“A real-life Jersey Boys story played out in Omaha six decades ago that revolved around athletics and academics, with a little bit of singing mixed in,” writes journalist Leo Adam Biga in the Summer 2023 issue of Nebraska History Magazine. From the 1950s through the early 1970s, an informal “pipeline” lured student-athletes–mostly Black–from New Jersey and other eastern states to what is now known as the University of Nebraska at Omaha. “When opposite cultures from the East and Midwest collided, something unexpected happened: Unity.”

We’re posting Biga’s article from the magazine below (or read the print-layout PDF here .) History Nebraska’s “Household-Plus” members receive four issues of Nebraska History Magazine per year.

Since this article went to press, we were saddened to learn of the death of actor, Omaha native, and UNO alum John Beasley, who is quoted in the article. Leo Adam Biga also recently wrote about Beasley for Flatwater Free Press.

East Coast-Midwest Connection that Forged Unity Decades Ago Still Binds Participants Today

By Leo Adam Biga

Sam Singleton in the 1964 Tomahawk yearbook and in a recent photo. Now living in Virginia, Singleton still performs as a singer.

A real-life Jersey Boys story played out in Omaha six decades ago that revolved around athletics and academics, with a little bit of singing mixed in. When opposite cultures from the East and Midwest collided, something unexpected happened: Unity.

Powerful examples of diverse people uniting for a common cause happen in athletics. A little known story of disparate student-athletes coming together as one played out at the University of Nebraska at Omaha from the late 1950s through the early 1970s.

Dozens of young men from the Eastern Seaboard like Sam Singleton made their way halfway across the country to the then small municipal Omaha University, which competed at the NAIA or small college level during that era.

These working-class urban kids, white and Black alike, were drawn from New York, New Jersey (Singleton), and Maryland as well as from other states such as Ohio by the lure of scholarships that paid for part of their education and prepared them for careers. Before they arrived they considered Nebraska the boondocks, but once settled here they enjoyed its low cost of living, relaxed pace, and friendly residents. Many brought accents and attitudes born of their Eastern, streetwise roots and yet they found acceptance from teammates and classmates, the majority of whom were local kids, although some hailed from the greater Midwest and the South.

Interviews with participants in this life-changing experience that blended individuals from distinct parts of the country with different lifestyles reveal positive memories about the experiment.

Coming out of high school back East, the recruits faced dim prospects for attending a four-year college owing to meager financial resources or average grades or higher education not being a priority in their families. Few were even recruited by area schools, overshadowed by higher profile peers in that talent-rich region. Black student-athletes like Singleton faced extra barriers. Predominantly white schools only accepted a small quota of African Americans. Historically Black colleges were not even on the student-athletes’ radar since HBCUs were nowhere near them.

When the opportunity presented itself to get a scholarship to a university 1,500 miles away, Singleton and other student-athletes jumped at the chance. They weren’t sure how they would be received. The warm welcome by the university and the community surprised them.

Singleton has come to call the experience the East Coast-Midwest Connection. He spearheads a project by that name which endeavors to share the experience in a book and documentary. Gratitude motivates Singleton to want to share the story of how student-athletes combined to create something bigger than themselves. Like many of his fellow participants, he credits the growth opportunities afforded by the experience with setting him up for success in life.

The Connection has its origins in the 1959 recruitment of Barry Miller from Mountain Lake, N.J. by then-UNO head football coach Lloyd Cardwell and head baseball coach Virgil Yelkin. Miller earned baseball All-America honors as a record-setting pitcher and was drafted by the Milwaukee Braves. His success triggered a domino effect as the “Jersey Boys” brought word back that Omaha was a good landing spot. Another East Coast native who became an ambassador for the connection was Wayne Backes, who played football and baseball for OU in the early ’60s.

Lloyd Cardwell, head football coach 1947-1959. In 1959 Cardwell and baseball coach Virgil Yelkin successfully recruited Barry Miller from Mountain Lake, NJ. Miller’s success in Omaha triggered a domino effect among New Jersey athletes. UNO Libraries’ Archives & Special Collections

“Once it starts, you get a guy and then you get another guy, and then sight unseen more guys would go there on word of mouth,” said retired UNO Sports Information Director Gary Anderson.

