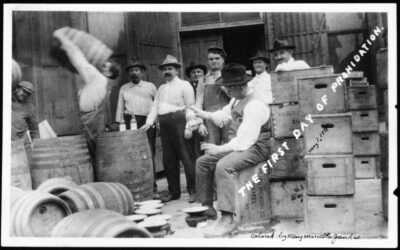

Fig. 1: A group of Displaced Persons gather for a commemorative ceremony in Lincoln, 1950s. Jakob Drozdow is second from right. Unless otherwise noted, photos in this article are from the records of the Nebraska Committee on the Resettlement of Displaced Persons, History Nebraska, RG1: SG33

This is the first of three-part series. The entire article appears in the Fall 2023 issue of Nebraska History Magazine. You can receive four issues a year of Nebraska History Magazine with a Household-Plus membership. Learn more here.

By William Kelly

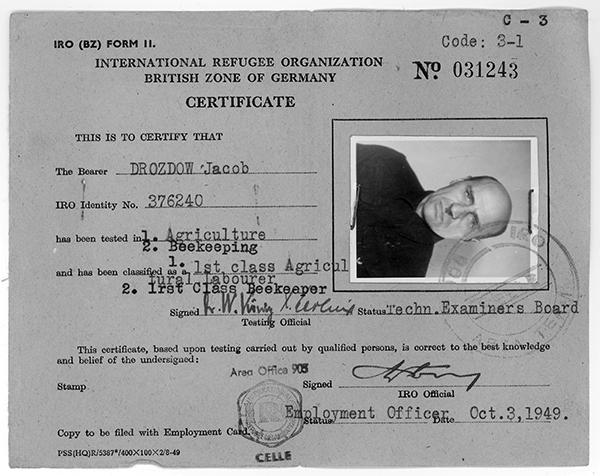

Jakob Drozdow was all alone when he arrived in New York City in August 1951. The 54-year-old had no family and only a limited grasp of English. Before World War II, Drozdow worked in apiary and agriculture in Russia. But the war disrupted his life and the lives of millions of other Eastern Europeans. Fearful of either Nazi aggression or Soviet persecution, these displaced persons searched for security away from their homelands. Like many other displaced men, women, and children, Drozdow weaved his way through postwar Allied refugee camps in Eastern and Western Europe until he embarked on a transatlantic voyage to the United States. From New York City, Drozdow arrived in Nebraska where an entirely foreign language and foreign culture compounded a challenging immigrant experience.

The experiences of Jakob Drozdow and those of thousands of other displaced persons who resettled in the United States after World War II is a generally understudied feature of postwar history. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, a hierarchy of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), national governments, and religious organizations relocated “displaced persons” from mostly Eastern European countries to Western Europe, Australia, Israel, and eventually the United States. In postwar Nebraska, as in other states, the governor initiated the Committee on Resettlement of Displaced Persons. Board members included leaders of dominant religious groups in the state who worked to find sponsors for displaced persons. A similar organizational structure persists to this day.

Nebraska’s resettlement committee paired displaced persons with sponsors across the state. The Russian-born Jakob Drozdow, an experienced apiarist and agricultural laborer, first found agricultural work with a farming family in Burchard, Nebraska. Later, Drozdow relocated to Lincoln and labored in the city’s coal industry until his death. Other immigrants were paired with other Nebraska sponsors across the state from Enders to Omaha, Hay Springs to Springview, Lincoln to Holdrege. Their stories survive in the archive at History Nebraska.

This article places Nebraska’s involvement in the resettlement of displaced persons after World War II in the broader national context. While thousands of displaced persons arrived in the United States on the East Coast, not all of them stayed there. Nebraska offered jobs and education in rural and urban settings. The organizational apparatus in place—between government and religious organizations—was effective not only in relocating displaced persons, but also in shepherding them through their cultural transition in postwar America.

Immigrants have relocated to all parts of Nebraska since statehood was granted in 1867 and continue to do so today. History Nebraska’s archival collection from the Nebraska Committee on the Resettlement of Displaced Persons helps us learn from one chapter of immigration in and around Nebraska that few have touched on before. Through this research, we will gain a better understanding of one episode in a longer series of immigration to and through Nebraska.

After eight years of living and working in Nebraska, Jakob Drozdow passed away in Lincoln on September 23, 1959. He was buried in the city a few days later. Drozdow’s obituaries were lean, offering little information about his surviving family and friends. One can suspect that other displaced persons had similar postmortem write-ups. Indeed, from his initial arrangements in southeastern Nebraska to his final years working in Lincoln’s coal industry, we still have much to learn about Drozdow’s life, his work, his struggles, and his successes. And, as this project will show, the life of Jakob Drozdow illustrates a much larger trend of displaced persons’ strength in the face of adversity upon relocating to Nebraska.

Fig. 2: In 1949, Jakob Drozdow was certified by the IRO as adept in agricultural labor and beekeeping.

About the author: William Kelly is a PhD candidate at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Department of History. Kelly completed this project as a graduate research assistant at History Nebraska; the UNL history department provides an assistantship in which a doctoral student conducts research under the supervision of Nebraska History Magazine’s editor.