July 20, 2019 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the first moon landing. Here at History Nebraska, we’ve looked through some of our microfilmed newspapers to see what Nebraskans thought about it at the time.

By David L. Bristow, Editor

July 20, 2019 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the first moon landing. Here at History Nebraska, we’ve looked through some of our microfilmed newspapers to see what Nebraskans thought about it at the time.

The Omaha World-Herald reported surprisingly little reaction on launch day, July 16. “In one downtown restaurant-bar, only 10 persons moved from counter or dining tables to view the TV set tuned to the liftoff.” The bartender thought this was a sign of confidence. He said, “We’ve had so much success everybody seems to feel there’s no sweat over this one.”

But everyone was glued to their TV when the Eagle landed on Sunday, July 20. Even Boys Town let the boys stay up past bedtime, and many people took off work Monday to watch the lunar blast-off for the homeward flight.

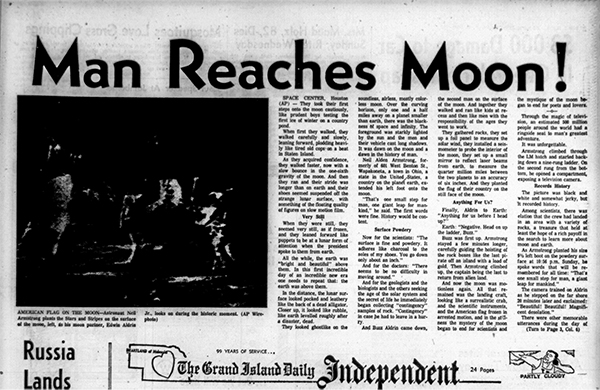

Like people everywhere, many Nebraskans found the experience beyond their powers of description.

“It would probably take a week of thought to express adequately what one feels about it,” Ralston attorney Joseph J. Vance told the World-Herald.

“Events defied eloquence,” said the Scottsbluff Star-Herald, as men “walked on the moon while most of the whole family of man watched in ‘real time.’”

The worldwide TV broadcast was nearly as much of a technological marvel as the flight itself.

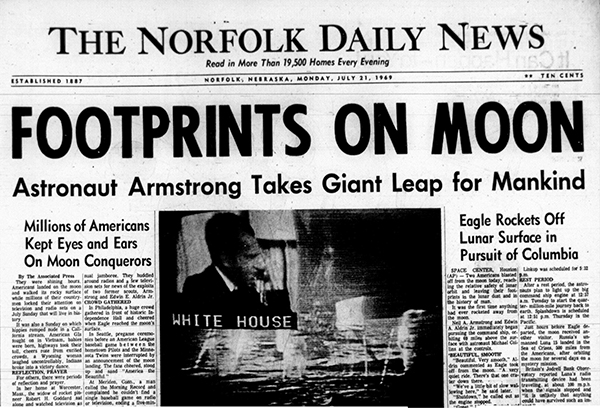

“It was sensational, really amazing how beautiful the pictures appeared from the telecasts,” Mayor Ed Vrzal told the Norfolk Daily News. “It looks as if nothing is impossible now.”

Many people expressed feelings of patriotism. “The proudest moment for me was seeing our flag on the moon,” said 17-year-old Marlene Alben, a student attending summer classes at Omaha Central High School.

Older Nebraskans often spoke of technological change. On launch day, the Kearney Hub reported that “George Munro, long-time Kearney attorney and World War I aircraft pilot, remarked that ‘there is quite a difference between the old wrecks we thought were wonderful with their baling wire, and the machinery of today.’”

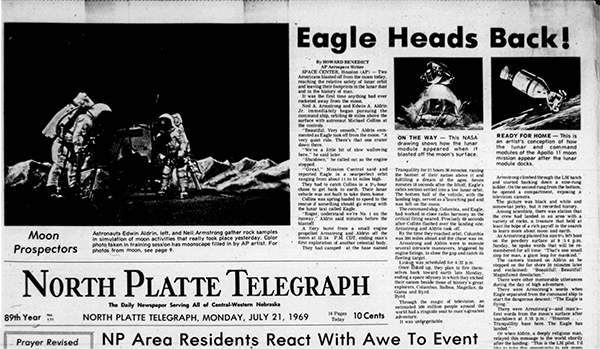

After the moon landing, the North Platte Telegraph commented that rancher Byron Sellers Sr. of Wellfleet “was pretty ‘far-out’ in 1918 when he purchased one of Lincoln County’s first Model T Fords.” In 1916 Sellers and his new bride rode away from the church in a horse and buggy. “To see such an advancement in a lifetime is overwhelming,” he said.

“It makes you sit down and wonder what will be happening in the next generation and what effect it will have on their lives,” Washington County Clerk Lucille Poulson of Blair told the World-Herald.

Attorney Wade Stevens of McCook had been a flight instructor during World War I. “Stevens was doubtful about spending the billions of dollars needed to reach the moon,” the World-Herald said. “But he said the knowledge gained could eventually mean travel to other planets.”

