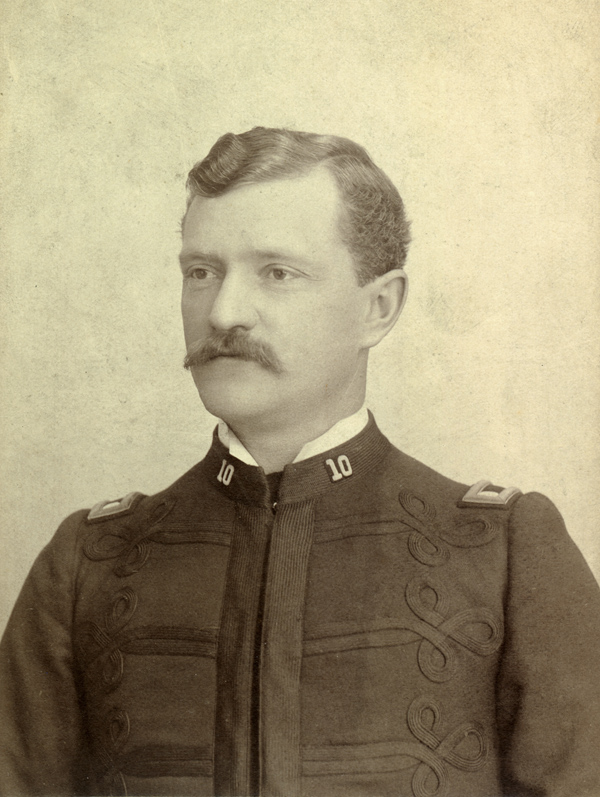

George D. Meiklejohn, as a U.S. congressman representing Nebraska’s Third District, 1893-97. RG2411-4975

As a result of the Spanish-American war of 1898, the United States was suddenly a colonial power, untested in the administration of overseas territory. George Meiklejohn, Charles Magoon, and John J. Pershing were three men who had seen the “taming” of the American frontier, and as they rose to national power they applied what they had experienced in the Midwest to colonies abroad. In the Winter 2014 issue of Nebraska History, Katharine Bjork explains how these three friends with roots in Nebraska had a lasting impact on U.S. colonial policy.

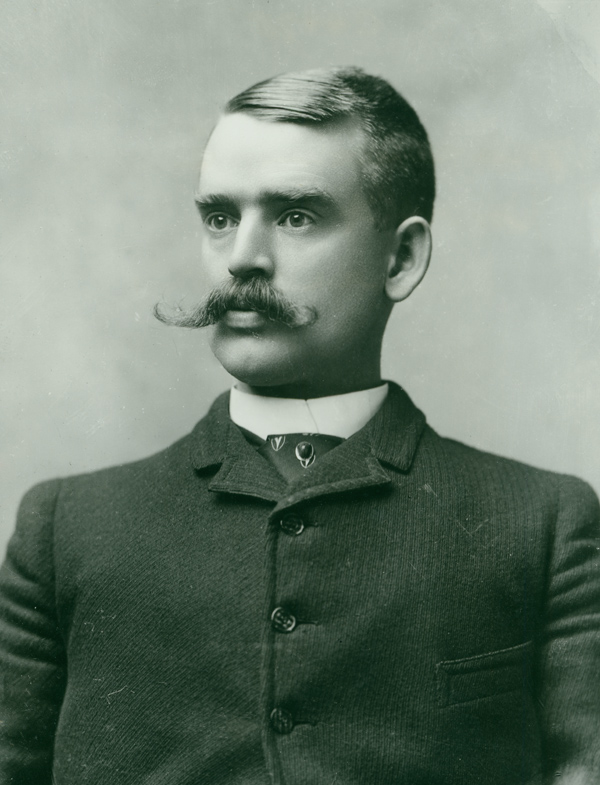

The three friends had relatively successful careers in Nebraska: Meiklejohn as a congressman, Magoon as a lawyer, and Pershing as a military instructor at the University. But the friends’ rise to prominence was only just beginning with Meiklejohn’s appointment as Assistant Secretary of War in 1897.

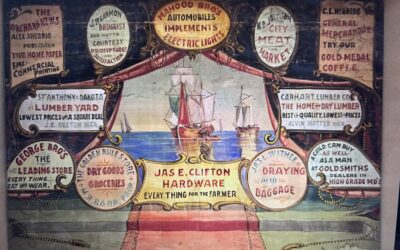

The U.S. was emerging as a world power. In 1898, Congress approved involvement in Cuba’s rebellion against the Spanish, sparking the Spanish-American War. At the end of the conflict, the U.S. gained control over Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. Meiklejohn, Magoon, and Pershing took an interest in these international affairs. Policies that had been tested on the Midwest, such as the Homestead Act, helped shape how these men believed territory should be organized. With Meiklejohn’s help, they were soon in positions where they could implement those visions.

Meiklejohn used his power in the War Department liberally. The Secretary of War who was supposed to oversee him, Russell Alger, was frequently sick or absent. When Alger was gone, Meiklejohn became the Acting Secretary of War. On one such occasion, Meiklejohn used his authority as acting secretary to send a directive to himself as assistant secretary, ordering himself to “take charge of all matters relating to customs duties to be levied and collected in Cuba, Porto Rico (sic) and the Philippines.” He willingly accepted the orders from himself, and began to handle all incoming insular matters.

John Pershing preferred field work over administration. More than once he wrote to Meiklejohn requesting particular positions that would allow him to stay abroad with the military, first in Cuba and later in the Philippines. In both places he held influential positions, including military governor of a Philippine province for several years

Charles Magoon’s role in overseas affairs mirrored his Nebraska law experience, but on a much grander stage. As Bjork writes: “As law officer for the Bureau of Insular Affairs, one of Magoon’s main tasks was to survey the entire body of civil law pertaining to the formerly Spanish colonies to make recommendations as to what should be retained and what adapted.” In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Magoon as the provisional governor of Cuba, charged with maintaining stability and protecting U.S. interests in the aftermath of a fraudulent election.

Together, George Meiklejohn, Charles Magoon, and John J. Pershing had a substantial amount of power. They entered U.S. colonial policy when it was still being developed, and had the opportunity to implement ideas that would remain for generations.

– Joy Carey, Editorial Assistant, Publications