“The Chimney is rough and looks as if it would not stand a week,” wrote Franklin Starr in 1849.

By David L. Bristow, Editor

“The Chimney is rough and looks as if it would not stand a week,” wrote Franklin Starr in 1849. Starr was one of hundreds of thousands of emigrants who passed Nebraska’s most famous landmark on his journey. More travelers wrote about Chimney Rock than any other landmark along the Oregon, California, and Mormon trails.

While traveler called Chimney Rock “the most remarkable thing I ever saw” and “a wonderful display of the eccentricity of Nature,” many people didn’t think it would be around much longer.

“It is fast mouldering to ruins and if you don’t look sharp, my friends, you will never see it,” wrote John Wood in 1850.

Chimney Rock was millions of years in the making. About 38 million years ago, streams and wind started carrying silt and sand from the Rocky Mountains to the Nebraska Panhandle. This material built up into layers of clay that are visible in the Rock and surrounding buttes. Erosion slowly carved out the North Platte Valley and sculpted Chimney Rock into its unusual shape.

So, yes, the “Rock” is mostly clay. This surprised some emigrants. “It is called rock, but it is nothing but sand and dirt,” wrote Alonson Sponsler in 1850. Sponsler didn’t know it, but it is also accurate—and more awe-inspiring—to say that Chimney Rock is made of bits of the Rocky Mountains, and that it contains a good deal of volcanic ash besides. Ancient volcanoes in Western Colorado erupted over millions of years, mixing ash with the clay. Particularly violent eruptions created two lighter-colored bands of ash that are visible in the rock’s base and spire.

About five million years ago, the North Platte Valley started to erode faster than it was built up. So why didn’t Chimney Rock erode away too? It might be the hard cap of sandstone protecting the spire. Prominent buttes such as Scotts Bluff are similarly protected. Even so, wind and water continue to wear the spire away.

Erosion isn’t the only thing that affects Chimney Rock’s shape. Pieces have also been broken off by lightning strikes. And at least since the 1860s rumors have circulated that soldiers used to fire cannons at the Rock for target practice—but that seems to be just a story.

A newly expanded visitor’s center with new exhibits is open at Chimney Rock National Historic Site. Include it in your travel plans when you visit western Nebraska state parks this summer.

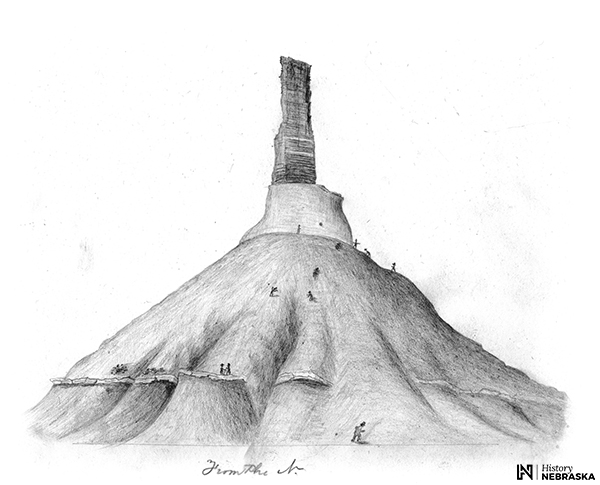

Top of page: A bird’s-eye view highlights the Rock’s layers and sharp angles. How long would it take to carve this using nothing but water and wind? History Nebraska RG3319-PH1-44

Below: Views of a changing Chimney Rock.

Artist William Quesenbury drew Chimney Rock in 1851, looking southwest from near present-day Highway 92. History Nebraska 8783-5

The exact shape of Chimney Rock depends on where you are standing, and shadows vary with the season and time of day. Still, the spire is definitely more pointed in this early 1900s view from the east. Oregon Trail pioneer and re-enactor Ezra Meeker stands in the foreground. History Nebraska RG959-5-1

Here’s a similar view from a mid-twentieth century postcard. Does the point look shorter to you? History Nebraska RG2273-5-10

And here’s a present-day view from the same direction, which today is the site of the Chimney Rock visitor center. How long do you think the Rock will last? Photo by Josh Lottman, History Nebraska