When Cardwell retired, successor Al Caniglia parlayed those earlier inroads in the fertile athletic territory of the East and more recruits followed. So many that a veritable pipeline fed a steady stream. Even non-athletes got in on this Go West Young Man rush. The more that came, the more appealing it was for others to follow and the less new arrivals felt like fish out of water.

The athletes among them were variously recruited to play football, basketball (Singleton), or baseball. Some came to wrestle and others to compete in track and field. Some competed in multiple sports. The late Don Benning, the university’s first full-time Black faculty member who was also an assistant football coach and the head wrestling coach, played a key role, too, in getting and keeping recruits there. A few earned All-America honors and an even more select few went professional.

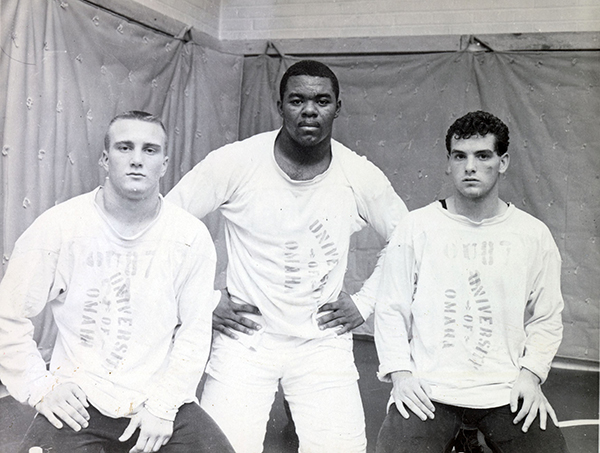

Don Benning, head wrestling coach and assistant football coach, was the university’s first full-time Black faculty member. UNO Libraries’ Archives & Special Collections

Most earned a degree and returned to their old stomping grounds. Others, like Singleton, stayed and married local girls, making careers and raising families in their adopted hometown. During their time together, this confluence of Eastern and Midwest sons forged connections and friendships that still endure. Each group influenced the other, not just on campus or on playing fields and courts, but in the community. Black student-athletes like Singleton lived on the Near North Side, where they enjoyed their culture. All speak fondly of the shared experience and the impact it made in shaping them.

The East Coast-Midwest Connection was part of transformational changes at the school that diversified its student ranks and engaged the university with more sectors of the community. The Bootstrapper, Goodrich, and International Studies programs, along with the Department of Black Studies, the Center for Afghanistan Studies, and the Office of Latino and Latin American Studies, were pivotal developments in moving the school from its parochial, white-centric focus to a more inclusive, multicultural stance. The informal East Coast-Midwest system was no less impactful in broadening the horizons of everyone who intersected with it.

Those who participated in this convergence of cultures agree the experience marked a milestone in their lives. They came as rather immature, rough around the edges boys and left as grown men of character. They still carry the bonds and lessons forged then, which they feel have something to offer the nation and the world. Just as they received much from the college and community that took them in and set them up for success, they paid it forward by becoming productive citizens. Their accomplishments range across many industries. Some have even gained national recognition.

