in the constitution, whereupon Congress passed the statehood bill over the president’s veto and Nebraska was proclaimed a state on March 1, 1867. On April 1, 1867, James Walker of Plattsmouth became the first known African American to cast a ballot in Nebraska when he voted in the city election. Sterling Morton was also the Democratic candidate for governor of Nebraska in 1882, 1884, and 1892, with the same result as in 1866. His long affiliation with the Democratic Party and his outspoken stance on slavery, race, and the Lincoln administration’s wartime policies limited his vote-getting ability in an electorate that included many former Union soldiers. He later served as Secretary of Agriculture by President Cleveland from 1893–1897, and is remembered today as the founder of Arbor Day and promoter of modern agricultural techniques. But whether or not Morton would have sacrificed his grandmother for his own political ends, his legacy of racism and polarizing politics is just as important to remember as his positive influences on the state. — Jim Potter, Associate Editor of Nebraska History