A delicately detailed doll named “Lucy” has been in the History Nebraska collection since the mid-1900s. She originally belonged to a woman named Ida Epley Davis, who moved with her family to Omaha by covered wagon in the 1880s.

According to popular legend, this particular type of doll, typically called a “milliner’s model,” was used as a mini mannequin to display new styles in shops. This idea, however, has been largely dismissed by historians. These dolls were extremely popular among both children and adults in the early 1800s through the beginning of the 20th century.

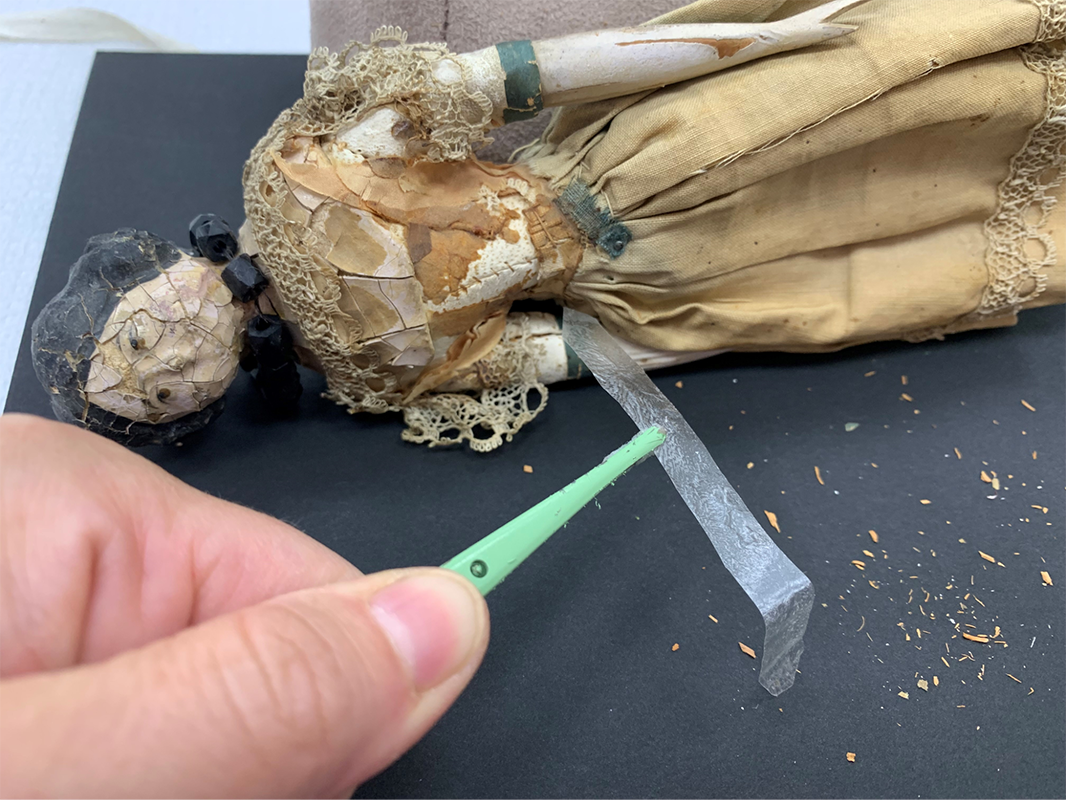

Typically made of painted papier-mâché or wood, leather bodies stuffed with sawdust, and minutely-detailed clothing, these small dolls provide a reflection of contemporary fashion, and “Lucy” is no exception. Her clothing is made of cotton and silk, and her bodice and bloomers are trimmed with ornate lace. However, when she arrived in the Ford Conservation Center’s Objects lab, both her underlying structure and clothing had seen heavy deterioration from handling and aging of materials over almost 200 years.

The silk bodice on Lucy’s dress was shattering, and much of the fabric had been lost. The thick painted varnish on her face and limbs was detaching from the papier-mâché below. The kid leather on her upper arms and bodice was tearing, resulting in loss of sawdust stuffing every time she was moved.

In this image, you can see that Lucy’s cotton dress was faded, stained, and developing splits along creased pleats. The skirt was originally blue and the bodice much darker; sections of this color remain on the back side of the doll, which had been more protected from light exposure.

Lucy’s treatment posed some challenges, as there were many different problems involving a variety of media. The first step of treatment (after documentation) is often testing, which provides a framework for an object’s tolerances to intervention. During testing, it was found that the black paint on her hair was unvarnished and sensitive to most solvents, including water, which limited what could be done without causing additional damage. The painted face, neck, and wooden limbs, however, appeared to have remnants of a varnish layer that helped to protect the paint below during the process of grime reduction.

After testing, the lifting and flaking paint on her face and chest was consolidated to prevent additional losses during and after treatment. Her arms were loose, and slight movements resulted in sawdust filling coming out through the joints. These were stabilized, and a large crack in her foot was also repaired. Then, surface grime was reduced using dry methods and appropriate solvents on the face, neck, and limbs.

So much of Lucy’s bodice was missing that a bit of research was required to be able to inform whether it could be accurately reconstructed. Several images of milliner’s dolls from the same era with similar necklines were found. These images, and hints from the lace trim that remained intact, provided enough information to reconstruct a layered organza bodice that stabilizes the shattered silk while at the same time minimizing the damaged appearance. The original fabric was retained in place, and is visible under the layers of sheer organza. The splitting creases in the cotton skirt were stabilized from the inside.

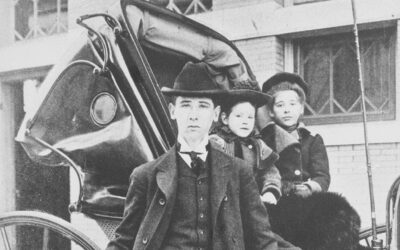

Object conservator Rebecca Cashman prepares to place a strip of clear goldbeater’s skin inside Lucy’s skirt along one of the long splits.

Finally, the most distracting cracks and losses on Lucy’s face and arms were filled with a reversible media and toned to match the surrounding material.

After filling and toning, the cracks and losses on Lucy’s face are less distracting. Her new bodice is made of layered organza that matched the dark spot on the back of her bodice, as this is likely closer to the original color.

Following treatment, Lucy is in stable condition and can be handled, stored, and exhibited without causing further loss of original materials. Though her age and all she’s been through can be seen when examined up close, her overall appearance is much closer to what it was when she made her journey to Omaha by covered wagon.

Lucy before and after stabilization and some aesthetic compensation.

Toward the end of her life, Mrs. Epley Davis gifted Lucy to Dr. Olga Statsny, a prominent doctor in Omaha. It’s unclear whether Mrs. Davis and Dr. Statnsy knew one another well, but Dr. Statsny was well-traveled and a collector of dolls from around the world. Her collection at History Nebraska includes almost 30 antique dolls from a variety of cultures and traditions. A note from Mrs. Davis (likely addressed to Dr. Statsny) accompanied the doll all the way to History NE:

“Our family are all from Ohio, including Lucy. My grandmother was a member of an Ohio pioneer family, making Lucy far over one hundred years old, from grandmother she was handed down to Mother, and then to me. She was always to be looked at and not played with. I will miss Lucy but I am also so please [sic] to know she is in good care, hope you will be pleased with her, she does not cause much trouble. I might call and see her sometime, I have no one to give her too [sic] as I am entirely alone. Yours, Mrs. Ida Epley Davis, 4644 Douglas St.” [Omaha].