Jersey Boys

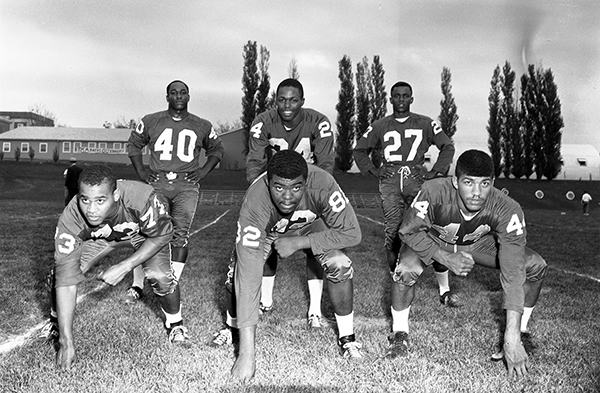

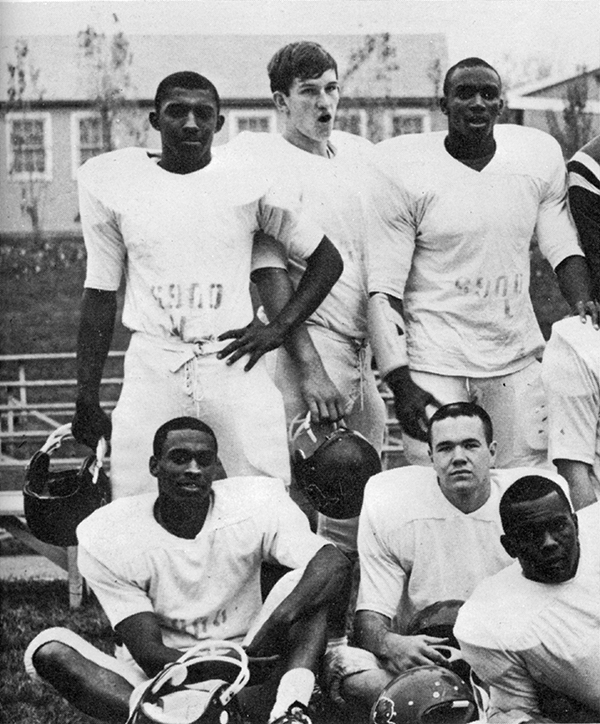

Some of the members of the 1963 Omaha University football team. Front: William Shepard (73) of Lincoln, Jimmy Jones (82) of Morristown, NJ, and Gerald Allen (44) of Massilon, OH; back: Art Reynolds (40), Omahans Roger Sayers (24) and freshman quarterback Marlin Briscoe (27). Courtesy of UNO Libraries’ Archives & Special Collections

Sam “Swish” Singleton was among the cadre of student-athletes from N.J. who ventured to Omaha. He came in 1963. This preacher’s son from South Carolina became a high school hoops star in Morristown, which led to him getting a scholarship to showcase his game in Omaha. The school lacked dorms then and northeast Omaha was the only part of town where African Americans could rent rooms. Coach Don Benning, a product himself of North Omaha, arranged for out-of-state Black student-athletes like Singleton to board with widows and empty-nest older couples in the heart of the Black community. Singleton boarded with football players Jimmy Jones and Billy Barber in the home of Dora Green.

“A number of us came to an unfamiliar area of the country to live and assimilate in a central area under the tutelage of families and professionals in that community,” said Singleton. “Here we were living in boarding houses as we went to college, following the people’s rules and regulations—can’t bring no girls in there, can’t do this or that. We were part of their extended family for those four years. To be able to come to another part of the country and be accepted and given that nurturing was invaluable.”

For some perspective, Singleton’s time in Omaha (he left in 1976) paralleled the emergence of eventual state senator Ernie Chambers, the outbreak of civil disturbances that left North 24th Street a shambles, the formation of the school’s Black Studies department, and increasingly tense relations between the Black community and law enforcement. Redlining made Omaha a segregated city and it was still in effect when Singleton lived there.

Described as a “go-getter,” Singleton used his playground-honed basketball skills, sweet singing voice, and gregarious personality to ingratiate himself on campus and in the community. In addition to intimate friendships made with fellow transplants, he immersed himself in such local touchstones as the Fair Deal Café, Skeet’s Barbecue, and Kellom School, where he played pickup ball with native Omaha greats Bob Boozer, Ron Boone, and Bob Gibson.

Ironically, he said, he learned more about African American culture and community in segregated Omaha than he did back east with its larger Black population. In Omaha, the birthplace of Malcolm X, he was exposed to activists and leaders who overwhelmed him with social, political ideas that “influenced” his own thinking. Among other things, he learned that “racism is real but it doesn’t define your opportunity.”

“I owe all of my development as a man, as an athlete, as an entertainer, as a music promoter and as a professional to Omaha. I consider Omaha the place I grew to be a man. I came when I was 19. I left when I was 37. Omaha is still my home away from home.”

Hackensack, N.J. native Dominick “Dom” Polifrone, who played football at OU from 1966 to 1969, said Sam personified the cool groove sensibility the newcomers brought. “We brought a lot of different flavor, a different way of culture. I can still picture Sam and some of the guys singing doo-wop in the hallways.”

