Seventy-five years ago, the USS Missouri was the site of the surrender of the Empire of Japan to Allied Forces, ending World War II. The signing of the surrender took place on the deck of the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945. The Missouri was the last battleship commissioned by the United States and had been christened at her launching by Mary Margaret Truman, daughter of Harry S. Truman, then a United States Senator from Missouri.

After seeing duty in WWII, Korea, and the Persian Gulf, the ship was donated in 1998 to the USS Missouri Memorial Association and became a museum ship at Pearl Harbor.

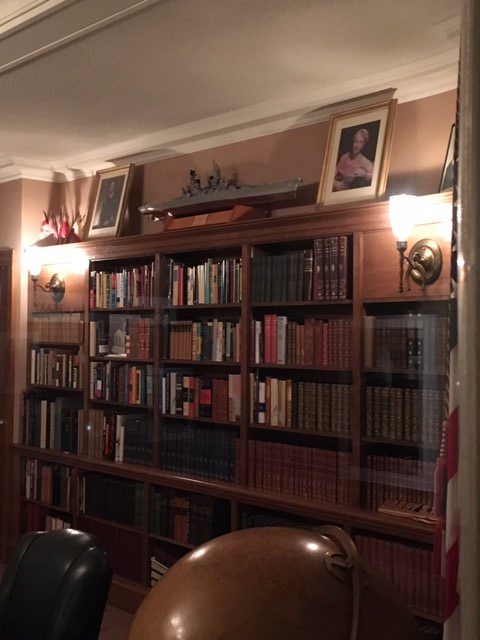

The USS Missouri model on exhibit at the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum in Independence, MO.

The model shown here belongs to the Harry S Truman Library and Museum. According to Clay Bauske, curator at the Truman Library:

The model was made by David Beauchamp of San Francisco. (We do not have any additional information about Mr. Beauchamp.) He presented it to the Truman Library on September 20, 1957 (less than three months after the Library first opened). Former President Truman chose to display it in his office here, and it’s been on display there ever since. Truman worked in his office here 5 to 6 days a week, and, in the early days, he was often the only person here on Saturday mornings (except for a couple of security guards). A few years after Mr. Truman’s death in 1972, his office was made available for viewing by the general public.

The overall image of the ship before treatment.

The ship model is built mostly using balsa wood, though some elements, like the propellers and the hoist, are made of cast iron alloy. The ship is decorated with different colors of paint, and the wood of the deck is stained tan. The multiple gun turrets are attached to the deck via snap fittings on their bases, allowing them to be swiveled around. A string railing is attached to a series of small iron alloy finishing nails around the perimeter of the deck. Anchor chains are made of a thin copper-alloy chain and black thread makes up the rigging. Small United States paper flags hang on the rigging and a small U.S. Navy Jack flag, blue with white stars, is at the bow of the ship.

When it came to the Ford Center, the model was in good condition overall. Some of the small pieces had broken off from their original positions, and the rigging had become detached in a few places.

Detail of the ship model before treatment. You can see the visible dirt on the surface as well as the broken rigging threads.

Most obvious was a thick layer of surface dirt from the lack of cleaning and dusting over the last thirty years.

The model was scheduled to go on permanent exhibit and needed to be in ship-shape.

Detail of the ship during treatment. You can see the deck on the left has not been cleaned.

The flaking decals were consolidated and then it was time to swab the decks. Literally. Cotton swabs were used with saliva to clean every surface on the ship model. It took ten hours to clear the dirt and grime from every nook and cranny.

Conservation Technician Megan Griffiths, spent ten hours swabbing the decks of the USS Missouri.

Once the model was clean, the broken components could be reattached and the losses filled and toned to match the surrounding areas. Ultrathin hair silk was used to repair the black thread used for the model’s rigging.

Detail of the ship after treatment. The rigging has been repaired, and the surfaces cleaned.

Replacements were made for the three missing guardrail posts by removing the heads from ½” long stainless steel pins secured in the vacant holes. And hair silk was used again to secure the guard rail.

Unsure of the original position of the two-legged hoist support, it was determined by viewing the deck of the ship using a long wave ultraviolet lamp and noting the areas where the top layer of varnish was absent from the decking.

The overall image of the ship model after treatment.