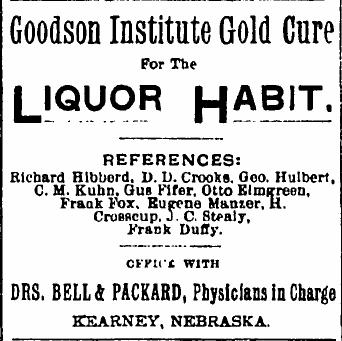

From the Kearney Daily Hub, January 16, 1893 (at left).

From the Kearney Daily Hub, January 16, 1893 (at left).

Nebraska was home during the late nineteenth century to a number of local Keeley hospitals or treatment centers for patients addicted to alcohol, nicotine, and narcotic drugs. Dr. Leslie E. Keeley opened the first Keeley Institute in Dwight, Illinois, in 1879, and by the 1890s every state and nearly every county had a Keeley Institute where injections of “bichloride” or “double chloride” of gold (from which the treatment for alcoholism became known as the “Gold Cure”) could work its wonders for the addicted.

The success of the Keeley institute invited imitation, and it wasn’t long before other treatment centers featuring bichloride of gold were established. Lincoln had its own institute for the cure of alcoholics and morphine addicts, organized by Dr. M. H. Garten. Dr. Garten enjoyed some success outside Lincoln. Seward had a Garten Institute in 1892 headed by Dr. J. H. Woodward, and Sacramento County, California, had a Garten Gold Cure Institute Company in 1894. Dr. M. D. Bedal’s Gold Cure Company of Blair guaranteed a “perfect and permanent cure” for addictions, according to the Omaha Daily Bee of November 15, 1891. During the early 1890s Kearney newspapers carried advertisements for the Goodson Institute in Kearney (which promoted its “Gold Cure for the Liquor Habit”) and the Grand Island Bi-Chloride of Gold Institute.

The ideas of Dr. Keeley and his imitators were reflected in this campaign button praising William Jennings Bryan, with his free-silver ideology, as the “American Gold Cure.” NSHS 4610-21 (at right).

Despite its widespread popularity and the testimonials of patients, many suspected the bichloride of gold practitioners of being quacks. The Kearney Daily Hub on August 10, 1893, even reported tongue-in-cheek a new use for bichloride of gold in “salting” gold mines:

“The plan, as near as has been found out, is to take a solution of Dr. Keeley’s bichloride of gold and with a hypodermic syringe inject it into the walls or bottom of the mine it is desired to ‘salt.’ The rock being porous absorbs the liquid readily and leaves no trace of anything except the glittering gold. . . . . The writer heard of one case last week where $10,000 cash was paid for a mine that had been given ‘the jag cure’ and was not worth five cents.”

By the time of Keeley’s death in 1900, however, an estimated 400,000 patients had taken the Keeley cure. The institute in Dwight closed in 1966.

– Patricia C. Gaster, Assistant Editor/Publications