Father Floyd Wessling of Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Norfolk believed the resulting scientific advancement would help the world’s underdeveloped countries, and that the “United States will try to develop the moon as much as possible, before moving the quest to other planets.”

But many people expressed ambivalence. “It’s a terrific chance they’re taking,” said Mrs. Michael Milobar, an Omaha housewife. “If they help the world I’m for them, but right now I’m not sure we belong up there. I feel for the fellows.”

Rev. Martin Gruenke, assistant pastor of Zion Lutheran Church in Kearney, told the Kearney Hub that the landing was “one of man’s greatest feats of the century and I praise God for it,” but added that the nation should “rechannel some of our efforts to the physical and spiritual needs here.”

Serving the local African American community, the weekly Omaha Star’s only coverage of the moon landing was a report on the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s “Moon-Hunger Protest” in Charleston, South Carolina. Dr. Ralph Abernathy and Hosea Williams had been jailed during the Charleston Hospital Workers’ strike. The men said their two-week fast was a protest not against space flight, but against the government’s unwillingness to “tackle the job of eliminating poverty with the same degree of zeal that they have utilized in assuring America the position of being first in the space race.”

Underlying many Nebraskans’ comments was a recognition that the country was deeply divided and that the world was a profoundly troubled place. The moon landing prompted a mixture of awe, reverence, and hope that somehow this stunning event promised better times to come.

“I hope it does something for the future, not only for peace on earth but throughout the universe,” said Edward Slater, an Omaha restaurant cashier.

A.P. Dahl of York echoed this thought as he told the Kearney Hub about his World War I job of overhauling “Roarin’ 90s,” the 90-horsepower motors on training planes. “Who knows,” he said, “maybe those astronauts will find something that will make peace possible in this world. We can’t stand still.”

What would the future bring? “In the year 2525,” sang Lincoln duo Zager & Evans in the reigning US number-one hit single, “if man is still alive, if woman can survive…”—if.

The Scottsbluff Star-Herald hoped that “the awe and admiration that were so fully apparent Sunday will become permanent additions to man’s religious instinct. We hope that man will be able to hold onto that feeling of being part of the human family. We hope that man will take heart from the accomplishment of the ‘impossible’ and zero in on other impossible tasks such as conquest of cancer, elimination of poverty, and abolition of war.”

In similar ways, many newspaper editorials combined religious and technological references, and reporters sought comment disproportionately from clergy and old pilots. It’s curious, too, the way the Nebraska press echoed hippie themes of peace and brotherhood.

“Come on people now,” sang the Youngbloods in a top-five hit that summer, “smile on your brother, everybody get together, try to love one another right now.”

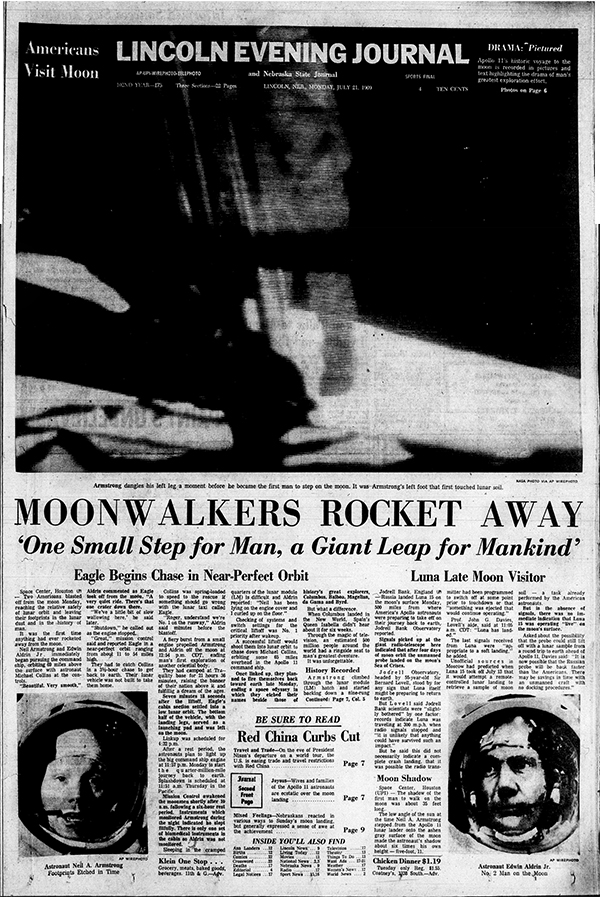

The “petty bickering, the jealousies, the hatreds among human beings and their sovereigns suddenly appear in all their pettiness when viewed against a moon that now has been visited by their representatives,” said the Lincoln Evening Journal. The editors hoped that the astronauts “somehow might inspire all humans to a deeper dedication to the performance of their own paramount function of living together in harmony.”

********************************