Omaha police officer James MacDonald spent a decade with one leg literally in the grave.

Few people visit their own grave—especially not when part of their body already lies buried beneath the headstone. But Omaha police captain James MacDonald was such a man.

In the early morning hours of December 21, 1921, MacDonald and several other patrolmen responded to a call that safecrackers were looting a grocery store at 40th and Dodge. The safecrackers—or “yeggmen” in the slang of the day—were attempting to blow open a safe with nitroglycerine.

MacDonald’s police car had barely pulled up when the burglars opened fire.

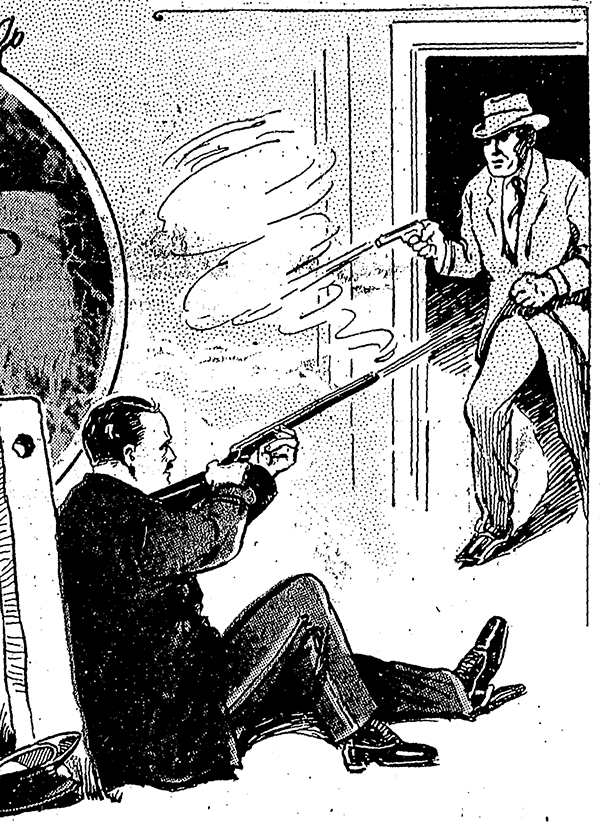

“MacDonald had scarcely stepped to the sidewalk… when a shot from the lookout’s gun shattered his left ankle and the bone clear to the knee,” the Omaha World-Herald reported in a December 30, 1928, retrospective. “He slipped to the pavement and, sitting with his back to a hitching post, continued the assault with the shotgun he carried, from this position. Here started a battle in which it has been declared more than one hundred shots were fired—a fray lasting nearly half an hour, and heard by neighbors for blocks around.”

Illustration (and photo at top of page): Omaha World-Herald, Dec. 30, 1928.

As the bandits tried to shoot their way out of the drug store, MacDonald drove them back inside with his shotgun. Another bullet struck him in the left knee. The World-Herald continues:

“‘You got me again!’ Jim called, and fired back, the shot striking the man’s hand, knocking down his pistol. Checks and securities, which were wrapped around the handle of the automatic, fell to the floor covered with blood. ‘You got me too,’ replied the bandit.”

Did they really say that, or that a bit of storyteller’s license? The original 1921 reports don’t include this particular detail about the men politely informing each other about the results of their marksmanship. On the other hand, each man may have been trying to lure his adversary to come closer. Or they may simply have been in shock.

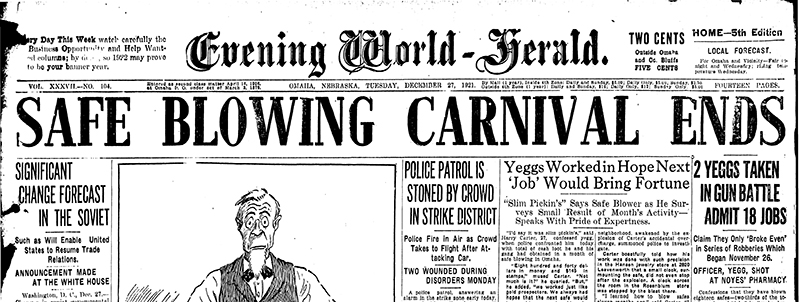

One of the burglars threw a bottle of nitroglycerine, but it failed to explode. Finally, “Jammed weapons and lack of ammunition forced the cracksmen to surrender.” The three men were arrested. They’d been blowing safes all over Omaha for weeks, but claimed they’d barely broken even due to the high cost of explosives.

Omaha World-Herald, Dec. 27, 1921.

MacDonald survived, but had to have his left leg amputated above the knee. While he lay in the hospital, his wife, mother, and two sisters took his leg to the cemetery for burial in a child-sized casket transported to the grave by a hearse. MacDonald later returned to the police force and retired in about 1923 with a captain’s pension.

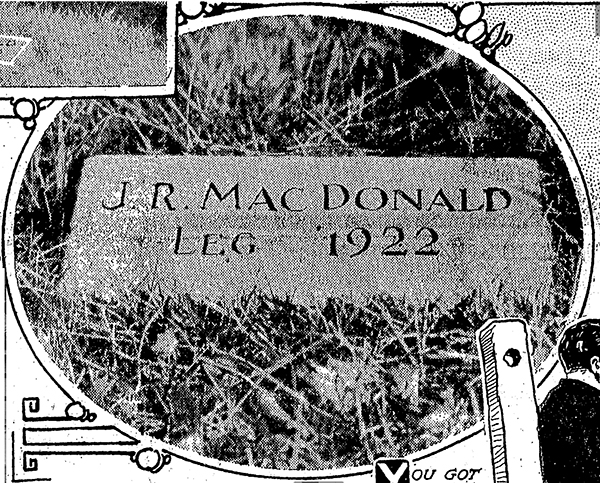

The 1928 article noted that MacDonald now “gets about right well” using only a cane. Each Memorial Day he went to the cemetery to place flowers on the grave where his leg was buried under a headstone that read, “J. R. MacDonald / Leg 1922.”

“It’s a kind of queer feeling to stand by the side of your grave—to know that part of you is standing above ground active and well, and the rest of you, your body, I mean, lies below, dead and buried,” MacDonald said. “But it was a good leg; it served me for many years, and I’m not going to forget it.”

Though the 1928 story is whimsical, the leg burial had a serious point behind it. The family was apparently celebrating the fact that they didn’t have to bury the rest of their husband and father. A week after the 1921 shootout, the World-Herald had run an editorial titled “The Police Problem,” in which it observed that “a policeman’s lot is not a happy one,” and a that a patrolman “takes his life in hand to protect the community which pays him a very modest stipend to serve as the monitor of law and order.”

The rest of James McDonald joined his missing leg at Westlawn-Hillcrest Memorial Park after his death in 1932. The “Leg” headstone was replaced with a more conventional one with the inscription: “He fought a good fight.”