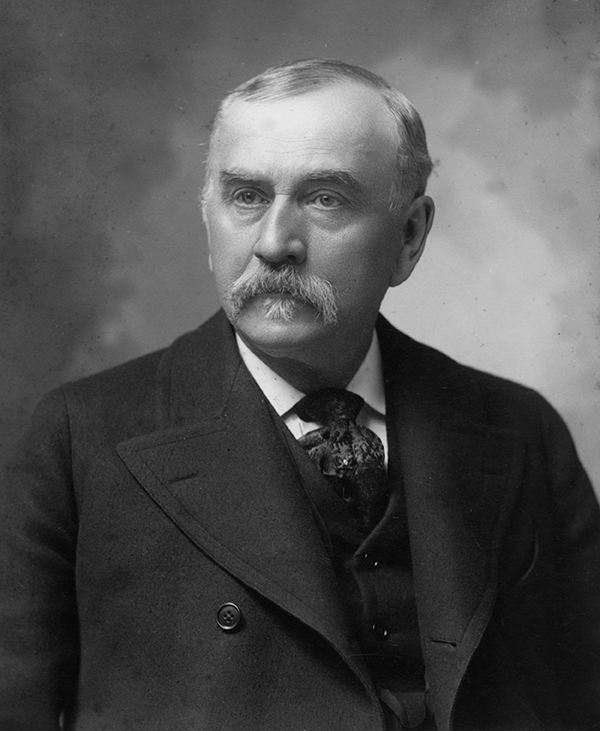

As you prepare to take down your tree after the holidays, here’s Nebraska Hall-of-Famer J. Sterling Morton with a cup of holiday cheer for you. Morton (1832-1902) is usually remembered as the founder of Arbor Day and the builder of Arbor Lodge in Nebraska City. Most Nebraskans have forgotten that he was also both one of the most distinguished and despised of Nebraska’s early politicians.

As you prepare to take down your tree after the holidays, here’s Nebraska Hall-of-Famer J. Sterling Morton with a cup of holiday cheer for you. Morton (1832-1902) is usually remembered as the founder of Arbor Day and the builder of Arbor Lodge in Nebraska City. Most Nebraskans have forgotten that he was also both one of the most distinguished and despised of Nebraska’s early politicians.

Morton served twice in the territorial legislature, as territorial secretary from 1858 to 1861, and on two occasions as acting territorial governor. He also served as secretary of the U.S. Department of Agriculture in the Democratic administration of President Grover Cleveland from 1893 to 1897.

Morton was also an ardent defender of slavery and a fierce critic of Abraham Lincoln, whom he considered a tyrant leading “the country to eternal war or eternal disunion.” Prone to bombast, and suspected of disloyalty during the Civil War, Morton so infuriated his opponents that the Nebraska Herald (Plattsmouth) once claimed that even Cass County Democrats despised Morton as “the man who would sacrifice their interests, the Nation, and, if necessary, his grandmother, for his own political ends.”

Nevertheless, Morton remained at the head of the Nebraska Democratic Party until William Jennings Bryan and the Populist movement overtook him in the 1890s.

Morton’s chief legacy, however, is his promotion of tree planting on the prairies. Upon his initiative, the State Board of Agriculture in 1872 established Arbor Day. On November 23, 1899, Morton used his Nebraska City newspaper, The Conservative, to attack the custom of cutting down healthy trees for use as holiday decorations. He wrote:

“Millions upon millions of the straightest, most symmetrical and vigorous hemlocks, spruces, pines and balsams, will soon be aboard freight cars and going towards cities to be put into homes for Christmas trees, which shall bear tin bells, dolls, bon bons, glass bulbs and all sorts of jimcracks for the amusement of children. The generations following will want for lumber which these Christmas trees would have made.”

One can imagine the reaction to such holiday heresy. Even today, the headlines practically write themselves. (Alternate headline for this article: “Bah! Humbug! J. Sterling Morton Denounced Christmas Trees but was OK with Slavery.”)

One can imagine the reaction to such holiday heresy. Even today, the headlines practically write themselves. (Alternate headline for this article: “Bah! Humbug! J. Sterling Morton Denounced Christmas Trees but was OK with Slavery.”)

Surprisingly, press response was mild, even approving. The Courier (Lincoln) on December 9, 1899, agreed with Morton, saying, “The fragrant fir hung with presents, glittering with lights, and surrounded by the beautiful, happy faces of children is a pleasant sight. But it costs the life of a tree and we cannot afford it.” The Kearney Daily Hub said on December 13: “There are a great many of us . . . . who have not stopped to think about it at all . . . and it seems now that attention has been called to the wanton destruction aforesaid, that it ought to be stopped. But he [Morton] shouldn’t deprive us of our Christmas trees without offering us something else.”

Why all the Christmas tree guilt? It’s hard to imagine today just how few trees Nebraska had in the early decades of its settlement. Indigenous peoples had long used fire to manage the prairies as bison habitat. Settlers from the wooded East found Nebraska’s openness inconvenient and frankly disturbing. And people who spent decades encouraging tree planting couldn’t help but recoil at what they saw as the wasteful and inappropriate cutting of trees. They even thought Nebraska would someday produce its own lumber, though they apparently didn’t anticipate Christmas tree farms or artificial trees.

Nor did anyone else. But the Germanic tradition of Christmas trees was too well established in America by the late nineteenth century for Morton or any other newspaper editor to talk people out of it, whether they lived on the Nebraska prairie or not.

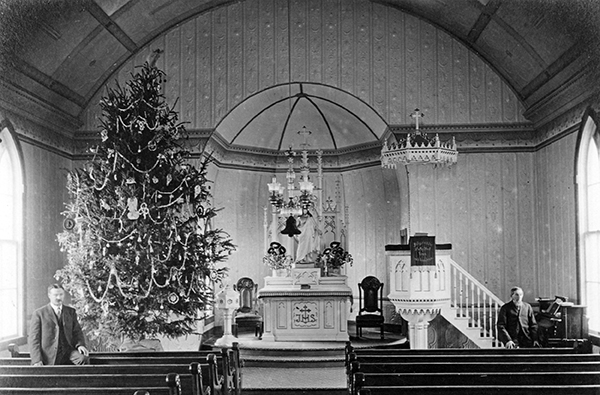

Photos: Top and bottom: Trinity (German) Lutheran Church, Talmage, Nebraska, late nineteenth century. The men are unidentified. NSHS RG2352-8-3.

Center portrait: J. Sterling Morton in 1897. He will tolerate your holiday jimcracks and bonbons as long as you don’t cut down a tree on which to hang them. NSHS RG1013-3-1-1