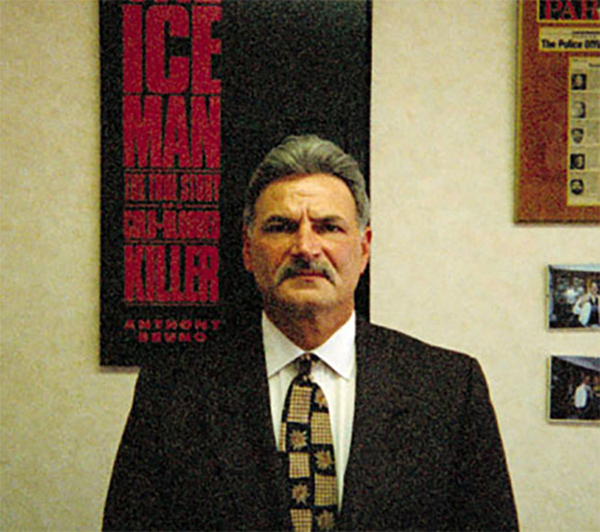

Dom Polifrone went on to a distinguished career in law enforcement, including undercover work as a special agent of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. UNO Alumni Association

Omaha native Toby Bloom shared an apartment near campus with Jersey guys, including wrestler Bruce “Mouse” Strauss, whose later exploits as a professional boxer landed him on the David Letterman show and inspired the movie “The Mouse.”

“They were some colorful and interesting guys that had their own vernacular and brought some East Coast flash and style to Omaha,” Bloom recalled. “I remember the ‘Jersey Boys’ that were at OU at the time and had fun socializing with them,” said Carol Bottorf Eggers.

Great Athletes

In terms of athletics, the new arrivals variously made their college marks in football, basketball, baseball, wrestling, and track and field. Polifrone was part of a strong football contingent from the East and from OU’s own backyard. He played with such “great athletes” as Jimmy Jones from Morristown, N.J., Gerald “Jerry” Allen from Massilon, Ohio, and the late Marlin “The Magician” Briscoe from South Omaha.

On the train that first brought Polifrone to Omaha, he despaired at all the farmland he viewed, sure he’d made a mistake coming so far from home and to such unfamiliar surroundings. Not a building or deli in sight. He’s forever indebted to a Creighton University priest traveling in the same coach car who noticed his distress and counseled him to stick it out to Omaha. The priest even introduced Polifrone to head football coach Al Caniglia. The scared recruit became an All-American linebacker at OU. Polifrone heeded advice from then-Omaha deputy police chief Al Pattavina to pursue criminal justice studies. The decision set him on the path for a distinguished law enforcement career.

The late Jimmy Jones came to the attention of OU, where he was a scholarship anchor at offensive tackle and defensive end all four years. He even played some tight end his senior year and led the team in receptions. He was drafted by the AFL’s New York Jets. Though injuries prevented him from taking the field in a Jets regular season game, Jones worked in the franchise’s front office through its historic 1969 Super Bowl win. He later moved onto a long corporate career that included serving as senior vice president and chief human resources officer with Reebok International.

After serving four years in the U.S. Air Force, Jerry Allen burst on the scene as a record-setting two-way star for Omaha. He played with the NFL’s Baltimore Colts and Washington Redskins.

New Jerseyite Tony Gervanzio found the talent he joined in Omaha eye-opening. “In your own little backyard you think you’re pretty good. You get to college and you find out everybody’s real good. It’s an awakening. You learn to eat humble pie real quick.”

Gervanzio and others followed the lead of fellow Morristown native Wayne Backes, who went ahead and stamped himself a standout in football and baseball at Omaha.

