Most Nebraska teachers were paid poverty wages in the early 1920s, even before an economic recession prompted school districts to slash budgets even further.

By David L. Bristow, Editor

Most Nebraska teachers were paid poverty wages in the early 1920s, even before an economic recession prompted school districts to slash budgets even further. In 1922 a statewide publication called The Nebraska Teacher calculated how much money teachers actually needed. The result wasn’t necessarily what taxpayers and school boards wanted to hear.

“The salaries of teachers absorb about two-thirds of the school budget in most schools,” wrote A.L. Caviness, president of the State Teachers’ College in Peru (today’s Peru State College). “To reduce taxation, therefore, the first thought is to cut salaries and the result is obtained.”

Then as now, Nebraskans complained about their property taxes.

Caviness suggested that each district put together a “representative committee, including a member of the school board, a business man, a professional man, a mother of a family, a club woman, a teacher and a heavy taxpayer” (i.e., a wealthy citizen) to calculate:

- Cost of room for 12 months

- Cost of meals for 12 months

- Cost of laundry for 12 months

- Allowance for doctor, dentist, etc.

- Allowance for clothing for 12 months

- Allowance for church, charity, etc.

- Allowance for investment or saving

Was Caviness suggesting that salaries be cut to that level? Consider another article in the same issue. Here’s what G. H. Lake, school superintendent at Orleans, came up with:

The lines left blank for lack of extra money are the main point.

“If such a teacher is to make any investments, or to save money for a rainy day,” Lake wrote, “it is clear that she can do so on her present salary only at the expense of her own further self-improvements.”

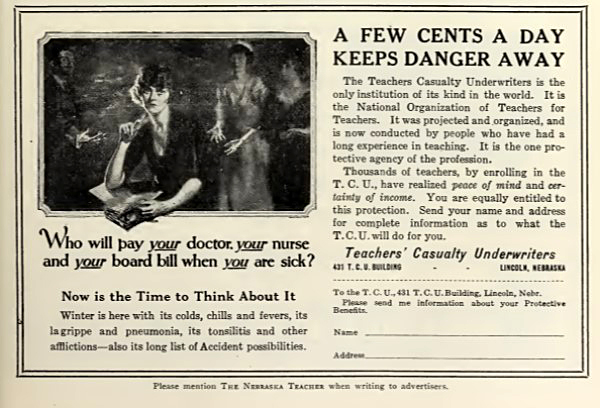

Notice that one of the blank lines is for insurance. Teachers weren’t paid sick leave or provided with health insurance. They had to buy their own, if they could afford it. A typical Orleans teacher could not.

Health insurance ad from The Nebraska Teacher, December 1921.

Salaries were set by individual districts. The Fairbury superintendent wrote that “normal” graduates were paid $1,000 to $1,400 a year; those with a bachelor’s degree earned $1,200 to $1,700. (Teachers’ colleges were called “normal schools” and offered diplomas roughly equivalent to a modern associate’s degree.)

Rural districts paid less, and as a result many rural teachers were barely educated themselves. Mari Sandoz was seventeen when she passed her eighth-grade examination in 1913 (she’d missed a lot of school; not unusual for the time). Without telling her domineering father, she soon saddled up a horse and rode eighteen miles to Rushville to take the rural teacher’s examination. She became a rural schoolteacher when she was still a year under Nebraska’s legal age for teaching. “That was not unusual on the frontier,” writes Sandoz’ biographer, Helen Stauffer.

In September 1921, The Nebraska Teacher condemned the underfunding of rural schools, complaining that nationally, half of all schools “have less than $1000 a year to spend for all purposes.” In York County, Nebraska—a relatively prosperous county—70 of the county’s 103 schools spent less than $1,000 a year for all expenses.

Such schools, The Nebraska Teacher argued, did not adequately educate their students. In Buffalo County, “not one of the poor counties of the state,” 80 of the county’s 118 schools operated for less than $750 a year. “Two schools in the county did not graduate a single pupil from the eighth grade in eight years. The median number of [eighth grade] graduates from all the rural schools in this county for 8 years was 1.06 pupils.”

Rather than reduce teacher salaries, The Nebraska Teacher argued that both rural and urban communities needed to spend more. “The purpose of the public schools is to train boys and girls so that they may be become helpful and efficient citizens in their communities,” wrote J. H. Beveridge, superintendent of Omaha schools.

Beveridge acknowledged that “it is difficult to measure the value of a school in dollars and cents,” but he didn’t question whether or not it was appropriate to make dollars and cents the universal measure of value. Perhaps he knew his audience. He titled his article “Public Schools as an Investment.”

“If the public schools were taken out of your city your real estate would be almost without value,” he wrote, arguing that good schools boosted earnings, commerce, and property values.

“You are a stockholder in the public schools,” he said.

As for the teachers themselves, The Nebraska Teacher didn’t make a business argument so much as a humane and patriotic one. “Teachers are human and must live,” A. L. Caviness wrote, “but their patriotism and loyalty is on a par at least with the most devoted of public servants.”

(originally posted 3/30/2021)

Sources:

J. H. Beveridge, “Public Schools an Investment, The Nebraska Teacher (January 1922), 178-79.

A. L. Caviness, “Determining Salaries Sensibly,” The Nebraska Teacher (January 1922), 177.

G. H. Lake, “Cost of Living Balance Sheet,” The Nebraska Teacher (January 1922), 178.

George L. Towne, “Can Adequate Financial Support Be Secured for Rural Schools?” The Nebraska Teacher (September 1921), 18-20.

(Several volumes of The Nebraska Teacher are archived at The Internet Archive [archive.org] and Google Books [books.google.com].

Helen Winter Stauffer, Mari Sandoz: Story Catcher of the Plains (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982), 36-37.