World War I killed some 15 to 19 million people, but the 1918 flu pandemic was far worse. As the flu raged around the world, Nebraska communities responded.

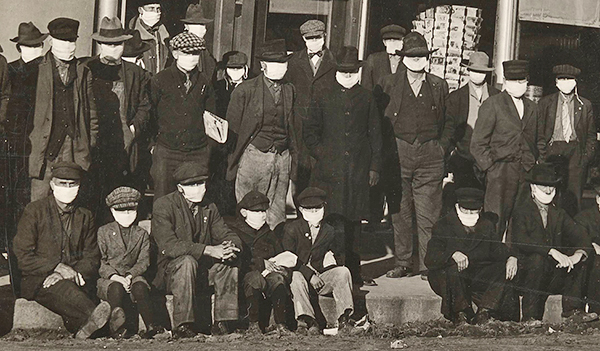

Photo: Men wearing surgical masks in Shelby, Nebraska, December 8, 1918. History Nebraska RG2017.PH

A new and deadly flu strain hit the US early in 1918 and greatly intensified by September. It was part of a global pandemic. How did Nebraskans respond?

The “Spanish Flu”

People called it the Spanish Flu because of its supposed place of origin. Symptoms included high fever, cough, dizziness, and heavy perspiration. Frequently bronchial pneumonia developed, with death following in a high percentage of such cases. This strain of flu was unusual in that it was deadliest to healthy young adults.

The virus had been spreading for months, but the growing number of cases was underreported due to wartime censorship. During World War I the United States and many other countries censored bad news so as not to encourage their enemies. Later it was found that the so-called Spanish Flu didn’t originate in Spain. It’s just that Spain was neutral in the war and didn’t censor press reports of the illness.

The flu reached Nebraska by October. Red Cloud reported two flu deaths on October 2. Omaha reported its first case the next day. Scottsbluff reported its first cases on the 15th.

Closings and Quarantines

On October 7 the state ordered the closing of all “schools, churches, places of entertainment or public congregation, pool halls and other places of amusement.” Mail carriers continued on their rounds, but wore white face masks for protection.

Quarantine rules were issued for affected homes. All residents of a house who had been in contact with a diseased person had to remain in the house until the quarantine was lifted. Only a doctor or nurse was permitted to enter or leave the house while the quarantine was in effect, though medical professionals were in short supply. Necessary supplies could be brought to the house and left outside the door. Soiled clothes could be sent to the laundry if placed in a package covered with paper.

In a 2015 doctoral dissertation for the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Kristin Watkins examined the history of the pandemic in selected smaller Nebraska communities (Wayne, Red Cloud, Anselmo, Valentine, Scottsbluff, and Gering) and surrounding rural areas.

“It is clear that rural location did not provide protection from the virus,” Watkins writes. One lesson, she concluded, was that rural communities should not be lulled into a false sense of security by their geographical isolation.

In 1918 many Nebraska communities were still relatively new. In some, a lack of “basic services like supportive health care may have led to more deaths in counties lacking infrastructure such as hospitals, as was the case in both Cherry and Scottsbluff counties.”

In Lincoln and Omaha, “crowding and travel, as well as non-compliance with the ban on public gatherings, allowed the disease to reach out-of-control proportions. In rural areas, the motivators of community action were different, and non-compliance usually entailed local politicians trying to break quarantine to pursue their campaigns, with residents protesting and sticking to the quarantine.” To the extent that communities used them, measures such as “social distancing” and quarantines seemed to reduce the spread of the virus.

Medical treatment was primitive by today’s standards. There were no flu vaccines or antiviral medications, no antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections. Even the flu virus itself was as yet undiscovered by science.

War Ends, Santa Arrested

The statewide ban on public gatherings was lifted on November 1, but the flu continued. An armistice ended World War I on November 11, but victory celebrations were limited in many towns. Valentine, for example, didn’t lift its local ban on public gatherings until November 29, and the University of Nebraska did not resume classes until after Thanksgiving.

There was almost nothing of a holiday season that year. No Christmas events or entertainments were held, and Nebraska merchants sustained severe losses from the slump in trade during the last six weeks of the year. In Gering, a department store arranged for a visit by Santa Claus on December 2—but hundreds of children were shocked when police arrested both Santa and the store owner for violating a local ban.

Nationwide, the epidemic was still claiming thousands of victims by mid-January 1919, but in Nebraska the worst was over.

Omaha alone saw 974 deaths between October 5 and December 31. The state’s overall death toll was variously reported between 2,800 to 7,500 people—a broad range because Nebraska’s reporting was so woefully incomplete. Medical professionals gave various reasons for this. Many said that the large number of patients left them little time to keep good records. Federal officials considered Nebraska’s numbers so inaccurate that they omitted them when calculating the nation’s total infection rate and mortality.

Globally, World War I killed 15 to 19 million people, military and civilian (including 751 Nebraska soldiers). The influenza pandemic proved far deadlier, taking somewhere between 50 and 100 million human lives.

Read on: Omaha Bankers Asked: Does Money Spread the Flu?

Adapted from “Flu Epidemic, 1918,” Nebraska Timeline column, Nebraska State Historical Society (aka History Nebraska), November 1999.

Additional sources:

Kristin A. Watkins, “It Came Across the Plains: The 1918 Influenza Pandemic in Rural Nebraska,” PhD. Diss., University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, 2015.

“The 1918 Flu Pandemic: Why It Matters 100 Years Later,” Public Health Matters Blog, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 14, 2018. https://blogs.cdc.gov/publichealthmatters/2018/05/1918-flu/