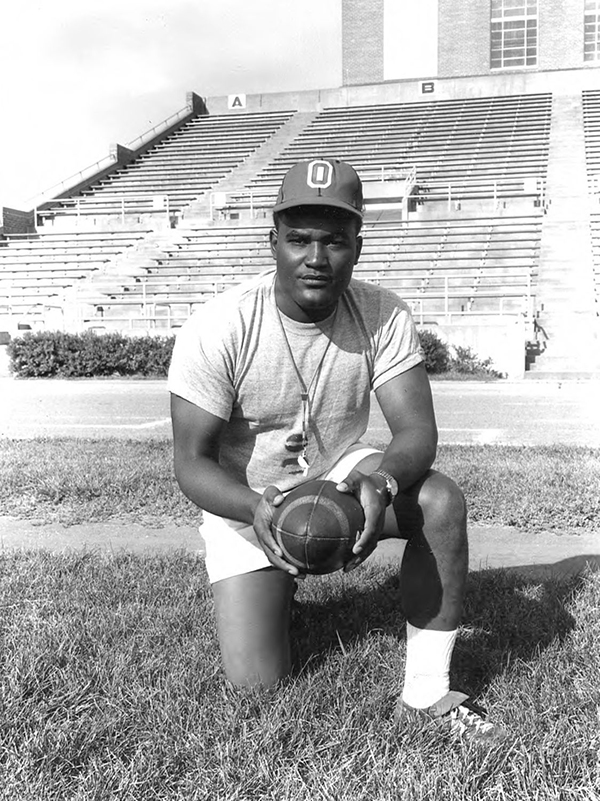

Perhaps OU’s most talented gridiron performers were hometown sons Roger Sayers and Marlin Briscoe. Sayers, the older brother of NFL Hall of Famer Gale Sayers, was a world-class sprinter, twice beating the “Human Bullet” Bob Hayes in races. Dubbed “The Rocket,” Sayers set long-standing school records as a track sprinter and as a football halfback-return specialist.

When no other college coach wanted Briscoe as a quarterback in an era when Blacks were rarely given the opportunity to be the signal-caller, Caniglia did. The coach even sent his out-of-state stars, Allen and Jones, to seal the deal.

“Jerry and Jimmy came over to my house to pretty much recruit me. They were quite persuasive,” recalled Briscoe. Caniglia kept his word and Briscoe became a record-setting All-American signal-caller during a 1965-1968 career that saw him earn the nickname “The Magician” for his explosive running and throwing and for leading dramatic comebacks.

The wrestling program under Don Benning ultimately became the biggest beneficiary of the pipeline with All-American performers Reggie Williams (Jersey), brothers Mel and Roy Washington (New York State), and Bruce “Mouse” Strauss helping make OU a dynasty that culminated in a national championship. The Washingtons made Omaha home and they made community contributions.

“Piece by piece it finally came together,” Briscoe said of the pipeline.

High-flyers

Relationships superseded cultural differences, Singleton said. “The university and the community embraced us. As student-athletes from different backgrounds we all bonded together with one common denominator—getting a college degree to help us go on and do better things in life. We all ended up having high achievements in life.”

Start with Singleton. The Seattle Supersonics selected him in the NBA draft. While he never played in the NBA, he did compete in the Eastern Professional Basketball League, comparable to the present-day NBA G League. Like many of the East Coast athletes, he married and lived in Omaha for many years. He worked as the employee assistance director at the Western Electric plant. He later relocated his family back to the East Coast where he continued his career in corporate and nonprofit management. One of his most successful accomplishments was as executive director of the Madison Square Boys and Girls Club of New York.

Singleton became such a fixture in the Omaha music scene, performing with local bands, which led to his induction into the Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame. Even though he no longer lives here, he has maintained close ties to the city, where he often returns to perform.

Gary White was another Morristown native recruited to play football. After getting his business degree he married an Omaha gal and the couple stayed and raised a family while he pursued his career. He worked in admissions at UNO and then at the College of Saint Mary, where he helped grow the school into one of the Midwest’s top private women’s colleges. He later changed careers to work for Commercial Federal Bank. He became active in the Greater Omaha Chamber of Commerce and with charitable causes.

He was not serious about academics when he first arrived, but as his studies took precedence he knew football was not in his plans.

“Many friends from Jersey and Omaha mentored me and served as role models, including Rev. William Johnson of Omaha. The more I began aligning with Omaha people, the more I realized the life there was good and there were many opportunities. It is hard to explain, but I would say had I stayed in New Jersey I would never have been as successful as I was at the college and in Omaha. Many others who made the move from the East to Omaha were successful. It was a great experiment and experience.”

