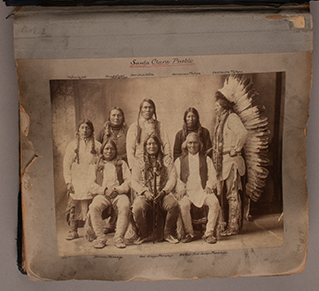

The Paper Lab at the Gerald Ford Conservation Center recently completed the treatment of four photograph albums from the Omaha Public Library collection. They depict many of the approximately 500 participants in the 1898 Indian Congress that was held in tandem with Omaha’s famous Trans-Mississippi Exposition.

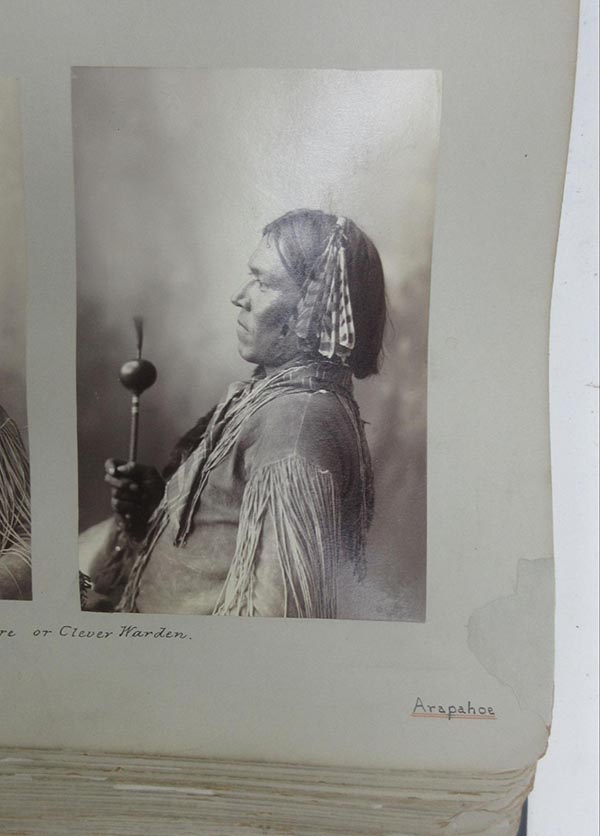

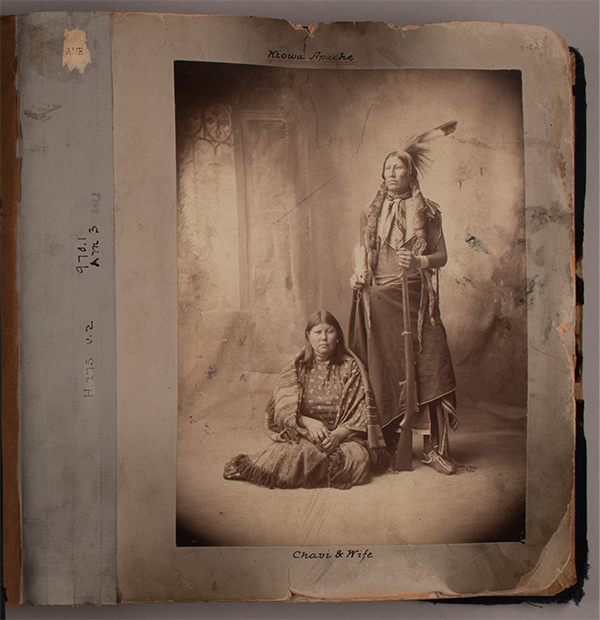

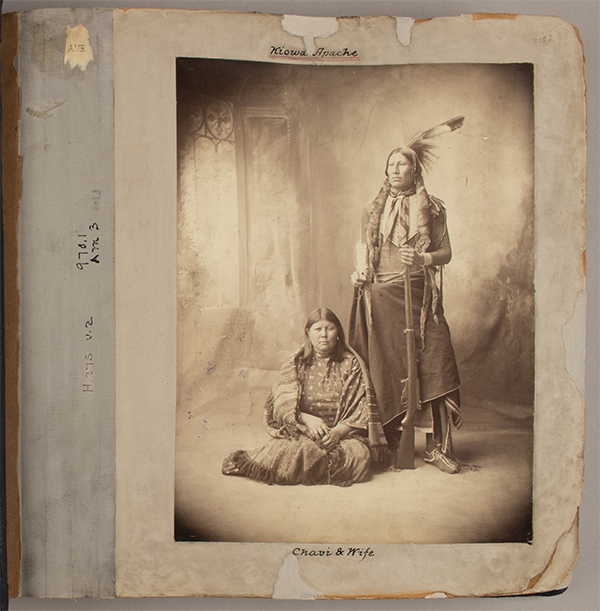

Frank Rinehart, the official photographer of the Exposition, took several hundred photographs of members of 35 Indigenous tribes in his studio on the Exposition grounds. Today, this collection constitutes one of the most important early 20th-century collections documenting Native American leaders and tribe members.

