“Do you realize I haven’t contributed a dime to this farm today according to the IRS?” Doris Royal told her husband after a twelve-hour day pitching hay and feeding cattle. Starting in 1975, Royal launched a prolonged and ultimately successful campaign to reform federal inheritance tax laws.

The Royal Petition, Doris’s campaign, started from her own kitchen table and became well-known in all fifty states. The petition addressed the issue of estate tax discrimination against married women. The government did not recognize marriage as a true partnership, meaning that after the death of a spouse, estate taxes would apply to property transfer from one spouse to another. Royals did not believe it was fair that she might have to pay estate tax after spending most of her life contributing to the farm’s success.

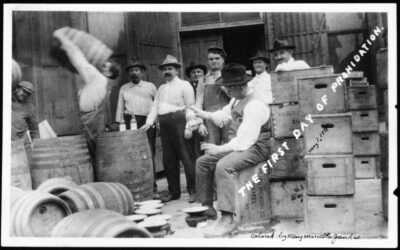

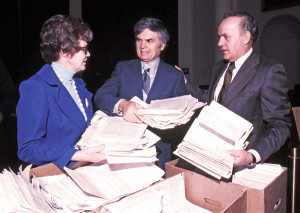

The law she was fighting to change became known as the widow’s tax. She spoke out and gained supporters from a range of political viewpoints, including both conservatives and feminists. Congress and the public became aware of the widow’s tax, but Royal was aggravated by the slow pace of legislation. She requested permission from the Chief Counsel of the House Committee to testify on her topic and made a memorable entrance by walking in with three cardboard apple boxes containing over 130,000 signed petitions.

Six months later Congress finally took action on a bill to modify the estate tax with the Tax Reform Act of 1976. Senator Edward Kennedy’s opposition to the bill persuaded some Democratic senators but failed to prevent Senate approval with bipartisan support and the bill went to President Ford’s desk, where it was promptly signed. The law increased estate tax exemption but did not eliminate the widow’s tax provision.

Royal then began the second phase of her campaign. She and her neighbors mailed letters asking citizens to write to their senators and representatives. Royal even wrote to the newly elected president, Jimmy Carter. The letter campaign and travel meant Royal barely assisted her husband with farm work, but she believed talking at venues was worth her time. A 1980 law fixed some of the problems with the 1976 law, but still did not provide a spousal tax-free of property with 100 percent marital deduction with no exceptions.

Royal’s campaign changed the law on three levels. First, it raised the dollar amount of the estate tax exemptions. Then the government officially acknowledged a woman’s non-working labor contribution as an added value to the estate. Finally, surviving spouses no longer had to pay estate taxes at all. As historian Amy Forss wrote, Royal “did not realize her overall role in changing history while it unfolded thirty years ago, but she did indeed prove that one person can make a difference.”

Read the full Nebraska History Magazine article here (PDF).