The late Harold Dow and his brother Jimmy Dow heard about this Midwest opportunity from the fellas in Hackensack and followed the caravan west. Neither were athletes. Harold proved the right person at the right time in the right place when network affiliate KETV sent word to local colleges and universities it was looking for Black talent. His fine speaking voice, high intelligence, and writing ability got him hired. He read news on air his first day on the job, making him the first Black reporter to broadcast in Nebraska. Breaking the color barrier was too much for some viewers, who flooded the station with complaints. There were even some death threats. He continued reporting and his work caught the attention of CBS, where he was a national correspondent for decades. Brother Jimmy became an attorney and a judge in his home state of New Jersey.

Upon graduating, Polifrone returned East to work as a criminal investigator with the Bergen County (N.J.) Prosecutor’s Office before joining the Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms. His federal undercover work helped bring down the notorious contract killer Richard “The Ice Man” Kuklinski. Since retiring, he’s served as director of the Hackensack Board of Education. He mounted a bid to become Bergen County sheriff.

Many Omaha natives who competed, studied, and partied with the “Jersey Boys” also went onto success. John Beasley, who played football for the Indians (now the Mavericks), has forged a career as a stage, film, and television actor. He operated his own theater in Omaha for several years. He enjoyed the camaraderie of the “fellas” who came as part of the East Coast Invasion. He’s a co-star in two beloved sports movies, “The Mighty Ducks” and “Rudy.” At age 80 he has a leading role in a Broadway-bound production of the musical “The Notebook.”

“We didn’t look at them as the guys from back East,” Beasley said. “They adopted Omaha and Omaha took them on in, man. The Near Northside district where the Black guys from back East lived was a really good place to be. That was my neighborhood, too. We were poor, but we had our spots, man. It was a good, close-knit community, and those guys fit right in.”

Roger Sayers went on to an executive corporate career at Union Pacific. He was the City of Omaha’s human relations director. Upon retiring from U.P. he became a Salem Baptist Church trustee.

The late Marlin Briscoe made history with the Denver Broncos as pro football’s first Black starting quarterback, thus breaking a color barrier that eventually opened the door for today’s bevy of Black signal-callers. But after one season successfully playing QB with the Broncos, Briscoe was denied the chance to play the position again. Undeterred, he converted to wide receiver, earning All-Pro honors with the Buffalo Bills before winning two Super Bowl rings with the Miami Dolphins. He developed a serious drug addiction, but after beating it, he served as executive director of the Long Beach (CA) Boys and Girls Club. In 2016 he was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. Several East Coast-Midwest colleagues were there to share the special moment. The NFL Hall of Fame is still a distinct possibility. Briscoe has been the subject of a book and national media stories. His old teammate John Beasley is developing a dramatic feature film telling his saga.

Another hometown kid made good, Curlee Alexander, was an All-American cog in the OU wrestling program. After graduating he became an assistant coach under Don Benning. Later, Alexander found great success as head wrestling coach at his old high school, Tech, before building a dynasty program at Omaha North High.

Lloyd Williams considers himself fortunate for meeting these and many other individuals upon coming to Omaha from back East. They exemplified high character. Some, like Billy “The Wolf Man” Barber, were real characters.

Williams grew up in mostly white Camp Dennison, Ohio, and was the only Black student in his high school, where he was a football sensation, so coming to Omaha and boarding in “the ghetto” posed “a culture shock.” He adapted and thrived, as did his Eastern mates. He actually ended up making Omaha his home.

“My father got sick in 1969 and I had to drop out of college to be with my family. I returned in 1971 and married a young lady out of Omaha. I obtained a good education from OU and ended up having a decent career there with Mutual of Omaha. We stayed until 1986, living a good life. We relocated out West, to Las Vegas, because I couldn’t take the winters anymore. Otherwise, we’d still be there.”

