F. W. Carlin survived a 143-foot fall down a well, but then he had another problem. Nobody knew he was there, and no one was likely to coming looking for him. If was to make it out alive, he would have to do it on his own.

F. W. Carlin survived a 143-foot fall down a well, but then he had another problem. Nobody knew he was there, and no one was likely to coming looking for him. If was to make it out alive, he would have to do it on his own.

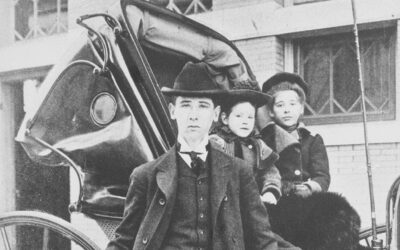

The photo above shows the digging of a different Custer County well. Well digging was a vital, difficult, and dangerous task on the high plains. Shallow wells could be dug with an auger, but on tablelands a well might have to go down 100 or even 200 feet. Before hydraulic drilling, sometimes the only way to do it was to go down the hole yourself and have a man to raise and lower the rope.

Professional well-diggers learned their trade by experience. It wasn’t just the digging. Sections of a well might also need to be “curbed” with wooden boards to keep them from caving in. There were a lot of ways to die: cave-ins, falling buckets, or asphyxiation from “the damp” (carbon monoxide).

Abandoned wells could be dangerous too, as Mr. Carlin discovered in 1895. Did he make it out? Here’s the full story, as told by historian Everett Dick in Conquering the Great American Desert, published by the Nebraska State Historical Society (aka History Nebraska) in 1975:

“The danger from these deep wells was not confined to well diggers and those who went down to repair curb or water-raising equipment. After the great exodus of settlers from western Nebraska in the 1890’s, vast expanses of the country lay unoccupied. Many homesteaders had either abandoned their claims, allowing them to revert to the government, or had mortgaged them to Eastern loan companies which left their Nebraska property unoccupied. This meant hundreds of old, deteriorating wells remains on these abandoned claims—an invitation to disaster to someone who might by chance fall in one. The best-known instance of such an accident was that of F. W. Carlin, which is widely known in Nebraska history. While Carlin was on business fifteen miles north of Broken Bow late in the evening, he inadvertently took the wrong road, which led to some old sod buildings. When one of his horses stopped, Carlin got out of the buggy and walked along beside it to see what was the matter. In the twilight he stepped into one of these unused wells.

“A well man himself, Carlin immediately realized his predicament. Placing his feet together, he uttered a prayer: ‘Oh God have mercy on my soul!’ When he struck the water 143 feet below, he was stunned, a rib broken, and an ankle painfully sprained, but the water was only chest deep. On examination he found that it was a square well curbed with wood; and by sheer nerve, indomitable will, and ingenuity, he was able to whittle footholds with a pocket knife and otherwise devise means of scaling the difficult walls. After two days and nights of effort, he reached the top where he grasped some large sunflower stalks, pulled himself out, and lay exhausted on the ground for a time. Then he knelt and thanked God for his deliverance. With a sprained ankle and a broken rib, he could not walk, but crawled painfully toward the only house in the whole country, a mile and a half distant. Famished, he pulled seed pods off wild rose plants along the road and ate the red meat as he inched his way along to the house, where he found help.” (p. 106)

Professor Dick says that the incident prompted the state legislature to pass a law requiring owners of abandoned land to find these wells and fill them. Not only did this remove a hazard, but it also provided employment for the poverty-stricken settlers who remained.

(Photo: “Mr. Moyer digging a well in east Custer County, Nebraska,” by Solomon D. Butcher, 1886. History Nebraska RG 2608-0-2207-a)

(Posted 7/28/2020)