A portrait of Mrs. Grace C. Richardson

By Breanna Fanta, Editorial Assistant

Scrapbooks often hold sentimental value, but for historians like Amy Helene Forss, they can serve as primary sources by providing key perspectives of historic value. As Forss examined the pages of four scrapbooks compiled by Nebraska suffragist Grace Crandall Richardson, she wanted to learn more about her. Forss details her discoveries in “Grace Crandall Richardson: Nebraska’s Persistent Suffragist,” in the Nebraska History Magazine’s Winter 2020 issue.

In the 1910s Richardson chaired the Omaha district of the Nebraska Women’s Suffrage Association, helping coordinate events. She helped supervise the group’s 1914 ballot initiative petition drive alongside two other women: board member Katherine Sumney and NWSA president Mrs. Draper Smith. Together they became known as “The Big Three.”

The 1914 ballot initiative sought to amend the state’s constitution to allow women to vote. It would do so by gathering enough signatures to place the measure on the November ballot in hopes that a majority of Nebraska voters would approve it. With 48,035 signatures, NWSA’s petition was the largest application filed in Nebraska at the time.

To build support, Richardson contacted prominent women in various Nebraska communities to ensure the presence of more local leaders at rallies.

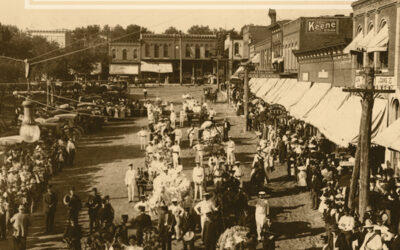

One of the biggest events was a suffrage parade in Blair on July 11. Reluctant to make speeches, Richardson circulated among the large crowd, handing out suffrage literature, talking with people, and giving short speeches to small groups. She viewed herself as “shy by nature.” Her husband described her voice as “an ingrowing whisper.” Some people questioned whether it was right for a married woman and mother to spend so much time campaigning, but Richardson said her work was a “full-time family affair,” pointing to her husband and son who were both present at the parade.

Despite their efforts, Nebraska voters rejected the proposed women’s suffrage amendment. It lost by a 5 percent margin.

Looking at the demographics, however, the suffragists soon found a solution to that 5 percent when the state legislature considered a women’s suffrage bill.

During World War I, people became suspicious of German-Americans. The Nebraska legislature considered repealing the Mockett Law, which allowed schools to teach foreign languages—such as German. Pro-suffrage legislators agreed to oppose the Mockett repeal. In exchange, German-American legislators, who had previously opposed women’s suffrage, now agreed to vote for it. As a result, on April 21, 1917, legislature passed a bill allowing Nebraska women limited voting rights.

In response, anti-suffragists circulated a referendum petition to repeal the suffrage law. They gathered 30,000 signatures in only three months. That placed the repeal referendum on the ballot. After the measure passed, Nebraska women’s new voting rights were suspended.

Suspicious of the sudden signatures, the NWSA asked Secretary of State, Charles Pool, to see the petition to investigate. Pool refused, claiming they would need to purchase a copy.

Examining thousands of signatures, Richardson created an alphabetical card catalogue of the 18,000 Douglas County petition signatures to efficiently compare these to the list of registered voters. Full pages of forged signatures were discovered written in the same handwriting and names of men who died years prior. These fraudulent signatures not only invalidated the petition, but the vote as well. NSWA took this evidence to court: Barkley vs Pool. It was “the case against the strongest machine of the state,” according to Richardson.

Nebraska’s Supreme Court ruled in favor the suffragists and Richardson was praised for her timely and effective work within the investigation. Following this, the anti-suffragists were ordered to pay all legal costs, petition requirements were mandated, and the NWSA was refunded $1,200.

In August of 1919, Nebraska became the 14th state to ratify the 19th amendment and finally Nebraska women were granted the right to vote in elections at the local, state, and presidential levels. “The Big Three” were the first female registered voters at the Omaha City Hall and the following year earned NAWSA Honor Roll Certificates.

In 1950, G.C. Richardson donated her scrapbooks, detailing the Nebraska suffrage events and activities, to History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society) in celebration of the 30th anniversary of the 19th amendment.

She passed away January 9, 1963.

Today, those four scrapbooks remain at History Nebraska and pay homage to the state’s suffrage movement and to Nebraska’s “persistent suffragist,” Grace Crandall Richardson. Her role in the movement not only helped the cause, but also represented who she was as a person.

The Richardson family’s vehicle, July 11th, 1914, at the suffrage parade in Blair.

A page from one of Richardson’s suffrage scrapbooks featuring “The Big Three”: Richardson, Katharine Sumney, and Mrs. Draper Smith.

(originally posted 11-27-2020)

The entire article can be found in the Winter 2020 edition of the Nebraska History Magazine. Members receive four issues per year.