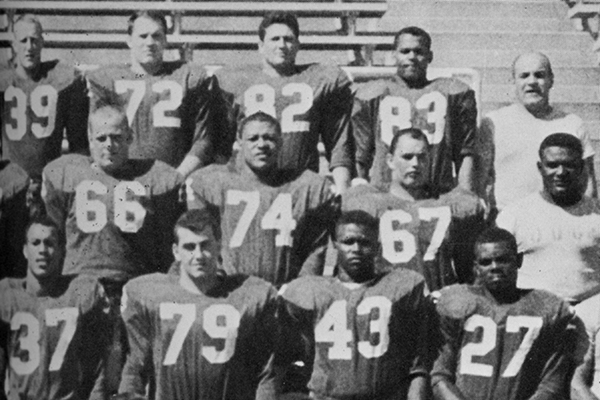

Lloyd Williams, top left, with the 1965 football team. Williams was the only Black student in his high school in Camp Dennison, OH; coming to Omaha and boarding in a Black neighborhood posed “a culture shock.” Williams ended up making Omaha his home. 1966 Tomahawk

Not the color of your skin, but the content of your character

Black students like Williams didn’t only fraternize with other Blacks. White students like Polifrone didn’t only hang with whites. Color didn’t matter to this cohort, who played cards, hoops, and billiards and chased girls together. For Roger Sayers, who grew up in heavily segregated Omaha, the interracial bonding represents a real “human interest” story of harmony in contrast to “all this turmoil going on in America today—this was a situation where white, Black, Italian, whatever, we all got along.”

Labels of race, ethnicity, background went out the window. “It didn’t make any difference,” Briscoe said.

“There were no problems, no conflicts, no rivalries. Everybody just kind of endorsed each other,” said Sayers. “We interacted on a social level, a professional level, an athletic level. It didn’t matter. We were folks that just enjoyed each other. We were always together, too, between practice, lunch, and studying.”

Tragedy tinged the East Coast-Midwest synergy in 1960 when freshman Darnell Mallory from Summit, N.J., a football and track recruit, died, with 133 others, in the worst recorded aviation accident up to that time.

“Like a lot of fellas that came from the East Coast—he had a real big personality,” Sayers said. “It was Christmas break and everybody was feeling sorry because he didn’t have any money to go home. Everybody kicked in. A dollar here, two dollars there. We finally got enough for him to get a ticket back, and then sure enough he was killed.”

Mallory caught a United Airlines flight out of Eppley Airfield and changed planes at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport. The United Douglas DC-8 flight he was on, bound for Idlewild Airport (now JFK International) in New York City collided midair with a TWA Lockheed L-1049. The planes crashed in separate sites, killing all 128 passengers and crew as well as six persons on the ground.

“It bothered me for years,” Sayers said. “It was one of those things where you’re trying to do a good deed and it just didn’t come out the way it should have.”

The personable Mallory left an impression on his teammates even during the brief time he was with them. Like his Jersey compatriots, he had a bit of wiseguy in him, a trait that helped him and the others quickly adapt to their new environs.

“The fact that they were street savvy didn’t hurt ’em,” Briscoe said. “They got along alright.”

“We thought we were slick and sharp, but we didn’t have anything on those guys,” Curlee Alexander said. “If you weren’t careful, they would beat you out of something. We thought we knew this and knew that, but it wasn’t even close to how they dealt with things.”

The East-Midwest blend offered an education beyond the classroom. “It’s more than just the books,” Alexander said, “You learn a lot about people and life. Those guys came from a different culture. They were quick on their feet. Situations would come up and they would figure it out, and I didn’t have a clue.”

All for One, One for All

Detail of a group photo of 1964 Omaha University football team (detail). Future Hollywood actor John Beasley wears #74. Marlin Briscoe, later to become pro football’s first Black starting quarterback, wears #27, Assistant Coach Don Benning stands to the right of #67. 1965 Tomahawk

The sincerity and openness of the locals, in turn, rubbed off on the newcomers. That, combined with a shared desire to win and push each other to get better, knitted them together. Any cliques around geographic origins were trumped by a common purpose and identity as OU students and athletes.

“Once that common bond took place you couldn’t separate us—we were one,” said Polifrone. “We all hung out together and took care of one another. We’d go to their parties, they’d come to our parties. We developed a rapport with one another that’s still there. The memories are just outstanding. I loved it.”