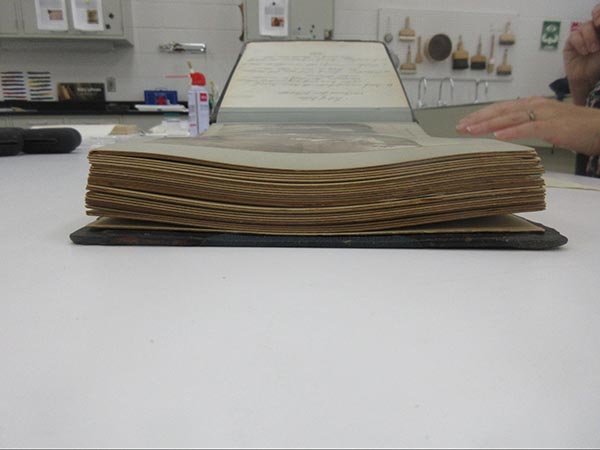

These volumes hold original prints of Rinehart’s portraits, but their condition made them difficult to access. The album pages are made of a thick, heavyweight pressboard that is naturally highly acidic. Over time, the acids in the boards had contributed to their discoloration and brittleness. Additionally, the pages of the volumes had become warped. This combination led to numerous cracks and material losses along the edges of pages.

From this angle, you can clearly see the warping of the album pages. While it didn’t have much effect on the photographs themselves, the warping weakened the boards, contributing to increased damage to the pages as the books were used.

At some point, a fire near where these books were stored left many pages covered in a fine layer of soot. The heaviest accumulations were concentrated on the first and last few pages of each volume and the book gutter where the pages of the book meet.

This page represents the damage found near the front of each volume. In addition to the dark soot marks, there are several cracks in the border and a large loss.

The main goal of treating these books was to stabilize their structure to prevent future damage. Where losses were present, paper fills were made; however, aesthetic issues were given less priority. This was due to the extensive time commitment that would have been necessary to match the tonal variation of each page, which had become a slightly different color over time.

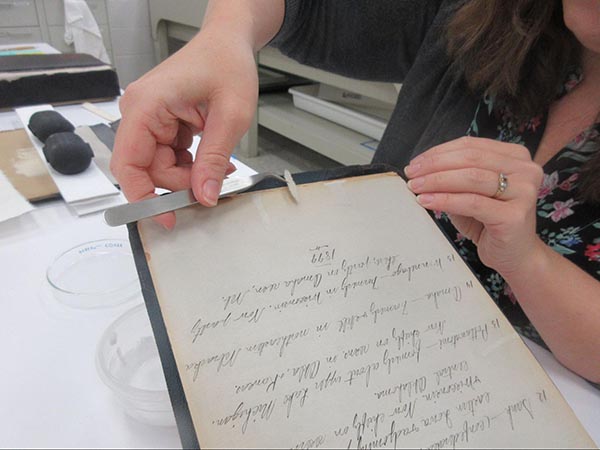

Dry cleaning methods were used to remove soot residue and other accumulated dust and grime from each page. Larger accretions were removed mechanically. Once this was done, a leather consolidant was applied to each leather book cover to protect against further wear and loss to the leather finish. Then, page by page, fragile edges were reinforced with adhesives and lightly toned reversible Japanese paper fills. Depending upon the damage, a paper fill can either simply hold a crack closed or replace a large section that has been lost. In both cases, the main goal is to help stabilize the page and prevent aggravating any damage.

Paper conservator Hilary LeFevere places a small Japanese paper fill over a crack on the edge of a page.

An example of a larger paper fill used to repair a loss that could easily lead to additional damage.

The covers of each book also had various condition issues, with both detached and loose covers. These were reattached and reinforced.

Paper conservator Hilary LeFevere uses a bone folder to flatten material, attaching a book’s cover to its spine. The larger volumes had a unique metal structure that allowed the spine to be expanded to fit additional pages.

While the books are now much more stable and safe to handle, this project also included the complete digitization of each book. Having digital reproductions of each of these images will help limit the need to handle the books in the future, which will, in turn, reduce the risk of additional damage.

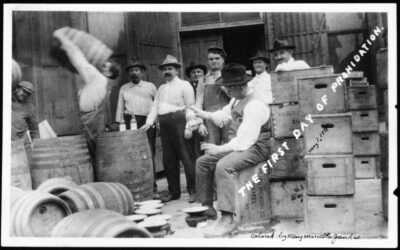

Before-treatment photograph of the first page in one of the volumes.

After-treatment photograph of the same page.