By Joy Carey, Editorial Assistant

February 19, 2015 (updated March 21, 2022)

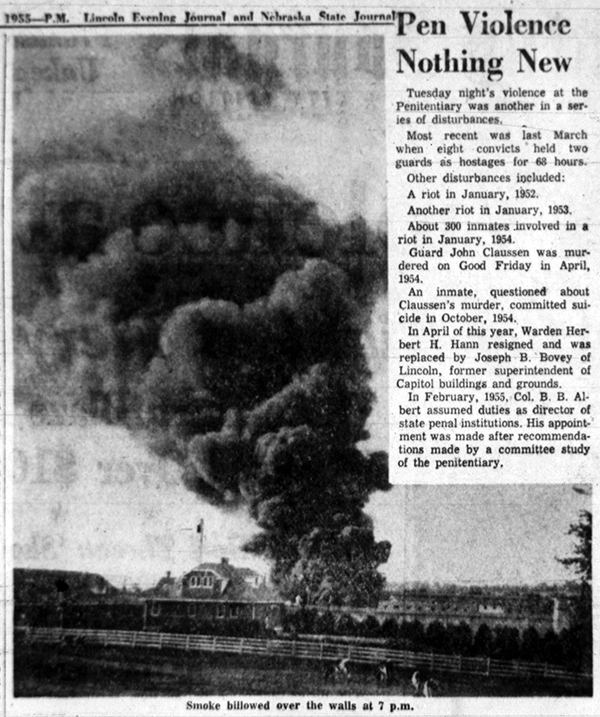

The prisoners called it a protest. The guards called it a riot. But on August 16, 1955, fires blazed and smoke billowed out of the Nebraska State Penitentiary…and the inmates’ activism could be called anything but quiet.

In the Spring 2015 issue of Nebraska History, Brian Sarnacki writes about the incident and the circumstances that led Nebraska inmates to violently demand prison reform.

In January of 1955, the Nebraska prison system was already under some review. Riots in 1954 had led to an investigative committee, and the Board of Control hired prison expert Sanford Bates to examine Nebraska prisons.

Bates’s review was less than stellar. He criticized the State Penitentiary’s poorly-educated guards and lack of purpose, as well as some of its punishment practices.

Bates had particular criticism for “the hole,” which was a section of concrete cells used to punish troublesome prisoners. Inmates assigned to the hole got a slab of concrete to sleep on, barely any light, and little more than bread to eat.

In his memoir, former inmate Ray “Ramon” Tapia described the Nebraska State Penitentiary as “a bleak and miserable place to live.” Tapia remembered being sentenced to the hole indefinitely for minor infractions, or as pressure to confess to breaking the rules.

The prisoners told the investigators that the warden, deputy warden, and certain guards were abusive. They protested the lack of sufficient medical attention and reading materials. Despite Bates’s report, political attempts at prison reform continually stalled or fell short. Lacking much of a public voice, some prisoners saw violence as the only way to get attention for their complaints. Ninety-four inmates signed a letter to the Omaha World-Herald, warning, “When a sleeping dog gets kicked just so long he will eventually get up and bite, and it’s in the biting stage as far as we convicts are concerned as we had the share of kicking.”

On March 27, 1955, one prisoner, John Ward, broke out of his cell using a spoon and took prison guard Warren Miller as a hostage. Soon, a group of twelve prisoners had control of the three-story jail building, which stood separately from the rest of the complex. The inmates had captured one small structure, but more importantly they had captured the attention of the public, the media, and the governor.

Lincoln Journal, Aug. 17, 1955

Nebraska Governor Victor Anderson promised to meet with the rebels personally to hear their grievances, if they let the guards go safely. It was a momentary victory for the inmates. However, the only change resulting from the meetings was the replacement of the warden. The new warden was inexperienced, and inmates feared that he would not be able to monitor abusive guards. The prison administration and guards found ways to retaliate against the inmates for making a stir.

The months of conflict boiled over into the August fire-settings: a 13-hour uprising by more than 200 convicts that resulted in more than $100,000 worth of damage.

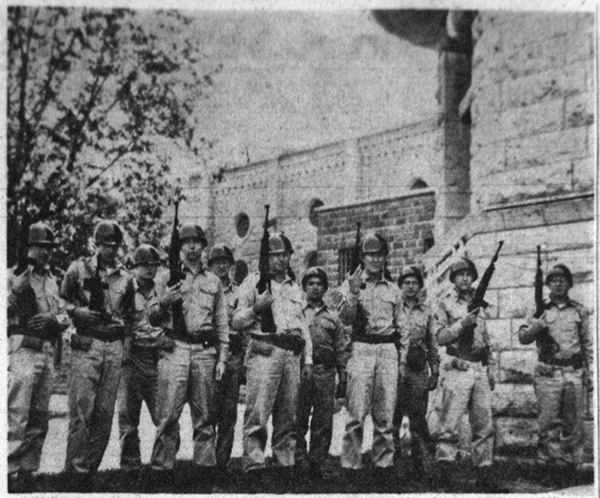

Lincoln Journal, Aug. 20, 1955

Public opinion quickly hardened towards the prisoners, embracing “get tough” discipline policy. Nevertheless, Sarnacki writes:

“Public pressure to end the violence shows the inmates’ success in violently pushing their demands whenever officials attempted to quiet discussion on penal reform. The inmates began 1955 by demanding the removal of the prison’s top administrators, and before the end of the year the governor appointed a new Board of Control chairman and warden, though the qualifications of each were questionable. In addition, the Board of Control created a new position to oversee the prison system, and hired an experienced penal administrator to fill it. In 1956, a new, larger maximum security building opened, replacing the outdated jail and its nineteenth-century furnishings.”

Read more in Brian Sarnaki’s complete article (PDF) from the Spring 2015 issue of Nebraska History Magazine.