Alums and boosters served as unofficial host families.

“They took me in and treated me like I was one of their own,” Polifrone said. “I’ll never ever forget it.”

Like his Eastern brothers, he has no regrets coming West. “I thank God I went out there because I grew up and it’s like my second home. I love the people of Omaha. I think they’re great. It’s the best thing that could have happened to me.”

The ties that bind do not break, not even with time.

“We still have relationships to this day,” Sayers said. “Back in 2008 we had a reunion of the fellas. We spent a couple days together, enjoyed each other’s company. You know, you don’t get that unless there is that kind of a relationship that has been developed.”

In 2022 Singleton learned several comrades were unable to contact Marlin Briscoe after they heard he was hospitalized. They worried for his well-being. Sam worried, too, when he couldn’t reach him at first. Finally, they connected.

“Briscoe had just gotten out of the hospital,” Singleton recalled, “and one of the first things he said was, ‘Are you still working on the East Coast-Midwest Project?’ That solidified for me its importance. Here we are with this brotherhood still strong more than half a century later. I said to him, ‘You want to know the real reason why I’m going to do this project?’ He said, ‘Why?’ I told him, ‘Because there are friends of ours who respect you, admire you, love you, and who were worried about you because they couldn’t reach you.’ And he didn’t know what to say, except, ‘Oh Swish, I’m sorry, man.’”

“The project is for the people we have been in relationship with for 55-60 years, and we’re still concerned about each other today. And it’s for all the people the stories in this project can inspire.”

Appreciation runs deep with these East Coast-Midwest veterans.

“I don’t think people would believe the connection we had,” Polifrone said. “All of a sudden, a group of guys come out of nowhere, from Hackensack, Morristown, Union City, Hoboken, Jersey City. We all meet and it’s like a happening. We were all there, we’ve all got the same roots, we stood together, we did our thing, graduated and got our degrees. We made our bones there.”

Omaha was their proving ground and launching pad. “Everything you could need in one place,” Singleton said.

“It was like it was written in stone—this is your future, this is where you’re going. If you’re going to make it, you’ve got to go through Omaha,” Polifrone said.

These once young warriors and adventure-seekers are old now. Some, like Jones and Briscoe, are gone. But the spirit of the surviving brothers is still vital. The value of what they shared still held precious.

“We’re getting up there in age. Some have health issues. We’ve lost a few,” Polifrone said. “I just cherish the years and the fact we were so fortunate we got a direction to head out to Omaha. It was the best move any of us could have made on that chess board.”

“It’s a great story, man,” Briscoe said.

Legacy is a powerful thing, and Singleton is passionate about documenting the legacy of this once in a lifetime experience. He’s seeking support to help fund the research and production of content that tells this true-life human story and the lessons bound up in it. More than ever in this divisive time, he said, audiences are hungry for positive, life-affirming messages that celebrate unity. Omaha lays claim to a unique story of unity Singleton hopes can be a model for young people today in overcoming differences in order to live and work together in harmony.

——————————————————————-

Leo Adam Biga is an Omaha-based author, journalist, and blogger. He is a contributing writer for The Reader, Omaha Magazine, Flatwater Free Press, New Horizons, Afro Swag, and American Theatre. The Omaha native is a 1982 University of Nebraska at Omaha graduate. In 2015 he received an international journalism grant that took him to Uganda and Rwanda, Africa, in the company of world boxing champion Terence “Bud” Crawford of Omaha. Biga’s 2016 book Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film is a compilation of his extensive writing and reporting about the Oscar-winning filmmaker from Omaha. Biga has two new nonfiction books due for release in 2023.

The pipeline largely dried up with the retirement of Don Benning after the 1971 season and the death of Al Caniglia before the start of the 1974 season. There just wasn’t anyone left to sustain it. UNO went on to compete in Division II athletics and eventually dropped football and wrestling en route to competing at the Division I level. To be sure, student-athletes from the East and other parts of the nation still come there, but not in the concentrated way they once did. Singleton hopes that East Coast-Midwest Project will renew this creative and unique pipeline; readers can contact him at [email protected], (804) 246-3276.